SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Almost everyone is familiar with the political practice of assigning party-mates, friends, allies, and relatives to political positions as reward for support during the election season. This is such a common practice that it’s more surprising when a politician doesn’t appoint his or her family or cronies in prominent positions when they assume public office.

Almost everyone is familiar with the political practice of assigning party-mates, friends, allies, and relatives to political positions as reward for support during the election season. This is such a common practice that it’s more surprising when a politician doesn’t appoint his or her family or cronies in prominent positions when they assume public office.

What many don’t realize is that this practice has consequences that can lead to less-than-desirable nutrition outcomes and the loss of a career for many frontline nutrition workers.

The Barangay Nutrition Scholars (BNS) and other health workers refer to it as “Security of Tenure” or rather, the lack of it.

It’s an issue that’s been brought up by nutrition officers, health and social workers, volunteers, local chief executives, politicians, citizens, and the BNS themselves during training seminars all the way to national ceremonies.

A frontline nutrition worker’s job can sometimes be directly related to the whims of partisan politics. (READ: Life of a barangay health worker)

Who they are

That is not to say that we shouldn’t replace nutrition workers under certain conditions. Nutrition and health workers who underperform or use their positions in less than honest ways should definitely be candidates for replacement or retraining.

The issue is not them, but the almost seasonal replacement of health workers.

The effect on the efficiency of our local nutrition programs by this kind of partisanship is very obvious.

BNS are some of the primary implementers and advocators of the national and local programs and policies pertaining to nutrition. Their capabilities are important in the successful fight against malnutrition.

That’s why when experienced or trained nutrition workers are replaced with inexperienced personnel simply on the basis of whom they backed during the elections, this can negatively affect the nutrition situation in an area.

This kind of politicking affects our short- and long-term nutrition programs and policies. It affects our capacity to monitor the nutrition situations in barangays through Operation Timbang Plus, the application of supplementary feeding programs, and the dissemination of nutrition information, among other detrimental effects such as losing established intrapersonal connections.

Newer BNS also face the uphill battle of gaining respect within the community and local nutrition councils. Funds have to be released to train and capacitate these new BNS.

All of these hinder our ability to target and eliminate malnutrition in the country.

You can imagine the effects of these problems on children in need of nutritional support.

We lose our long-term monitoring of those who are nutritionally at-risk or who are already undernourished. Nutritional interventions aren’t a one-time thing. For a child to fully recover from malnutrition, a 120-day regimen of regular feeding must be undergone. This is in addition to taking into account the child’s medical history and pre-existing condition.

This kind of long-term tracking is usually lost once a BNS or health worker is replaced.

Politics, nutrition

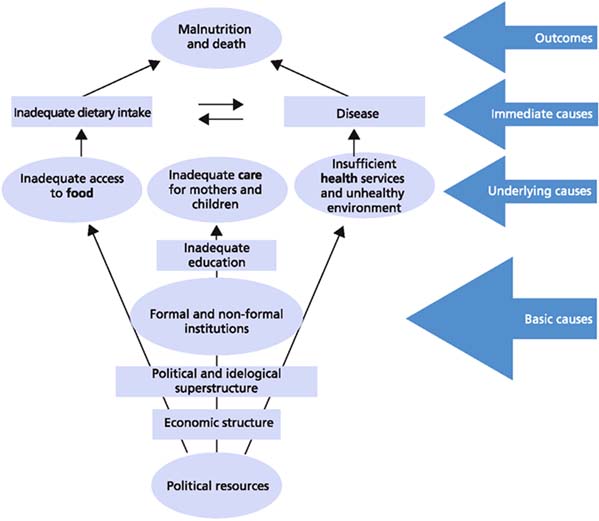

Many will doubt that partisan politics can have this big an effect on the situation in local areas. In 1990, however, Unicef published the “Causal Model of Malnutrition,” a tool that nutritionists and other health workers until now use to determine the cause of malnutrition in an area.

We can see that one of the basic causes is political superstructure. (READ: Health workers on the mountain top)

This has been shown to be true time and time again since the causal model was first published. Strong political will in changing the health situation in an area can lead to truly positive change but a weak and selfish leader will cause the opposite.

There is a real connection between politics and malnutrition.

It is sad to see that many local political leaders prioritize those who vote for them instead of those in need and this seems to reflect the overall political structure in the Philippines.

As much as we need political change at the local level to help eradicate malnutrition, we also need to eradicate this kind of politicking in the overall superstructure to bring about far-reaching change. – Rappler.com

Edwin Daryl Dy is a registered nutritionist-dietitian with a passion for research. Since graduating from the University of the Philippines-Diliman, Daryl has been involved in nutrition research and public health. He recently co-authored a study on nutrition and fast food consumption and is co-authoring researches on functional foods and nutrition information through mobile software. He is currently a nutrition officer in the National Nutrition Council-MIMAROPA.

What are the work conditions of BNS, nutrition and health workers in your community? Share your observations and suggestions, or report what your LGU is doing. Be part of the #HungerProject. E-mail us at move.ph@rappler.com.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.