SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

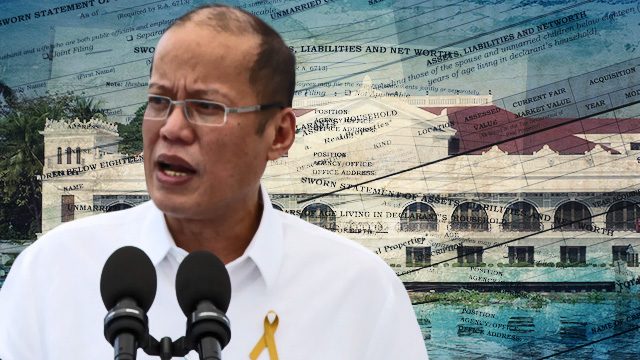

MANILA, Philippines – The non-passage of the Freedom of Information (FOI) bill under his term is considered as among Benigno Aquino III’s biggest failures as president since it was among his campaign promises.

When he launched his presidential bid in 2010, Aquino committed to pass the FOI bill. He said that his administration “will ensure transparency and citizen’s participation” by supporting “the enactment of the Freedom of Information Bill in Congress.”

The vow to foster greater transparency in government and weed out corrupt officials – through various reforms, including an FOI law – had prompted more than 15 million Filipinos to elect him president in 2010.

Promises of FOI legislation continued when he assumed power. Amid delays and doubts, Aquino convinced the nation year after year that the thoroughly-debated measure – a supposed hallmark of his anti-corruption drive – will be approved before he hands over the reins to his successor.

Six years went by. The Freedom of Information bill remains stuck in Congress.

What exactly happened?

Freedom of Information bill

In 2013, the House of Representatives debated whether to call the measure Freedom of Information or Access to Information. Regardless of its name, the pro-transparency measure serves a common purpose: to set up a system that prescribes procedures and defines limitations for citizens’ access to government record and data.

Why does the country need an FOI law?

“As scholars, we view access to data as an integral component in evidence-based research. Currently, the arbitrary roadblocks sent by public offices are barriers to a sincere examination of government operations,” a group of academics from the University of the Philippines said in a statement.

In an effort to answer this question, Rappler, with the support of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation, analyzed freedom of information laws in other parts of the world in 2014. We noted these common features in the laws we studied:

- An overall policy making information available

- Limits of access

- Prescribed process by which information may be accessed, cost of access, and processes for appealing request refusals

- In recent cases, measures to ensure that access policies are enforced through oversight bodies and penalty clauses

In other words, the FOI bill seeks to address a problem that has long plagued the ranks of Philippine bureaucracy: corruption. The goal of the measure is to help reduce corruption and abuse of office by making processes and records more transparent to the public who could help hold government offices accountable.

What happened in the 15th congress?

Compared to how Congress acted swiftly on the impeachment of the late Chief Justice Renato Corona and the passage of the sin tax bill, the FOI bill moved at a snail’s pace in the 15th Congress.

Advocates blamed Aquino’s observed passive approach and his supposed change of heart towards the bill. In October 2011, Aquino, for the first time, aired his apprehensions about the measure and said that while FOI is noble, “you’ll notice that here in this country, there’s a tendency of getting information and not really utilizing it for the proper purposes.”

The first FOI hearing at the House committee on public information, chaired by Eastern Samar Representative Ben Evardone, commenced as early as November 2010. But it wasn’t until January 2012 when the interagency body tasked to draft the Palace version of the FOI bill finally submitted its draft to the House.

Without the stamp of urgency from the president, several factors hampered the progress of the FOI bill at the House. Once, a meeting got postponed because there was no room available.

Before 2012 ended, the Senate managed to approve its version of the FOI bill, formally called the People’s Ownership of Government Information (POGI) Act of 2012.

Meanwhile, delays dragged on at the House until Congress went on a long break for the 2013 midterm elections. The FOI bill only managed to hurdle the committee level.

Open government without FOI?

While the Aquino administration failed to have the bill passed, it doesn’t mean it did nothing to introduce and encourage citizen participation and open governance. As soon as Aquino assumed the presidency, his administration made big strides and laid the groundwork for promoting transparency in the bureaucracy.

The Aquino administration implemented full disclosure policies, the “seal of good local governance,” a cashless purchase system, and inaugurated its open government data web portal, to name a few. The government’s bottom-up budgeting and citizen participatory audit projects even bagged international awards for two consecutive years from the Open Government Partnership.

However, critics say that without a measure that institutionalizes these reforms and gives flesh to the constitutional provisions guaranteeing public access to information, these gains are futile.

As what former Quezon Representative Lorenzo “Erin” Tañada III said in 2011, “he (Aquino) has to understand that, even as he keeps on saying his administration is transparent, this institutional reform is not for his term, because we don’t know if the next administration will be as transparent” as his. (READ: Gov’t making access to information harder)

Renewed hope in 16th Congress

Nevertheless, the start of the 16th Congress renewed hopes for the passage of the pro-transparency measure. For their part, advocates did not leave the passage of the bill solely in the hands of the legislators.

After the FOI bill languished in the legislative mill for more than two decades, the Right to Know, Right Now! Coalition filed an “indirect initiative” for their version of the FOI bill, dubbed as the “People’s FOI Act,” on the first day of the 16th Congress.

Advocates of the bill also launched an online signature campaign in May 2014 for its passage.

The pro-transparency bill gained more significance following the exposé on the pork barrel scam, the biggest corruption scandal in recent Philippine history. Advocates such as Ateneo School of Government Dean Tony La Viña said that a silver lining to the PDAF scam and DAP controversy is the urgency it brings to the passage of the FOI bill.

“Can you imagine, if we have the FOI, even before the money was spent, the [Department of Budget and Management] would be compeled to present and post the projects beforehand, not just after the fact,” Senator Grace Poe said in forum co-organized by Rappler on July 2014. Poe is the principal sponsor of the FOI bill in the Senate.

The Senate heeded calls for the urgent passage of the bill. In March 2014, barely a year since the 16th Congress started, the Senate passed the FOI bill on third and final reading with 22 affirmative votes, no abstention, and no negative vote.

As it did in the past, however, the House held up the rest of the pack.

Despite the delays in the lower chamber, the Palace remained confident, a view shared by watchdogs. It would be ridiculous for the FOI not to be passed under Aquino’s term, Vince Lazatin, executive director of the Transparency and Accountability Network, told the Senate public information and mass media committee at its first hearing on the measure in September 2013.

This promise was echoed by Aquino’s allies in Congress. In an effort to assure advocates, Speaker Feliciano Belmonte Jr even joked in 2013 that he could be “hanged” if the bill wouldn’t be passed in the 16th Congress. (READ: FOI by 2016? We will surprise senators, House says)

“Ipinangako ko during the 16th Congress. Kahit bitayin ninyo ako kung natapos [itong 16th Congress] at ‘di nakapasa (I promised this during the 16th Congress. You can hang me if [the 16th Congress] ends and it has not been passed),” Belmonte said then.

Road bumps

What is keeping the House from passing the FOI bill?

Advocates and legislators cited at least two things: contentious provisions such as the right of reply, and the absence of marching orders from the president.

The right of reply has become a subject of controversy since it will give people the right to respond to alleged false accusations. The consolidated version which has been pending before the Committee on Rules since May 2015 does not include a right of reply.

At least 3 separate right of reply bills are pending before the committee.

Meanwhile, Aquino took a wait-and-see approach in his first years as president and kept silent on the pro-transparency measure in his State of the Nation Addresses (SONA). After all, he said, he could not certify the bill as urgent, as there is no emergency need for it.

While the outgoing president remained silent about FOI bill up to his final SONA, he included it in his priority bills in his final budget message in 2015, issued a day after the SONA.

Did his endorsement come a little too late?

An urgent stamp would have allowed lawmakers to approve the bill on 2nd reading and 3rd reading on the same day, instead of having to wait for 3 days as provided under the House rules.

‘Death’ of FOI

The FOI bill lost its chance of passage in the 16th Congress when the House adjourned on Monday, June 6, four days ahead of the end of session scheduled on June 10.

The measure was up for approval on second reading when the House adjourned.

President-elect Rodrigo Duterte had said that if Congress would continue to drag its feet on the FOI bill, he will issue an Executive Order (EO) with the same effect once he assumes office. But the EO would only cover the executive department.

At least 95 countries have FOI laws in place. Will the country finally be added to this list under the Duterte presidency?

We have 6 years to find out. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.