SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

It was a Friday morning, February 17, 2006. Children were in school and parents were going about their daily chores. Suddenly, the mountain slope overlooking their village collapsed, burying many villagers alive in thick, slick mud.

In just about two minutes, a whole community was lost. The collapsed portion of the mountain took 1,500 lives.

There were signs. In a way, nature was trying to communicate little warnings days before the tragedy struck. In hindsight, experts say, many would have lived if people learned to read the signs and acted on them.

Here is a timeline of what happened on that tragic day:

December 2005 – Some residents start to notice the tilting of trees, and the appearance of springs that are not usually there.

February 1, 2006– Heavy rains of 4 to 5 times the normal amount that used to fall on the area poured along the mountain slopes. This goes on for the next two weeks.

February 15 – After two weeks, the incessant rain subsides. Residents start returning to their houses.

February 16 – Aside from the small springs seen two months before, small rocks from the top of the mountain start falling from time to time, according to some residents.

February 17, around 10:30 am – An earthquake of magnitude 2.6 occurs 21 kilometers near Guinsaugon village. Almost simultaneously, a massive landslide occurs on the mountain slope facing Guinsaugon, carrying with it 1.2 billion cubic meters of mud and boulders up to about 3 kilometers. Minutes after the landslide, rescue efforts start.

February 25 – Southern Leyte Governor Rosette Yñiguez Lerias announces that they are calling off rescue efforts. Only 137 bodies and 15 body parts have been recovered, while 937 people remained missing – all presumed dead.

What went wrong?

The building of Guinsaugon village, as well as the other villages located along the footslopes of the Mount Can-abag was a disaster waiting to happen.

“The land where the houses were built were old landslide deposits,” Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB) senior science research specialist Salvio Laserna said. “Maaring nagkaroon na ng malalaking landslides doon noong wala pang tao.” (It’s possible that big landslides had occurred in that place before the place became inhabited.)

Laserna explained that old tension cracks, scars, and cat-like scratches on the surface of the mountain indicate that there had been major landslides before.

He also said that, prior to the disaster, MGB had been giving advisories to local government units that those communities were very prone to landslides since they were located at the footslopes of the mountain.

“’Yun ang problema kasi namin eh, wala kaming police power para paalisin ‘yung mga tao. kami ay sa recommendation lang,” Laserna said. (That’s our problem. We don’t have the police power to force people to leave. We can only recommend.)

The top of the mountain, according to Laserna, is also full of gullies – small channels along the mountain slope where water passess through and where landslides start to develop.

Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) Director Renato Solidum said the mountain’s proximity to the Philippine Fault Zone also adds to its vulnerability to landslides.

“If there are earthquakes, [mountain] slopes can be [easily] fractured. So, essentially, the [mountain] slope [facing Guinsaugon] was already fractured. Maraming bitak.”

According to Malyn Tumonong, senior science research specialist at MGB and spokesperson for the team of geologists that the bureau sent to St Bernard, rocks that made up the mountain overlooking the village were shattered when the Philippine Fault—which runs from Luzon to Mindanao—cut across Leyte Island around 5 million years ago.

This made the rocks prone to weathering, erosion, and alteration. Movements in the fault zone also caused the rocks to continuously grind against each other, pulverizing them in the process.

Observe nature, communicate warning signs

The signs that were already visible days, even months, prior to the big landslide could have saved lives, Solidum said.

As early as two months before the disaster, some people familiar with the mountain had been noticing significant changes, such as tilting of the trees and appearance of springs, not normally seen in certain parts of the mountain.

Signs as such have significant meanings. Normally, rainwater seeps through the soil, depending on the original layers. If there is ground movement, the original path of the water becomes disrupted and so it has to find another opening, which is through the cracks formed from such movement, according to Solidum.

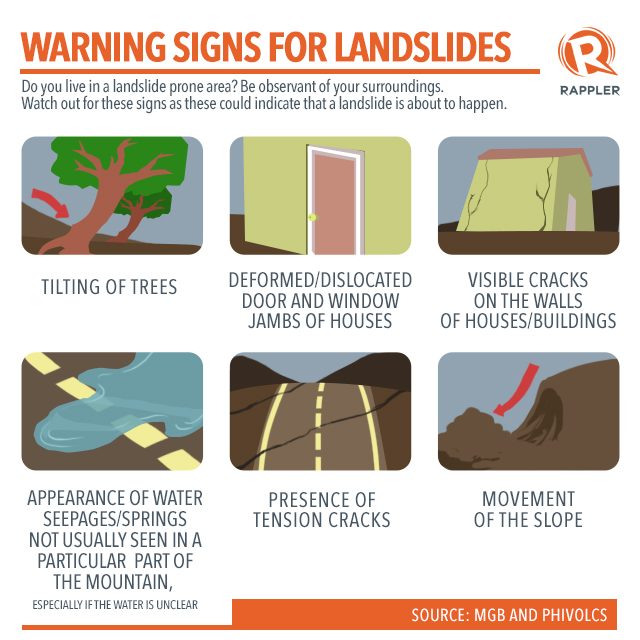

Other signs of ground movements according to MGB and Phivolcs are:

Had the information been shared, residents would have been more prepared.

“People see but they don’t share the information. I think communities need to have a good network among the residents especially those [who] frequently [go to the] slopes. [Once they notice changes], they should report to the barangay official,” Solidum said.

Climate change and landslides

“I use Guinsaugon landslide as an example of a condition that would happen during climate change – global warming,” Solidum said.

As the years go by, the effects of climate change become more and more evident all over the world. In the Philippines, whose location along the typhoon belt and the Pacific Ocean’s Ring of Fire exposes it to major hazards, its effects could be much worse.

Landslides can be triggered by rain or earthquake alone, “but if you have a combination, then it is easier for landslides to happen,” Solidum explained.

Solidum says it is important to look at how climate change could exacerbate the effects of natural hazards. As the world gets warmer, the more evaporation happens, thus more rain forms. Frequent and more intense rainfall will make the mountain slopes wetter, making it easier for landslides to occur.

With the country being seismically active, earthquakes could occur and aggravate the situation.

It is also important for people to be familiar with the different types of landslides that could occur. What happened in Guinsaugon, for instance, was a deep-seated landslide, according to Solidum.

Deep-seated landslides are those which do not occur immediately during a heavy rain. “There’s a lag time [during which] the water would have to pass through and seep in through the soil, and then at some point it gets saturated,” Solidum said. But because of the earthquake, it became sooner.

“[Yung landslide ay] para bang buntis na nanganak na kahit hindi pa due,” Solidum added. (The landslide was like a pregnant woman who gave birth prematurely.)

Using hazard maps

Had there been detailed geohazard maps before, the damage caused by the landslide would have been minimized and the loss of life could have been prevented.

While MGB had started its geohazard mapping way before the tragic event, it is only recently that government agencies are able to actually produce hazard maps.

In 2010, MGB was able to complete 1:50,000 scale rain-induced landslide hazard maps for the whole country. Higher resolution maps at a scale of 1:10:000 are already around 85% complete.

Meanwhile, Phivolcs, the agency in charge of producing earthquake-induced hazard maps, has been granted by the Department of Science and Technology a program called the “Development and Deployment of Early Warning System for Deep-seated Catastrophic Landslides and Slope Failures.” It will allow them to place sensors in slopes that have a potential of being affected by deep-seated landslides.

The University of the Philippines (UP) National Institute of Geological Sciences and the UP Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineering are also part of the project.

So far there are 11 sites in Benguet, Surigao del Sur, Negros Oriental, Iloilo, and Southern Leyte where these sensors have been installed.

But disaster prevention and mitigation does not end with mapping and understanding the hazards.

Now that the maps are available, the next challenge is for communities to use them for development planning and coordinated action to make sure that disasters like the one that happened in Guinsaugon will never happen again. – Rappler.com

Sources: Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Mines and Geosciences Bureau, various news websites

Editor’s Note:

February 17, 2015, is the 11th anniversary of the landslide that practically wiped out the village of Guinsaugon in Saint Bernard, Southern Leyte. This series on Rappler digs into what happened, what have been done since, and what can communities do to prevent future tragedies.

This series is part of Project Agos, a collaborative platform that combines top-down government action with bottom-up civic engagement to help communities learn about climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction.

Project Agos harnesses technology and social media to ensure critical information flows to those who need it before, during, and after a disaster. It is a partnership between Move.PH, Rappler’s civic engagement unit, and agencies such as the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS), the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB), the Office of Civil Defense, the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) and other key stakeholders.

Project Agos is supported by the Australian Government.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.