SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

ILOILO, Philippines – Malnutrition is not just about lack of food, but also the consequence of bad governance.

For instance, health facilities – even before Yolanda (Haiyan) hit last November 2013 – were already a problem. They are either old or few due to lack of funding. Post-disasters, the little equipment available are destroyed and not replaced. (READ: The road to poor health in PH)

“This prevents the early detection and treatment of malnourished children,” said Dr Martin Parreño, nutrition coordinator of Action Against Hunger (ACF), an international humanitarian organization.

“If each barangay had proper equipment, this could already save lots of money and lives,” Parreño pointed out.

Some health workers and volunteers also lack training, especially in malnutrition terminology and anthropometry, a tool for measuring malnutrition. Height boards and weighing scales are common, but MUAC (mid-upper arm circumference) tapes are less known. These are easy to bring and are used for screening malnourished children.

Barangay health workers (BHWs) – although classified as volunteers – are at the forefront of providing public health care, but they are not paid enough for all their hard work.

“Lack of budget” is an overused excuse, health advocates like Parreño protested. The real problem lies with wrong prioritization.

Where does the government put its money if not on the health and wellbeing of its people?

Malnutrition is everywhere

Malnutrition not only happens during emergencies, but it can happen any day and anywhere, even in progressive provinces like Iloilo.

Iloilo has the second highest rate of child malnutrition in the Western Visayas region, with more than 10,000 severely wasted children, according to the National Nutrition Council (NNC).

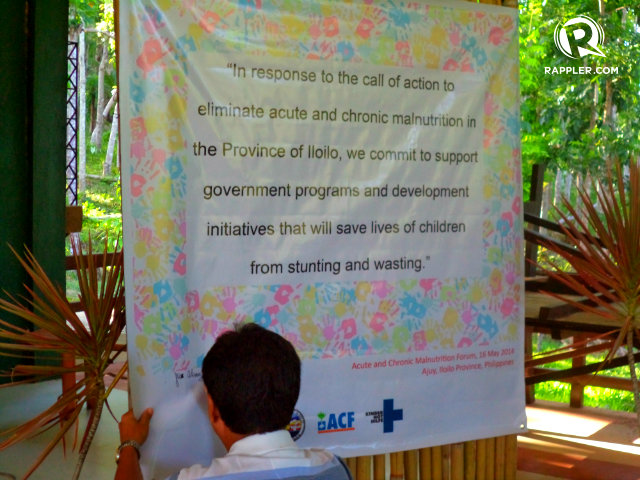

“Even before Yolanda, we already had lots of malnourished children in preschools,” Dr Patricia Grace Trabado, chief of the Iloilo Provincial Health Office, admitted during ACF’s Malnutrition Summit held on May 16 in Iloilo.

Trabado identified the increasing food prices, agricultural support, and the lack of infrastructure as some of the factors triggering the problem.

As of 2012, only 36% of households in Iloilo had access to safe water. In the entire country, 51% of households made no effort to make their drinking water safe, according to the 2011 National Nutrition Survey (NNS).

She also stressed how lack of information contributes to malnutrition.

“There are people unaware of proper nutrition. Like young mothers who don’t want to breastfeed, afraid of losing their figure,” she said.

In 2012, only 53% of mothers in Iloilo did breastfeeding exclusively. In the entire country, less than half of all mothers (47%) breastfed their infants exclusively during the first 5 months, according to the 2011 NNS.

The province of Iloilo called for action: a response to the country’s malnutrition cases dubbed a “silent emergency,” and more importantly, the prevention of malnutrition itself.

Iloilo aiming for change

To address its malnutrition issues, the province of Iloilo has been intensifying its efforts on IYCF or the Infant and Young Children Feeding program – which educates parents about the importance of proper care practices, maternal and infant health. It shares the following important information:

- Start breastfeeding within an hour after birth

- Exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months

- Introduce proper complementary food not earlier than 6 months

- Breastfeeding up to at least 2 years

- Proper diet and physical activities

- Involvement of both parents in securing a child’s nutrition

“All babies must be wanted, so they can be cared for, so they can develop fully,” she added.

The Iloilo province boasts of having the “most advanced” youth programs. Its teen centers provide counseling on adolescent health.

The province also implements immunization programs and food fortification or the addition of micronutrients to food.

Unfortunately, other parts of the country lack such initiatives.

“We hope that our programs can inspire other provinces, and at the same time, other LGUs can share their best practices in fighting hunger. We can all learn from each other,” Trabado said.

Action, not just words

Not all provinces, however, are like Iloilo.

What hinders the country from improving its malnutrition situation is the government’s failure to implement strong policies directly addressing malnutrition, its causes and effects, according to health advocates. (READ: PH vs Hunger)

“We need to make our leaders realize the importance of health and nutrition. They should prioritize and fund effective, sustainable programs,” Parreño stressed.

NNC, established in 1974, is the country’s highest policy-making body on nutrition. It is mandated by law to promote good nutrition and to coordinate with the government, the private sector, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in addressing hunger and malnutrition.

“Government and others in the development sector, as duty bearers, have the responsibility to assist those who are unable as of yet to enjoy the right to good nutrition,” NNC said in a statement.

The country’s main “response to malnutrition” is the Philippine Plan of Action for Nutrition (PPAN), a framework for improving the nutritional status of Filipinos. It recognizes good nutrition as a basic human right.

PPAN identified 5 main challenges:

- Hunger

- Child undernutrition

- Maternal undernutrition

- Deficiencies in iron, iodine, Vitamin A

- Obesity/Overweight

“NNC oversees the implementation of PPAN, but the implementation itself is done by different government agencies,” Kate Dimetreo, NNC nutrition officer, said in a phone interview.

The Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) and the Department of Education are implementing school feeding programs, while the Department of Health conducts “Operation Timbang Plus” (OTP) which identifies undernourished preschoolers and nutritionally-at-risk municipalities – these records are given to local government units (LGUs), concerned government agencies, and NGOs conducting interventions.

Parreño criticized the PPAN, asking if the framework is actually adopted. Advocates like him are looking for action-oriented programs delivering concrete results, instead of just guidelines.

“It looks good on paper,” advocates said. “But is it enough?”

Communities against malnutrition

One suggested intervention is the community-based management of malnutrition (CMAM); this is also promoted by PPAN.

Many NGOs, like ACF, already follow the CMAM model which provides medical and nutritional support for malnourished children within communities.

Such NGOs provide CMAM-training to health workers across different provinces like Iloilo; so that even after the NGOs leave the barangays, its local health workers can sustain the program.

In CMAM, each child is assessed, and treatment is based on individual needs and nutritional status.

Malnourished children suffering from diseases or infections are referred to health facilities where they are treated and get to receive therapeutic milk until they get better. Those without medical complications may be treated at home and are given Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF), which appears and tastes like peanut butter.

ACF acknowledged that RUTF alone is not a “silver bullet.” To be effective, an anti-malnutrition program has to be supported by government and backed up by infrastructure and systems.

Poor families in rural communities are malnourished largely because they lack access to safe water, markets that sell healthy food, and health care facilities. Also, there literally are no roads ahead.

Before the summit ended, a mother from Iloilo asked how come the Philippines is having a hard time solving malnutrition.

“Acute malnutrition is sporadic. But in total, over a million children are affected,” Parreño replied. Local surveys might show that each barangay only has a few cases of malnutrition, but adding all those up, the overall tally proves to be alarming.

“Because we are an archipelago, our efforts are spread out. LGU officials don’t put resources to nutrition,” Parreño said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.