SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Children should grow up to achieve their full potential, but for many Filipino children, this is not their reality.

Underfed and malnourished, millions of Filipino children go to school with empty stomachs – a barrier to their healthy development in their growing up years.

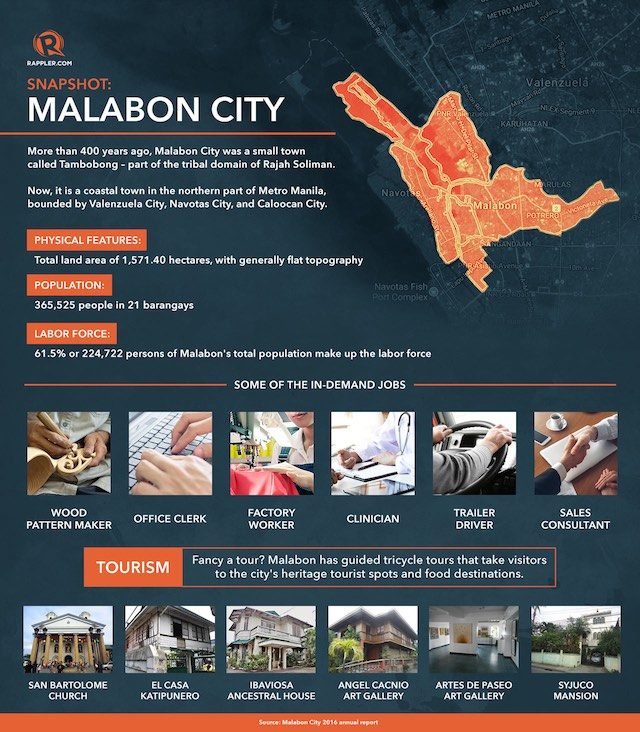

In Metro Manila, Malabon City has been waging a fight against hunger and malnutrition, and their efforts have been paying off in recent years.

From consistently ranking among the top areas in the capital region with high rates of malnutrition, Malabon has drastically cut its high rate of children who are stunted, severely wasted, or severely underweight.

For the city’s nutrition office, the goal is to make sure that Malabon kids are eating well, so that they grow up to be responsible and productive members of society.

One action being taken is the 90-day feeding program, an initiative that also brings in local businesses and the residents themselves in a community intervention effort.

Malnutrition rates

From 2012 to 2013, Malabon ranked second in Metro Manila areas with the highest rates of malnutrition, according to data from the National Nutrition Council’s Operation Timbang Plus (OPT).

But in a span of 3 years, stunting rates and other indicators of malnutrition have dropped for the city – an indication that the city’s interventions are reaping results.

As of 2016, Malabon has a total of 4,067 stunted children among 58,779 preschoolers included in the OPT survey. Of this number, 1,072 are classified as severely stunted.

For 2016, the city’s stunting rate is at 8.52% – a big drop from the 16.3% stunting rate recorded just 3 years ago in 2013.

| Estimated number of preschool children | 58,779 |

| Total number of preschool children measured | 47,717 |

| Normal | 42,318 |

| Stunted children | 2,995 |

| Severely stunted children | 1,072 |

| Total stunted children | 4,067 |

Based on 2016 data, 10 cities in Metro Manila were ranked among the top 100 cities and municipalities in the country with the highest number of stunting among preschool children.

Malabon City ranked 17th nationally, and 7th among Metro Manila cities.

Other indicators of malnutrition in Malabon also decreased over the years. The percentage of severely wasted kids is down to 3% in 2016 from 6% in 2013. The number of severely underweight kids went down to 3.17% in 2016 from 4.58% in 2013.

Community effort

The city has worked hard to bring its double-digit stunting rates down to single-digit figures, and it has tapped the communities to be involved in the fight against malnutrition.

The city’s 90-day feeding program is a cumulative effort among government officials, local businesses, and the residents themselves.

“We ask help from different business owners and private individuals to give us raw ingredients, so we ask for [something] as simple as sayote (chayote), ground pork, ground beef, saba (cardava banana), eggs. And then the city provides the rice, but a lot of the protein have been donated,” said city nutrition action officer Melissa Oreta.

Oreta uses her knowledge and skills as a professional chef in designing the menu, using the ingredients donated by the community.

“When I designed the menu, cost was the number one concern because we wanted to offer a meal at a lower cost but really healthy,” she said.

“We also cannot predict what the community will give us. Sometimes we’ll get canned goods, sometimes we will get a different kind of meat that we didn’t ask for, so we try to innovate from that and convert it into something healthy,” she added.

Oreta recalled how they had once received a donation of Hershey’s chocolate, and used that to make champorado (sweet chocolate rice porridge). A donation of macaroni ended up as macaroni soup, with vegetables and meat added to the mix to make it a healthier meal.

After implementing the program late last year in 5 barangays, there are currently 10 barangays and about 400 children taking part in the program.

Severely wasted or underweight children are given priority. This is determined after Oplan Timbang, where the city’s children are weighed and measured to identify those who are malnourished and should be given intervention.

Oreta said 90 days is the minimum period needed to rehabilitate children who are severely wasted or underweight. At the end of the 90-day program, children should have gained enough weight to be classified as “normal” upon graduation.

Changing mindsets

It’s already a challenge for the nutrition office to whip up healthy dishes from donated goods, but they have another battle to fight: the mindset that nutritious meals are costly and too bothersome to prepare.

Oreta said that money is usually not the issue. There are parents who just don’t prioritize nutrition enough to allot their budget for their kids’ healthy meals.

Because of this, some parents don’t bother sending their children to the 3 pm feeding program schedule, preferring instead to play tong-its or bingo.

“They have money to spare for other things, and yet they find it bothersome to take their child every 3 pm. It’s not like they don’t have cash to spend, there is [money]. That’s what we try to change when we give classes and when we talk to them,” Oreta said.

Over the course of the program, they also found that some parents considered the feeding program as a primary source of their children’s meals, rather than just a supplementary service.

City Mayor Antolin “Len-Len” Oreta III stressed that this should not be the case.

“They shouldn’t have their kids’ meals depend solely on the program. Many of them are like that, eating only during the program. They won’t eat at home. We want them to eat at home, to eat some more,” Mayor Oreta said.

‘We try to show them how proper nutrition will help them perform better in school.’

To address this, the nutrition office is incorporating lessons on parenting, values formation, and nutrition seminars to drive home the importance of healthy eating in the children’s growth and development.

Stunted growth, after all, affects a child’s cognitive development and overall health. But there are also repercussions on the national level: it costs the Philippines at least P328 billion every year due to losses in education and workforce productivity, according to non-governmental organization Save the Children.

With about 3.8 million stunted children in the country, this presents a worrying outlook for the country’s future.

“If you have the proper nutrition, then you’ll get sick less. We try to show them how it relates to [the children’s] developmental skills…how proper nutrition will help them perform better in school,” Melissa Oreta said.

To nip the problem in the bud, the city has included pregnant women in the feeding program, to help ensure healthier Malabonians right at the onset.

Sustaining momentum

What happens after the 90-day program is over?

To keep the children from slipping back to unhealthy habits, the city nutrition office designs the program to ensure that the meals can be easily recreated, using affordable and accessible ingredients.

Oreta said many parents have the misconception that healthy food means using expensive ingredients.

But she pointed out that this is usually not the case. The problem, she added, was not the cost, but the lack of knowledge on what healthy but affordable meals can be prepared.

This is why the nutrition office also integrates seminars and lessons to young mothers, who learn how to cook and keep a household with the help of their fellow resident mothers.

When done right, nutrition officer said the results at the end of the program are heartwarming: children who were once severely wasted and malnourished show up much healthier on graduation day. Some grew 3 inches in a matter of weeks, while one child even gained as much as 11 pounds.

One of Oreta’s favorite success stories was about one grandfather who took the effort to bring his grandchild to the feeding program every day without fail. The child ended up recording the most improvement in weight among that graduating batch.

“It’s nice every graduation day, because you see them at the start and then you see them after 90 days. You know that they’re healthier from the time that they’ve started. They’re more alert, they’re not lethargic….You see a big difference and I think every graduation makes it memorable,” she said.

Once the nutrition office finishes holding the 90-day feeding program in all 21 barangays, the cycle repeats again to include more children.

Ultimately, the city government wants to make sure that the new generation of children given these interventions will grow up to be responsible, capable, and dependable members of their families and of the larger society.

But Oreta knows that the long-term effects of the program will outlast local officials’ term in office.

“In the end, we want to create a generation of children who aren’t stunted…We would like them to be responsible citizens, and we feel that nutrition is a big part of it,” she said. – Rappler.com

The research for this case study was supported by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[WATCH] Killings continue in Camanava: 20-year-old slain in Malabon](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/09/tcard-2.png?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.