SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

At around 4 pm on that fateful afternoon of July 16, 1990, I was doing my post-table tennis practice ritual – puffing my Marlboro Reds near the Inang Laya statue inside the UP College Baguio campus while watching the women’s volleyball team wrap up their scrimmage at the court below.

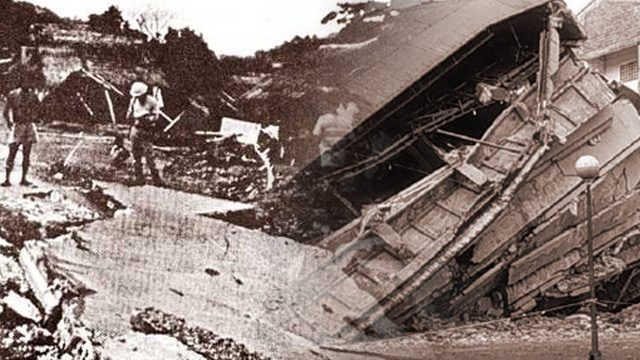

Suddenly, I heard a loud rumble from the ground followed immediately by a tremendous jolt that almost knocked me off my feet. As I struggled to keep myself standing, I saw fellow students rushing out from the 20s classrooms. The brick wall in front of the Secretary’s Office started to fall apart. The resonating sound from deep under muted the screams of the students. That was when I realized it was a powerful earthquake.

Instinctively, I ran towards the open space in front of the Oblation. When the violent shaking stopped, I found myself near the flagpole holding on to a fellow student. Another violent quake ensued making us once again disoriented and helpless. I remember someone shouting, telling us to veer away from the flagpole because it was wildly swaying.

When the earthquake was over, I wondered what might have happened with my table tennis racquet. I went looking for it at the SPEAR Hall, but when I arrived, the place was eerily deserted and wet; and my racquet was nowhere to be found.

Suddenly I came to my senses, something bad may have happened to the table tennis team. I felt guilty looking for my racquet first. I headed towards the archery range calling out their names. I saw the riprap beside the SPEAR Hall eroded by a seemingly large amount of water. I grew more concerned. I was relieved when I heard someone’s voice calling out to me from the archery range.

And then I saw the members of the team – Grace Santos, Carmela Claur, and George Ventura – emerge from the far corner near the Tourism Office, mud all over them, dazed, but unhurt. Gino Orticio, another member of the team, was in his history class with Professor Violeta Adorable. Someone handed me my racquet and started telling me why they looked liked victims of a mudslide.

‘Tidal wave’

It turned out that the water tank above the Spear Hall came down on its roof, creating a wide gash and spilling the water into the hall. They thought Baguio City was being submerged by a tidal wave caused by the earthquake. When someone shouted “Tidal wave!”, everybody rushed toward the door and ended up at the archery range.

After hearing their story, I couldn’t help but laugh.

That “tidal wave” story may have been a blessing in disguise and a comic relief. When we have composed ourselves, the devastation brought by the quake upon the city, the emotional distress slowly creeping upon us, and the task of sheperding the students stranded in the campus started sink in.

Shortly after dusk, the fog started to descend and engulf the surroundings of the campus. The silence was deafening in the next couple of hours. The atmosphere was surreal. Soon, the gruesome aftermath was punctuated by the sirens of ambulances wailing incessantly as victims were transported to nearby hospitals. Most of us sought shelter under the shaded walk and huddled close to friends.

In a manner of speaking, death was all around us.

In the evening, we started to relax and shared jokes over a bottle of Ginebra. I remember Hans Christian Tesch saying that the giant earthworms moving beneath the earth’s crust caused the earthquake.

We decided to camp in the campus in the first few days.

We were constantly moving from one place to another because of the 5-minute intervals of the aftershocks making us practically cover the whole campus (I was with Denden Alicias, Dominique Garen, Jefran Barraquio, and Anthony Denina. Denden was 8 months pregnant then with her first-born, a daughter they named “Quake”): near the auditorium, parking lot, freedom park, the Philippine Rabbit Bus parked in front of the entrance, and the shaded walk.

Isolated city

On July 19, 1990, I have already counted more than 200 aftershocks, the strongest happening in the early hours, and finally bringing down the Hilltop Hotel to the ground.

Agony was the operative word in the first 3 days after the earthquake. Baguio City was isolated from the rest of the country. All telephone lines were down. To make matters worse, there was no electricity, very little source of potable water, and food.

We never had earthquake preparedness and post-earthquake debriefing training, but there were students that needed to be emotionally strengthened and fed.

Dean Patricio Lazaro, Profossor Vicky Rico (her maiden name) and Jolan Rivera (the then Student Relations Officer), led the efforts to care and feed the students. Domel Evangelista and I, members of the UP police, UP Diliman Mountaineering Club led by Boy Siojo (the brother of Mio Siojo), the UP Vanguard Fraternity and Officers of the UP Baguio Corps, and so many others I could no longer remember, helped in sourcing water and food, boost morale of the community, and ensure the safety of the campus.

The water came from the drums in the toilets and from the rains. Rice, coffee, noodles, and eggs were bought from a storeowner in Kayang who had the habit of opening and closing his gates in a middle of a transaction every time an aftershock ensued. We could not complain because we were more fearful of the debris falling on us rather than the annoyance of having to fall in line so many times.

Added security was provided by the members of the Vanguard Fraternity and the Officers of the UP Baguio Corps as they performed a round-the-clock watch to secure the campus and ensure the safety of those encamped.

UP volunteers

In the latter part of the week, when the chaos, confusion, and the fear among us started wearing down, Gino Orticio and I volunteered for the Presidential Management Staff under the Regional Disaster Command. Gino was in charge with the computers while I operated the telephone lines of The Mansion House.

The relief goods were all centralized at the ballroom of the Mansion House. I was on the other hand stationed at the right side of the ballroom as you enter.

There were waterproof industrial grade flashlights and generators from Japan and thick blankets, noodles and Mah-Lings from China.

There was a time when I was already hungry but could not eat because the meeting of the barangay captains and the officials of Regional Disaster Center Command (RDCC) was ongoing. Volunteers were to eat only after the officials did.

In the meeting, they were deliberating on the effective distribution because the intended recipients were not getting the donated goods. Finally, they have arrived at a resolution, had their dinner, and I was able to eat, too.

However, they were unable to implement their resolutions as the industrial grade waterproof flashlights and generators started disappearing one-by-one and the thick blankets and the cans of Mah-Ling’s from China were magically turned into Iloko blankets and cans of sardines, all in less than 48 hours in the dark of the night.

After a week, we learned that airlifts to Manila were already available at the Loakan Airport. I decided to avail of the free service.

It took a few days more before we could eventually board a MAC-130 flight bound for Clark Air Base. Vic Jaleco, now the husband of the former Pen Banares (an UP Baguio alumna and now head of the Globe-Baguio City branch), graciously offered us his house as we wait for the next available flight.

Back to Baguio

Loakan Airport, like the rest of Baguio City, was a sorry sight of devastation.

People were blatantly ignoring common courtesy for the next airlift out of the city. Death could almost be tasted as the smell of formalin wafted in the air. Cadavers in body bags were left lying on the tarmac because there were not enough coffins for them.

Sadness and guilt overcame me realizing I was about to abandon a place I felt so loved and welcomed in such a forlorn state.

Nevertheless, in October, 3 months after the tragedy, I found myself in Marcos Highway, still perilous to negotiate because of the numerous landslides.

But I was oblivious. I was inside Anthony Denina’s Chevy Impala – the one we affectionately called the “Bat Mobile.” Anthony was on the wheel while Jefran Barraquio, Joan Virata, and I, were earnestly helping him to navigate the way.

We were on our way back to Baguio City. – Rappler.com

Nars Santos is an alumnus of the University of the Philippines Baguio (UPB) with a degree in Social Sciences. This article is part of a book of earthquake memoirs which was launched on July 16, 2015 in Baguio City.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.