SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

TACLOBAN CITY, Philippines – The Eastern Visayas is no stranger to large-scale disasters.

Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) in November 2013 brought many towns of the region and other nearby provinces to their knees, wiping out coastal villages. It cut off water and power supply, and destroyed roads, bridges, houses and buildings. The government’s official tally pegs the dead at 6,190 with over 1,700 still missing.

In its aftermath, Yolanda destroyed 1.1 million houses and affected 16 million people.

But typhoons and storm surge aren’t the only hazards the island region faces. According to Philvolcs Director Renato Solidum during the PH+SocialGood: #2030NOW summit on in Tacloban City on Saturday, September 20, the seismicity of the region is also high, particularly in the provinces of Leyte and Southern Leyte. (Check out what happened at the PH+SocialGood: Tacloban 2030NOW)

Back in October 1897, Samar was witness to a typhoon, a storm surge, and an earthquake. In Laoang, buildings spared from the typhoon and storm surge were rendered helpless by the quake.

The first 45-second quake, according to accounts, leveled public buildings, churches, rectories, and schools. A second quake cracked the entire church of Oras, said Solidum.

So when planning, local, national and regional agencies shouldn’t only list down the hazards of one disaster. It should be ready for two, or all risks happening at the same time.

Disaster imagination

The Philippines is one of the countries most prone to natural hazards. At least 20 typhoons and storms visit the country each year, while various active faults make it vulnerable to earthquakes. The Philippines also has volcanoes, one of which – Mayon – has been restive in the last few weeks.

“Disaster Imagination,” said Solidum, involves identifying hazards, assessing them, understanding the risks, and pinpointing the possible impact and damage that will be caused by the hazard.

Weaved through the phases of disaster imagination are pre-disaster, mitigation, and recovery plans.

Worst scenarios

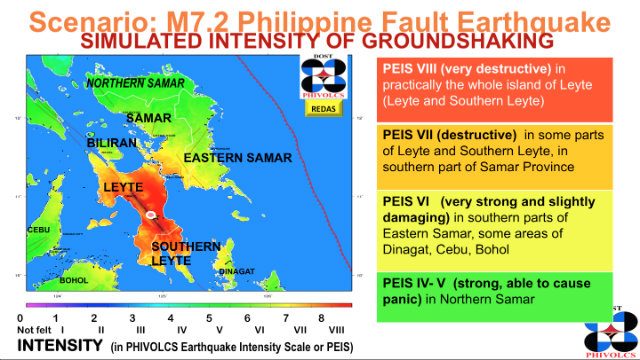

What would happen to the Eastern Visayas in the event of a Philippine fault earthquake? Solidum said the island of Leyte, where the province of Leyte and Southern Leyte are located, would be worst hit.

According to the Phivolcs Earthquake Intensity Scale, Leyte and Southern Leyte would be devastated in the event of a magnitude 8.2 Philippine Fault earthquake.

At intensity 8, people would “find it difficult to stand even indoors.” Well-built buildings would not stand a chance, with “concrete dikes and foundation of bridges destroyed by ground settling or toppling.”

Intensity 8 to 9 was felt at the epicenter of the 2013 Bohol earthquake.

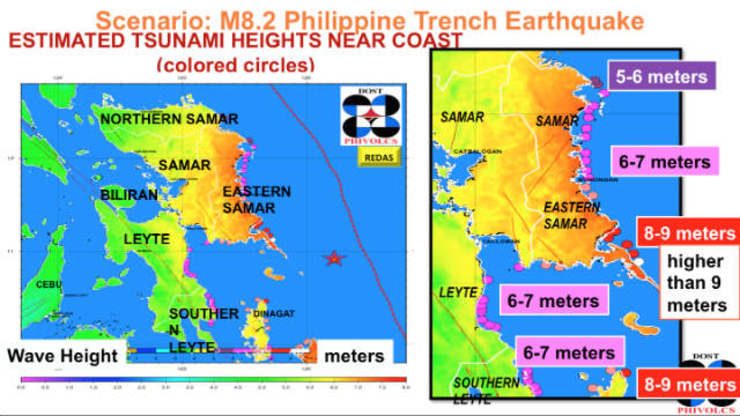

Should a magnitude 8.2 Philippine Trench quake happen, coastal towns in Eastern Samar would be in danger of a tsunami of up to 9 meters, Solidum said.

Even coastal towns in Leyte may also see 6-7 meter high waves – aside from Tacloban, Palo and Tanauan towns, which were also witness to the strong storm surge during Yolanda. The nearby province of Dinagat is also at high risk, and may see 8-9 meter-high tsunamis.

Single mindset

But Solidum emphasized that planning works only if all levels of government – from national to the local government units – are on the same page.

“Disaster imagination of different leaders cannot be different,” he said.

Conflicting stands of local and national government can be confusing and sometimes, crippling. Yolanda was proof of this. (READ: Haiyan crisis: No ground commander)

Recalling the aftermath of the storm, Tacloban City Mayor Alfred Romualdez said only 10% of the city government’s workforce showed up on November 8, 2013. Only a handful of the city’s 300-strong police force reported for duty.

Help from national government came in trickles – not only in Tacloban, but in other towns as well. Some survivors were left without outside help for almost a week.

Based on government protocol, it’s the local government units (LGUs) that are the first-responders in any calamity. Only after 2-3 days would the national agencies come in to assist.

But Yolanda’s magnitude was unprecedented. (READ: 6 months after Yolanda: ‘We are failing’)

“We need a national agency that would focus solely on natural disasters like FEMA [in the USA]. That’s important because protocols change during a disaster and the level of response also varies. When you have different levels of response, the protocol for communication also changes,” said Romualdez during the Q&A portion of the summit.

Watch Solidum’s speech below.

Tacloban became notorious in the weeks following Yolanda for what was perceived to be politics and personal history getting in the way of disaster response. The mayor is a relative of former First Lady Imelda Marcos. Marcos’ husband, former dictator Ferdinand Marcos, put President Benigno Aquino III’s father, then-Senator Benigno Aquino Jr, to jail.

The Romualdezes are allied with the opposition.

The mayor initially wanted to declare “martial rule” over the city. Days after Yolanda, chaos was evident. Looters began raiding business establishments and reports of people breaking into homes spread. But the national government did not budge, urging the local government to first pass a resolution on it.

A meeting between Romualdez and Interior Secretary Manuel Roxas II, parts of which were leaked and spread online, gave a glimpse of the divide between the two. “You’re a Romualdez and the president is an Aquino,” uttered by Roxas and captured in the video, summarized the situation in the eyes of many.

From science to action

That is not to say the government failed to warn the country of Yolanda’s perils. Aquino himself, in a televised statement, warned Eastern Visayas of the wrath of the storm. Strong wind and storm surges would need strong preventive measures from local government.

Unfortunately, Romualdez said, it wasn’t quite enough. “When you listen to forecasters and they said, you’ll have a category 5 typhoon and you’ll have a 6 to 7 meter storm surge… do [people] really understand how far the storm surge will go?” he said.

“We’re learning that we have to translate scientific information to our people so that it can be better appreciated and understood. So that we can be better prepared,” Romualdez added.

It’s a weakness that the National Disaster Risk Reduction Council (NDRRMC) acknowledges. Before the 2014 “storm season” in the Philippines began, Roxas, vice chairman of the NDRRMC, said it would be council’s goal to take scientific jargon into “actionable steps.”

NDRRMC chair Undersecretary Alexander Pama said this would mean every LGU would create a template for every type of risk that would vary depending on the situation and resources of an area.

But it shouldn’t stop there, said Solidum. “Possible hazards and its effects in localities and the whole region must be imagined,” he added.

The NDRRMC introduced a “twinning” of regions in times of disaster. Should one region be unable to pick itself up after a calamity, its “twin” region should be ready to step up any time. (READ: Who will help earthquake-hit Metro Manila?)

But Leyte locals at the event pushed for a partnerships within the local government units of a province and even between provinces in times of disaster. Romualdez and Leyte Governor Dominic Petilla admitted it’s already been discussed but has not been finalized. (READ: 2014 PH+SocialGood Summit Unity Statement)

Almost a year after Yolanda, the “imagination” of leaders has arguably improved. Which is not surprising. Yolanda, after all, was a disaster nobody imagined would hit them in the first place. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.