SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – “Heaven and earth” was how Mohagher Iqbal, the chief negotiator of rebel group Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), described the gap between the government and their proposal during the early stages of negotiations under the Aquino administration in 2011.

A year later, the government and the MILF would sign a peace framework. By March 2014, the comprehensive peace accord based on that framework was signed.

The House of Representatives and the Senate were on track to pass the proposed law implementing the peace pact – until January this year, when the atmosphere changed after the clash in Mamasapano, Maguindanao, killed 67 persons, mostly elite cops.

Following the political fallout, a Senate committee report accused the government of giving too much to the MILF by allowing the creation of what some lawmakers consider a substate, which entailed a “high cost of appropriations.”

It took 17 years before the MILF could ink a peace pact with the government. How did the Aquino government secure the elusive accord?

Botched agreement

Before talks started under the Aquino administration, peace negotiations were smarting from the outbreak of violence that followed the Supreme Court decision declaring the Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain (MOA-AD) as unconstitutional.

The draft initial peace deal between the MILF and the Arroyo administration, in 2008, laid the foundations for what Associate Justice Conchita Carpio Morales said was “a state in all but name” within the Philippines. It sought to give the Muslim-dominated region “associative relations” with the national government – a set up that was not allowed under the Constitution.

The High Court halted the signing of the MOA-AD after local and national politicians decried the lack of public consultations.

The deal was declared as unconstitutional for guaranteeing constitutional amendments to create a substate without concurrence from Congress.

Arroyo abandoned the peace negotiations after disgruntled MILF combatants launched attacks in North Cotabato, Lanao del Norte, and Sarangani following the SC decision, killing close to 400 and displacing over half a million residents.

Before talks were scrapped all together, the MILF had filed a “Comprehensive Compact” that contained its proposal for a final peace deal based on the botched MOA-AD.

Starting positions

When talks resumed under the Aquino administration, the MILF submitted a revised version of the so-called Comprehensive Compact.

The MILF did not release the revised document, but it contained a similar proposal for a substate setup, designed to replace the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) and which could only be implemented through charter change.

Based on the summary released by the MILF, the proposal contains a formula reminiscent of the group’s desire for self-governance as stated in the MOA-AD. It was not a document seeking independence, then chief negotiator and now Associate Justice Marvic Leonen said in an interview with Mindanews.

Talks did not gain ground until the surprise meeting between President Benigno Aquino III and the MILF chair Murad Ebrahim in Tokyo, Japan, on August 2011.

During the meeting, Aquino and Murad agreed to fast-track talks to allow the government to implement the peace deal in less than 6 years or within Aquino’s term.

Learning from the MOA-AD, Aquino was adamant that the peace deal had to be within the bounds of the Constitution and would be implemented without the need for amendments. Charter change, after all, was not a priority of the administration (He would later toy with the idea of charter change, but for another reason.)

Weeks after the Japan meeting, the government submitted its counter-proposal to the MILF. Expectations were high. Dubbed as the “3 for 1” solution, the government offered to reform the ARMM, infuse economic development to the region, and retell history to correct the side of the Moros in the centuries-long struggle.

But the MILF was underwhelmed and rejected the proposal for being too “anemic.” Previous administrations had offered the ARMM to the MILF, but they refused to accept it. Some peace observers also remarked that the government offer did not need a peace agreement to be implemented.

Leonen, not giving up, meanwhile said he rejected the rejection, Mindanews reported.

Here is how the position of both parties moved on key aspects of the proposed expanded autonomous region:

1. Transition

The MILF wanted a total of 7 years of transition at the beginning of talks, with one year for the preparatory steps and 6 years for the transitional government itself.

After meeting with Aquino in Japan, Murad agreed to lessen it to 3 years, with the first half of the Aquino administration to be devoted to the negotiations and another half for the implementation.

But delays in the inking of the peace accord, the submission of the proposed law, and the unfortunate Mamasapano clash pushed back the timeline.

It did not help that the review of the proposed law in Malacañang before it was submitted to Congress lasted for two months. The MILF accused the government of diluting the original draft, while the government implied that the draft contained unconstitutional provisions.

With the bill still pending at the House and the Senate as of May 2015, there is only one year left to pass the bill in Congress, subject it to a plebiscite, and put the MILF-led transition body in place.

2. Form of government and power sharing

The parliamentary form of government was one of the aspects of the peace deal that the MILF fought the hardest for during negotiations with the Aquino administration, Sidney Jones director of the Jakarta-based think tank Institute of Police Analysis of Conflict (IPAC) wrote in a report.

In exchange for the creation of a parliamentary form of autonomous government with greater powers, the MILF committed to decommission its firearms.

The unconstitutional MOA-AD was founded on the concept of an associative relationship between the proposed Bangsamoro Juridical Entity (BJE) and the national government.

Under the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (CAB) and the proposed Bangsamoro basic law (BBL), the relationship between the central government and the Bangsamoro is “asymmetric.”

While the associative relationship is “characterized by shared authority and responsibility” with defined powers and functions, asymmetry is founded on the idea of devolution of powers from the national government to the Bangsamoro.

Leonen defined asymmetrical relationship in the case of the League of Provinces of the Philippines versus DENR to mean that “autonomous regions are granted more powers and less intervention from the national government.”

Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago is, however, unconvinced, concluding in a Senate report that the parliamentary form of government, which grants exclusive powers to the Bangsamoro, is unconstitutional.

The CAB and the proposed basic law delineates powers as exclusive to the Bangsamoro, reserved to the national government, and concurrent or shared between the two.

Former Chief Justice Hilario Davide meanwhile argues that, under the Constitution, the unitary and presidential system only applies to the national government. He said the Constitution permits a parliamentary form of government in local government units since the Constitution only requires that they should have an executive department and legislative assembly, which shall be elective.

3. Constitutional amendments

The main reason behind the junking of the MOA-AD as unconstitutional is the guarantee that the Constitution would be amended to implement the peace deal.

Under the CAB, the Bangsamoro Transition Commission (BTC) – the body that crafted the first BBL draft – could recommend revisions but there is no guarantee that they would be carried.

The BTC ended up not recommending specific revisions. When the BTC submitted the original draft to Malacañang, the MILF accused the government of watering down the draft, rendering the proposed Bangsamoro parliament weaker than the ARMM.

Malacañang, meanwhile, took two months to reconcile the original BBL draft with the Constitution. The difference in the positions forced both sides to negotiate the draft anew.

When the bill reached Congress, the House of Representatives took the position that the most important aspects of the measure were constitutional save for some provisions, while majority of senators are of the view that the parliamentary form of government proposed under the BBL is unconstitutional.

4. Territory and the opt-in provision

At the beginning of the talks, Iqbal said the MILF wanted to have a “modest share and taste of the remaining 7-9% of lands” where Muslims continue to be the majority, from the 98% that used to be dominated by Moros back when the sultanates ruled central Mindanao and Sulu.

An earlier peace accord known as the Tripoli Agreement of 1976 between former dictator Ferdinand Marcos Jr and the first group that led the armed conflict in Mindanao – the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) – identified 13 “areas for autonomy for Muslims in Southern Philippines.” These are:

- Basilan

- Lanao del Norte

- Sulu

- Lanao del Sur

- Tawi-Tawi

- Davao del Sur

- Zamboanga del Sur

- South Cotabato

- Zamboanga del Norte

- Palawan

- North Cotabato

- Maguindanao

- Sultan Kudarat

But Marcos implemented the peace deal without engaging the MNLF and subjected the identified areas to a plebiscite, which caused the group to reject it. Only 4 provinces voted for autonomy: Maguindanao, Sulu, Lanao del Sur, and Tawi-Tawi.

The MILF broke away from the MNLF at the height of the conflict in the 1970s due to leadership differences.

Another plebiscite was held in the 13 provinces after the administration of President Fidel Ramos signed another peace deal with the MNLF in 1996. However, only 5 provinces and one city voted to join, comprising the present ARMM. Marawi City and Basilan were the additions.

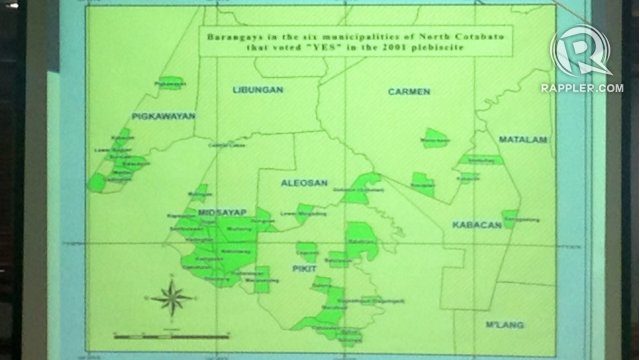

Under the MOA-AD, the present ARMM territory plus all other municipalities in Lanao del Norte and barangays in North Cotabato that voted yes to the ARMM in the 2nd plebiscite comprised the core territory of the Bangsamoro Juridical Entity (BJE).

The MOA-AD identified “special intervention areas” outside the BJE that would be the subject of special socio-economic and cultural programs. They would be allowed to join the plebiscite to join the BJE 25 years from the signing of the Comprehensive Compact.

The same core areas identified in the MOA-AD form the present core territory of the proposed Bangsamoro autonomous region.

But instead of a required plebiscite, areas sharing a common border with the Bangsamoro areas may file a petition to join the plebiscite for possible inclusion to the Bangsamoro. The petition should be signed by at least 10% of registered voters in the affected area. Under the peace deal and the BBL, contiguous areas may opt to join at anytime.

The so-called opt-in clause is said to be a killer provision for lawmakers. The House of Representatives’ committee introduced further limitations – only areas identified in the Tripoli Agreement and which share a common land border with the Bangsamoro may file a petition. The plebiscite may only be held 5 years and 10 years after the creation of the Bangsamoro and nothing more after that. Only provinces and cities would be allowed to join; municipalities and barangays were excluded.

5. Wealth-sharing and revenue generation

Some of the hardest parts of the negotiation were on the control over natural resources and how wealth in the Bangsamoro will be shared between the national government and the autonomous regional government. It was so difficult that it caused months of deadlock and a near breakdown in the talks.

The MILF negotiated for the Bangsamoro to have authority and control over the use and development of natural resources within the core areas, among others.

But the regalian doctrine under the Constitution states that all lands and natural resources in the public domain belong to the State.

The Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro gave the Bangsamoro “just and equitable share” in natural resources.

The government also agreed to change the characterization of minerals as “strategic” and “non-strategic,” which are political terms, to the more categorical “metallic” and “non-metallic.” The issue on strategic minerals is also one of the aspects that the MNLF said remains to be unimplemented in the 1996 peace deal.

Under the wealth-sharing deal in the final peace accord, the Bangsamoro is set to get 75% of government revenues from taxes and natural resources, up from 70% for the ARMM.

For fossil fuels such as petroleum, gas and coals, as well as uranium, the sharing scheme is 50-50.

The House of Representatives, however, reintroduced the term “strategic minerals” and excluded them from Bangsamoro authority and jurisdiction. In contrast, the original proposal sought to give the Bangsamoro and the national government shared jurisdiction over minerals.

Instead of just focusing on control over resources, the peace deal and the BBL designed measures to allow the Bangsamoro to raise revenues and not depend too much on the national government for funds.

The Bangsamoro parliament is designed to get a block grant or automatic appropriations, similar to the internal revenue allotment of local government units. The block grant would be 4% of the 60% IRA that goes to the national government – corresponding with the ratio of the population in the Bangsamoro to the rest of the country.

The parliament can impose tax holidays on taxes that were devolved to it and contract foreign loans. The House however introduced changes to these schemes.

6. Indigenous peoples, ancestral lands, and the Bangsamoro identity

When the Supreme Court declared the MOA-AD as unconstitutional, one of its strongest objections was rendered on provisions concerning the rights of indigenous peoples. The MOA-AD introduced a new scheme that would govern ancestral domains, without reference to the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA), which already has a scheme for native titles.

In his concurring opinion, Associate Justice Antonio Carpio said the MOA-AD would result to a “cultural genocide” with declaration that “it is the birthright of all indigenous peoples of Mindanao to identify themselves and be accepted as Bangsamoros.”

Carpio wrote:

It erases by a mere declaration the identities, culture, customs, traditions and beliefs of 18 separate and distinct indigenous groups in Mindanao. The “freedom of choice” given to the Lumads is an empty formality because officially from birth they are already identified as Bangsamoros. The Lumads may freely practice their indigenous customs, traditions and beliefs, but they are still identified and known as Bangsamoros under the authority of the BJE.

The issue over indigenous peoples’ rights continue to hound the present Bangsamoro basic law.

While the BBL no longer insists that it is the birthright of IPs to identify themselves as Bangsamoros, the proposed law does not include a definition of who the indigenous people are, unlike Republic Act 9054 or the ARMM organic law. The proposed BBL only defines who the Bangsamoro people are.

The MILF considers the inclusion of the IPRA in the House version of the BBL as a killer provision. The rebel group decried the transfer of the protection of the IP rights from exclusive powers to concurrent powers.

For the MILF, the indigenous peoples in Mindanao and the original Muslim inhabitants all come from the same ancestor, and may identify as Bangsamoro. Iqbal said the BBL provides for equal sharing in profits from resources, which is not guaranteed under the IPRA.

Some Moro groups, however, insist that IPs should be given due recognition in the BBL. The freedom of choice of Lumads under the BBL is respected.

7. Policing and decommissioning

Another issue that the MILF fought hard to get is giving the Bangsamoro parliament control over the police force in the region, Jones said.

Under the botched MOA-AD, Carpio assailed the lack of a clear disarmament scheme for MILF arms.

Carpio said the “obvious intention” of the MOA-AD was to constitute the present MILF armed fighters into the BJE’s internal security force.

With the MNLF back in 1996, qualified MNLF fighters were integrated into the military and the police. A scheme that encouraged but did not require MNLF fighters to surrender their firearms in return for cash proved to be unsuccessful; the money was only used to buy brand-new arms.

Under the current peace deal, the government and the MILF designed a comprehensive scheme for the return of MILF rebels to the mainstream. It includes livelihood programs for returnees.

There is a commitment from the MILF to decommission firearms. The process is staggered and is tied up with milestones in the implementation of the peace agreement, including its passage in Congress and through a plebiscite.

There is no designated program for the integration of MILF rebels into the police and the military, but qualified MILF rebels may apply for the position.

These are only some of the key issues that show how the peace process moved over the two decades of negotiations between the MILF and the government. With a number of issues left unresolved, and with such a tight deadline, will lawmakers manage to legislate a peace deal within the bounds of the Constitution? – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.