SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Decades after the Philippines began its labor migration policy in the 1970s, overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) are now widely touted as “bagong bayani” or modern-day heroes. (READ: ‘INFOGRAPHIC: Getting to know the OFWs‘ )

According to the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA), there were a total of 1,832,668 OFWs in 2014 – 1,430,842 land-based and 401,826 sea-based. Just about anywhere in the world, you’re bound to meet a Filipino. (READ: ‘What you need to know about overseas Filipino workers‘ )

Remittances from OFWs has helped keep the Philippine economy afloat. Data from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas show that in 2014, personal remittances from OFWs hit almost $24 billion (P1.178 trillion). Meanwhile, OFW cash remittances from January to August in 2015 reached $16.21 billion (P764 billion)*.

Despite their contributions, OFWs continue to face problems on basic services, harassment, security, among others. While every president for the past 4 decades recognized the significant role OFWs play, each one had a different approach in dealing with issues concerning them.

Unlike his predecessors, the administration of President Benigno Aquino III has been focused on “bringing the OFWs home” or making overseas employment an option and not a necessity. He consistently emphasized this in his State of the Nation Addresses throughout his presidency and whevever he addressed Filipino communities overseas.

Despite this, the outgoing president, has had a love-hate relationship with Filipinos abroad throughout his term.

From corruption allegations to diplomatic hits and misses, let’s take a look at some of the key OFW issues during the Aquino administration.

2010

Quirino Grandstand hostage crisis

While not directly related to OFWs, the hostage-taking of a tourist bus at the Quirino Grandstand on August 23, 2010, wherein 8 Hong Kong nationals were killed, became a major cause of concern for Filipino workers in Hong Kong. It took almost 4 years for the Philippines and Hong Kong to resolve their differences on the issue.

Immediately after the hostage incident, Hong Kong officials criticized the way Philippine authorities handled the crisis and issued travel advisory to its citizens on the Philippines. The Hong Kong government demanded a thorough investigation, compensation for the victims, and an apology from the Philippine government.

While the administration complied with their first two demands, President Aquino refused to issue a formal apology. Instead, he delivered a statement in a midnight press conference just hours after the tragedy to express his “deepest condolences” to the families of the casualties and the Philippines’ “deep feelings of sorrow” over the tragedy.

Meanwhile, tensions were escalating in Hong Kong. There were reports of aggression towards Filipino workers, and employers threatening to fire Filipino domestic helpers.

Migrante International criticized Aquino’s “no-show” throughout the negotiations with the hostage-taker, though the Chief Executive met with Manila officials and authorities in charge of the negotiations. It said that his “lack of political savvy and insensitivity caused a diplomatic row with the Hong Kong government.” (Years later, Aquino would admit that he regretted not talking to the hostage-taker.)

In February 2014, Hong Kong issued sanctions on visa-free entry for Philippine government officials and diplomats in the absence of a government apology. Hong Kong Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying said that this response was “unacceptable.”

Aquino refused to apologize in behalf of the government, saying that the hostage-taking incident was the “act of one individual” who was “probably mentally unstable.”

In an interview with the New York Times on February 5, 2014, Aquino said apologizing to Hong Kong would cause legal problems. He noted that even China had not apologized to the Philippine government nor paid compensation to the families of Filipinos killed in that country.

He was referring to, among others, a doctor touring with her family at the Chinese capital’s biggest square, who was among the 5 people killed in Tiananmen Square on October 28, 2013, when a vehicle plowed through the crowd.

The Philippines and Hong Kong finally resolved their dispute in April 2014. This was after then Cabinet Secretary Rene Almendras, Manila Mayor Joseph Estrada, and Philippine National Police (PNP) Chief Alan Purisima visited Hong Kong to bring compensation to the families of the victims.

The Philippine government, however, still refused to apologize, and instead expressed “its most sorrowful regret and profound sympathy” and extended its “most sincere condolences for the pain and suffering of the victims and their families.”

A joint statement released by the two governments on April 23, said that “the HKSAR Government and the Government of the Republic of the Philippines have agreed that the 4 demands made by the victims and their families on apology, compensation, sanctions against responsible officials and individuals, and tourist safety measures” had been resolved.

All sanctions have since been lifted by Hong Kong.

Read more here:

- Lim liable for Luneta bloodbath – Robredo report

- Palace: No basis for Lim’s Luneta neglect

- Manila hostage crisis: Hong Kong presses for apology

- 2010 hostage crisis victims: PH gov’t not doing enough

- China to PH: Don’t forget HK hostages

- DFA on Erap’s HK apology: Aquino’s stand prevails

- HK hostage kin sue Philippine gov’t

- HK to Manila execs: Sorry not enough

- Should the Philippines apologize to Hong Kong?

- HK apology? No way, says Aquino

- HK to PH: Apologize for officials who mishandled crisis

- Luneta crisis: Erap to meet Hong Kong officials April 24

- What happened to cops in Luneta hostage-taking crisis?

- Hong Kong, Philippines resolve hostage crisis issue

- Almendras: Palace did spade work in ending HK row

- Aquino still has regrets over HK bus hostage crisis

2011

Execution of Filipino drug mules in China

Three Filipino drug mules were executed in China. Concerns grew as the number of convicted drug mules in China continued to rise in 2011. In March that year, the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) said that 72 Filipinos were on death row for drug trafficking.

Convicted Filipino drug smugglers Sally Ordinario-Villanueva, Ramon Credo, and Elizabeth Batain were executed in China on March 30, 2011, via lethal injection, despite the Philippine government’s last-minute appeals for clemency.

The 3 were nabbed in separate arrests in 2008 for smuggling heroin – a crime punishable by death in China.

“Until the last moment, we did everything we could to save the 3,” said Vice President Jejomar Binay, then the Presidential Adviser on OFW concerns, said in a television interview.

Before the execution, Aquino, as relayed by then Justice Secretary Leila de Lima, ordered a probe into how the 3 convicted OFWs were able to leave the country carrying illegal drugs.

Migrante International blamed the lack of legal assistance from the government for OFWs in death row. “Iisa ang sinasabi ng lahat ng mga OFWs at pamilya, kulang na kulang ang pag-asikaso ng gobyerno,” said Migrante International in a statement.

Read more here:

- Appeal for Filipino on China death row

- Binay heads to China for Filipino on death row

- OFW on China death row meets family one last time

- Filipina drug mule in China executed

- NBI hunts down syndicate of Filipina drug mule

- Stop saving drug mules abroad, gov’t told

- Want no more drug mules? Reform our agencies – Sotto

2012

Closure of Philippine embassies

In 2012, OFWs and migrants’ rights groups slammed the Aquino administration following the DFA announcement that it was closing several embassies and consulates.

Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario first revealed the plan to scrap 12 foreign posts in October 2011. This was trimmed down to 10 posts (7 embassies and 3 consulates) the following year.

The DFA cited “budgetary constraints” for the closures but assured that this would have a minimal effect on consular services for Filipinos in affected areas. It said the move was meant to put more resources in areas with a bigger concentration of Filipinos, such as the Middle East.

The closures pushed through despite protests by OFWs in affected areas and migrants’ rights groups. According to a 2012 Inquirer report, Palau President Johnson Toribiong even appealed to Aquino to not close the Philippine embassy in Palau, citing the presence of some 5,000 Filipinos there.

2013

Sex-for-flight scandal

In one of the biggest OFW-related scandals to rock the Aquino administration, Akbayan Representative Walden Bello and 3 victims from Syria, Kuwait, Jordan – and later – Saudi Arabia, accused Philippine embassy staff in the Middle East of sexually abusing and prostituting distressed OFWs.

In the so-called sex-for-flight scheme, suspects allegedly promised to prioritize victims for repatriation in exchange for sexual favors. Bello’s exposé ignited separate investigations by the DFA, the labor department, and the Senate.

Since June that year, numerous cases related to the sex-for-flight scheme have been reported. The DFA ordered 11 envoys were ordered to return home, pending investigation.

In the first week of July, t he labor department submitted a report to Aquino detailing the measures it took since the scheme was made public, and recommendations for the government to avoid similar incidents.

A week after the submission, DOJ Secretary De Lima also said the National Bureau of Investigation was probing similar cases even prior to Bello’s exposé.

Aquino ordered the labor and justice departments to work together in filing cases against the erring officials.

On August 15, 2013, the accusers, wearing masks, faced the accused, Riyadh assistant labor attaché Antonio Villafuerte, at a Senate probe.

One of them, known only by the name “Michelle,” decided to remove her veil and challenged her alleged abuser. “ Ngayon, Mr Villafuerte, naaalala mo po ba ako, ‘yung ginawa mo sa akin? Naaalala ‘nyo po ba? Huwag kayong magsisinungaling dahil hindi lamang po ako ang nakakita no’n.”

(Now, Mr Villafuerte, do you remember me, what you did to me? Do you remember? Don’t lie because there were other witnesses.)

On September 25, 2013, the first charge was filed against an unnamed labor attaché. The accused allegedly forced the victim, an OFW, to kiss him and attempted to take off her clothes.

In April 2014, Villafuerte was absolved of 3 counts of administrative charges of sexual harassment for lack of factual basis. He was, however, reprimanded for uttering lewd jokes to one of the 3 complainants.

Meanwhile, two labor officials – former Riyadh labor attaché Adam Musa and then acting labor attaché for Jordan Mario Antonio – were suspended due to administrative cases filed against them.

Musa was suspended for one month for his alleged attempt to cover up a sex abuse case involving his driver in Saudi Arabia, the subject of an OFW’s complaint.

Meanwhile, Antonio was slapped a 4-month suspension without leave for using “vulgar and indecent language” while talking to distressed workers.

In May 2014, Bello accused the government of lack of action in trying to “hold erring officials accountable.” The report by the Overseas Workers Affairs committee headed by Bello said none of the accused has been convicted in court.

Read more here:

- ‘Embassy staff prostituting OFWs’

- Sex-for-flight scheme just ‘tip of the iceberg’

- Sex cases prompt changes in halfway houses

- Charges set vs embassy staff over ‘sex for flight’

- DOLE says accused labor official has clean record

- De Lima: 3 more cases in ‘sex-for-flight’ scheme

- Stricter rules in OFW halfway houses out

- Labor chief’s report on ‘sex for flight’ now with PNoy

- Senate to have own sex-for-flight probe

- Whitewash feared in sex-for-flight probe

- Sex-for-flight probers target halfway houses

- Envoy hit for ‘inaction’ over OFW abuse

- DOLE threatened with budget cut

Repatriation of OFWs in Saudi Arabia

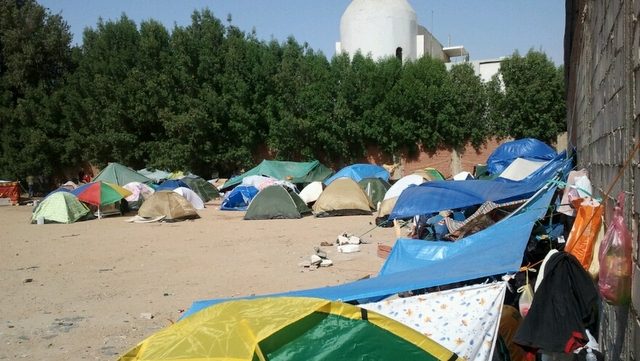

In 2013, Saudi Arabia began a crackdown on illegal foreign workers. Filipinos were given only until November 4 to find sponsors or leave. Hundreds of Filipinos without funds nor sponsors camped out in front of the Philippine embassy for weeks and braved the heat while waiting for assistance from officials.

The government has allotted P2 billion for OFWs returning home from the Kingdom.

In January 2014, the DFA announced that it has already repatriated 7,177 OFWs and planned to repatriate 1,000 more that year.

Up to 9,000 Filipinos initially requested repatriation, but Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario said the “indecision” of OFWs delayed them from coming home.

Balintang Shootout Incident

On May 9, 2013, there was shootout in the Balintang Channel near the Batanes group of islands between a poaching Taiwanese fishing vessel, and personnel of the Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) and the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR). It resulted in the death of a Taiwanese fisherman, straining ties between the Philippines and Taiwan.

According to the Philippine government’s incident report, the PCG-BFAR account alleged that the Taiwanese fishing boat was trespassing on Philippine territory. Even after the PCG announced its presence and signalled it to stop, the boat did not comply and instead performed evasive maneuvers. The coast guard personnel then chased after the boat and fired at it, killing fisherman Hong Shi-Cheng.

Taiwan strongly condemned the incident and rejected apologies by the Philippine government as inadequate. It retaliated with a series of sanctions, including a ban on hiring new Filipino workers, an advisory urging Taiwanese not to visit the Philippines, and the suspension of trade and academic exchanges. This left 16,000 overseas Filipino workers temporarily jobless for 3 months.

The Philippine government, for its part, quickly conducted an investigation into the shootout. By August 2013, the government released an incident report. The Taiwanese government also conducted a separate investigation.

Diplomatic tensions eased only after Philippine authorities said they had recommended homicide charges against 8 Filipino coast guards for Hung’s death.

On March 27, 2014, the Batanes Regional Trial Court filed homicide charges against 8 Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) personnel.

Obstruction of justice charges were also filed against two coast guard personnel before the Cagayan Municipal Trial Court for allegedly preparing and submitting a “falsified” monthly gunnery report related to the incident.

The 8 PCG personnel charged of homicide argued that their actions were done in self-defense and were “consistent with the regular performance of their legal duty.” They sought a dismissal of the case.

In April 2016, a Taiwanese court ordered the 6 PCG personnel to NT$3.198 million (P4.55 million) to the victim’s family. The Inquirer report, the Taiwanese court ruled that the Philippine personnel had a “criminal intent to kill” and while “the debt incurred from the infringement act is subject to the law of the place of the infringement act,” Taiwanese law applied insofar as civil claims were concerned.

Read more here:

- Homicide charges set over Taiwan fisherman’s death

- Coast Guard in Taiwanese fisherman shooting post bail

- Arrest of PCG leader in Balintang shooting sought

- Balintang incident: Coast guards ask DOJ to reverse indictment

- SC transfers Balintang shooting case to Manila court

- PCG allows Taiwanese team to question crew

- Standing firm against Taiwan’s strong-arm tactics

2014

Repatriation of OFWs in strife-torn Libya

The fighting between rival militias in Tripoli put 13,000 Filipinos at risk, and the government raced to get them home unscathed.

Libya has suffered chronic insecurity since dictator Moammar Gaddafi was overthrown in 2011. The new government has been unable to check militias that helped remove him and faced a growing threat from Islamist groups.

Fighting between rival militias in Tripoli and bloody clashes between Islamists and army special forces in the eastern city of Benghazi put 13,000 Filipinos in Libya at risk, prompting the Philippine government to try and bring them home in August 2014.

On August 4, 2014, however, DFA spokesman Charles Jose said up to 11,000 of the 13,000 Filipinos in Libya – or 84.6% – have chosen to remain in Libya because they fear joblessness back home.

While shunned by 8 out of 10 Filipinos in Libya, the efforts to bring them out of the conflict-stricken country could cost more than P169 million, Rappler’s computations based on government estimates showed.

2015

Mary Jane Veloso

2015 witnessed a glorious moment for Filipinos all over the world – the day Mary Jane Veloso, an OFW on death-row, was spared from execution.

Veloso, a Nueva Ecija native, was detained in Indonesia on April 25, 2010, for smuggling drugs, a crime punishable by death in a country known for having some of the toughest anti-drug laws in the world.

She claimed that her recruiter and godsister, Maria Kristina Sergio, had duped her into flying to Indonesia and with a suitcase bearing 2.6 kilograms of heroin hidden in the lining. Veloso has consistently maintained her innocence.

From 2011 to 2015, the Philippine government led by President Aquino appealed for clemency from then Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and his successor, Joko Widodo. Both of them continuously denied all requests.

By 2015, there was a growing public outcry to save Veloso. Migrante International kicked off an online movement, #SaveMaryJane, in March or more than month before her scheduled execution. Other groups started joining the campaign, including Rappler’s civic engagement arm, MovePH.

The online petition on Change.org was pushed to the top 10 of the most signed petitions globally.

On Tuesday, April 28, Aquino sent a fourth letter of appeal to President Widodo.

By Wednesday, the day of Mary Jane’s execution, all hope seemed lost.

But at the 11th hour, the whole country rejoiced when the Indonesian government gave Mary Jane a reprieve.

Read more here:

BalikBayan box

The Bureau of Customs received widespread comdemnation among OFWs when Commissioner Alberto Lina warned them against abusing balikbayan box privileges. OFWs accused the BOC of stealing from their boxes. Aquino eventually ordered the BOC to stop random and arbitrary inspection of balikbayan boxes.

On August 19, 2016, the Bureau of Customs (BOC) got on the nerves of OFWs when it issued a warning on abusing the balikbayan box privileges.

OFWs and advocacy groups condemned “the dictatorial and arbitrary manner by which the BOC has chosen to approach the balikbayan box issue.”

OFWs from around the world turned to social media to express their disappointment and complaints about items in their balikbayan boxes that were reportedly stolen or damaged upon “inspection.”

Deputy Presidential Spokesperson Abigail Valte assured OFWs that the BOC reminder is a deterrent to smuggling and not meant to single out OFWs. No government explanation, however, could appease the OFWs.

Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago filed a resolution urging the Senate to probe the BOC’s plans to inspect balikbayan boxes. This is in response to some 78,000 Filipinos who asked her via online petition platform Change.org to stop the plan.

On August 24, Aquino ordered the Bureau of Customs (BOC) to stop the random or arbitrary physical inspections on balikbayan boxes.

Read more here:

- Aquino signs law increasing tax-exempt value of balikbayan boxes

- OFWs: Hands off our balikbayan boxes!

- HK OFWs protest extra charges on balikbayan boxes

- Customs’ Bert Lina: Be honest, declare what’s in your #BalikbayanBox

- OFW groups seek dialogue with BOC on balikbayan boxes

- Aquino stops ‘physical’ check of balikbayan boxes

- How Aquino caved in to online rage vs balikbayan box rules

- Customs releases revised rules, regulations on balikbayan boxes

Laglag bala

The Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA) gained another blackeye when reports of a bullet-planting scheme in the international gateway spread, raising fears among OFWs and travelers.

In October 2016, reports of the laglag-bala (bullet-planting) scheme at the NAIA hit social media, infuriating the public and catching the attention of both local and foreign media outlets.

The modus: bullets were allegedly planted in the luggage of random NAIA passengers. The alleged perpetrators – NAIA employees – would threaten to arrest the passengers and ban them from leaving the country if they do not pay a fee.

The incident sparked public outrage, while travelers, in general, feared falling victim to the scheme.

Palace Communications Secretary Herminio Coloma Jr downplayed the issue and said only a few had been supposedly victimized compared to the thousands who pass through the airport. He added that there were enough officials and help desks in airports nationwide to respond to the problem.

Transportation Secretary Joseph Emilio Abaya said on November 2 that his office stepped measures to stop the alleged scam, assuring passengers that authorities were exhausting all means to stop it.

The next day, Presidential spokesperson Edwin Lacierda said the President gave “further instructions” to the transportation department “to refine the efforts underway.”

Authorities had also pointed to the practice of some travelers to bring with them amulets in the form of live bullets.

Read more here:

- How to curb ‘laglag-bala’ modus and airport extortion

- Gov’t won’t tolerate ‘laglag bala’ – Abaya

- First airport laglag-bala complaint filed with NBI

- ‘Laglag-bala’ probe: Palace looking into bullets as amulets

- NCR Aviation Security Unit chief sacked amid NAIA ‘laglag-bala’ scam

- Laglag-bala scheme embarrassing, alarming – De Lima

- Ex-cops, soldiers now congressmen: Replace NAIA chief over laglag-bala

- 4 airport police skip DOJ hearing on ‘laglag-bala’ case

- 40 airport security staff under investigation

2016

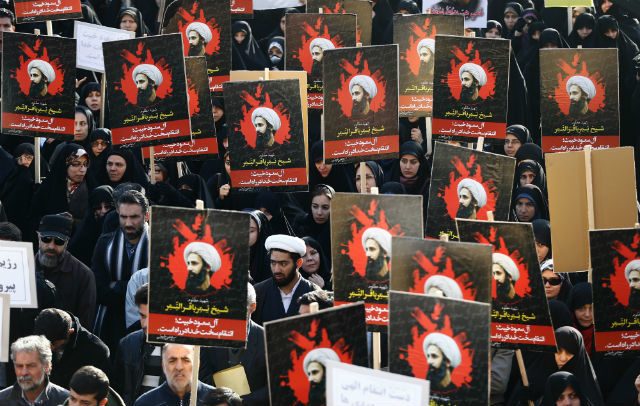

Saudi-Iran rift

When the execution of a Shiite cleric fueled a crisis between regional rivals Saudi Arabia and Iran, President Aquino quickly ordered his government to keep more than a million Filipino workers safe.

On January 8, President Aquino assured Filipinos in the Middle East that the government is ready to protect them, just as it had done to Filipinos in Libya during the Arab Spring.

He said Philippine embassies in the Middle East have been ordered to review their contingency plans, and update and double-check contact details of Filipinos in their respective areas, so they can be easily be tracked down when necessary.

The President also assured everyone that the country has the capacity to absorb displaced OFWs and “get them gainfully employed in case all of them are repatriated.”

Read more here:

Customs Modernization and Tariff Act

Considered as his parting gift to OFWs, Aquino signed the Customs Modernization and Tariff Act (CMTA) which is seen to reduce corruption in the Bureau of Customs, as well as technical smuggling in the country.

The CMTA increases the tax-exempt value of items sent via balikbayan boxes by OFWs to their families back home. Under CMTA, the tax exemption ceiling is increased from P10,000 to P150,000. (READ: ‘ Aquino signs law increasing tax-exempt value of balikbayan boxes‘ )

Are you an OFW? What are your thoughts on the performance of the Aquino administration? Tell us in the comments or write them on X! – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.