SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Writing is a dangerous affair. By putting our thoughts into paper or by placing them online, we reveal portions of ourselves which we may not even care to admit.

Writing is a dangerous affair. By putting our thoughts into paper or by placing them online, we reveal portions of ourselves which we may not even care to admit.

There is in fact a reason why we write during our most intimate moments, when we are most alone—because writing is an act of self-dialogue, with the words that we use being determined (by and large) by the very character of our soul. We may present an idealized version of ourselves or set ourselves in a positive light; we may try to evade the obvious facts and even tell a barefaced lie, but the truth, which we try hard to conceal, will eventually seep out from the minutiae crevices in our narrative.

It is for this reason why we agree with Henry David Thoreau when he described the written word as “the choicest of relics” and the most directly personal of all the arts for it is “carved out of the breath of life itself.” And writing, as Trotsky remarks, always leaves its scars in print, as it exposes one’s self to ridicule, opprobrium and unyielding public scrutiny.

Through the written word, we stand naked before the world.

These were the thoughts that made the deepest impressions as we read through some of the personal accounts of two of the most important personalities from the Martial Law period.

In her Rappler article posted last September 18, Marites Dañguilan Vitug shared a few excerpts from Ferdinand Marcos’ diary entries a year before and shorty after the declaration of Martial Law.

Read: The Marcos Diary: At the heart of a dictator

On September 18, 1971 for instance, Marcos noted how the communist movement has successfully infiltrated the mainstream media, adding that, “with the possible exception of Bulletin and Herald, they (the press) are still hewing to the communist and radical propaganda line.”

By the following day, Marcos defended the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, stating that the decision was “aimed at legal cadres” who are “to be neutralized by incarceration until the danger is over.”

A year later, on September 22, Marcos wrote that, “Sec. Juan Ponce Enrile was ambushed near Wack Wack at about 8:00 PM tonight,” and then concluded his entry with the following chilling words: “This makes the martial law proclamation a necessity.”

From his entries, one can see Marcos stoking the fear of a communist takeover, while presenting himself as the only person capable of saving the Republic. But while Marcos’ diary may have been intended as a tool for image-building, his entries incidentally reveal his realist conception of power and his sheer lack of tolerance for dissent, stating that the leftwing opposition must be “shattered before they become stronger.” His entries also underscore his preferred approach in dealing with communists, “through standard military fashion—with force,” as he bluntly puts it.

This is in marked contrast with that of student activist Leandro Alejandro who offers a softer and more humane approach to power. Elected as University Student Council (USC) president of UP-Diliman in 1983, Lean was eventually arrested in February 1985 for intervening in behalf of protesters who were being dispersed by anti-riot policemen. He would then spend the next two months in Fort Bonifacio reading Tolkien and almost every possible book that he could lay his hands on.

While in detention, Lean wrote a two-page typewritten letter to his former mentor Prof. Rita Estrada of the UP-Psychology Department, which describes the conditions of his incarceration. First expressing elation that his jailers have finally “allowed us to bring in a few appliances,” Lean’s letter suddenly shifts its focus on the Marcos dictatorship and how it “humiliates our people” by subjecting them to “dehumanization, denial and death.” But unlike most prison letters, Lean’s missive has no hint of anger or bitterness, emphasizing instead that, “we must never utilize the cruel and barbaric methods of tyranny,” and that we must “fight like men, and not dogs or rats.”

Lean, however, was neither naïve nor overly idealistic. In fact, he was perfectly aware of the need to accumulate power and of eventually using it for the benefit of our people once the struggle against Marcos has been decisively won.

But Lean also cautions his comrades to exercise power “with reason, pity and understanding” for it is only by doing so “could the new power stand a better chance of not getting corrupted by their own dominance.”

Pity, we reckon, is so central in Lean’s conception of power that he even quoted a line from Gandalf the Grey as he reproached Frodo Baggins for wishing Gollum’s death:

“Pity? It was pity that stayed Bilbo’s hand. Many that live deserve death. Some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them, Frodo? Do not be too eager to deal out death in judgment. Even the very wise cannot see all ends…The pity of Bilbo may rule the fate of many.”

For Lean, power was not about command or control over people. Rather, it was the ability to convince an entire people to embark on a grand adventure so that they may attain justice and experience the widest latitude of freedom possible.

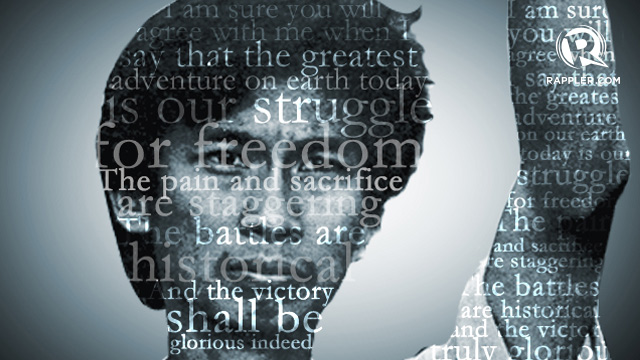

“I am sure you will agree with me,” Lean muses in his letter, “when I say that the greatest adventure on earth today is our struggle for freedom. The pain and the sacrifice are staggering. The battles are historical. And the victory shall be truly glorious indeed.”

That was quintessential Lean—a youth 25-year old activist who, for all his Marxist rigor and exacting analysis was able to appreciate Tolkien and appreciate him unabashedly.

Here, we read two figures of Martial Law with a stark contrast on their attitude towards writing. On the one hand, we have Marcos who (sounding delusional and defensive even—to himself) was “writing for history.” He was writing a piece of propaganda that tries to convince his readers that it was not greed that motivated him to declare Martial Law, but that he was in fact animated by something greater—the desire to “to save the Republic.”

It is the saddest of sadness and the hardest of falls when people have lied so much, have compromised so much, and have given up every shred of their principle they once had that they end up losing not only their soul, but their grasp of reality as well. We see that person in the diary of Marcos.

Marcos saw things the way he wanted to see them, his idealized notion of himself included. As he was trying to write his own propaganda, he lied even more, compromised even more, and trampled upon his own principles even more. And as a dictator, he soon found himself killing people, hurting families, stealing dreams, wrecking institutions and destroying an entire nation.

In contrast, Lean wrote with a deep sense of reflection. It was nuanced, honest, reflective of the complicated emotions that one goes through in such a situation—someone who would be afraid, yet would convince himself to be strong; someone who would be tempted to despair and anger, yet would seek in his heart the empathy to care even for the very person deserving only of hate; someone who would be sad, yet would choose to speak only of hope to give the rest a reason to be hopeful.

Lean’s letter was a reflection: a gaze at the mirror to see oneself truthfully and completely.

And as Lean looked at that mirror, he saw a brave little hobbit waving his fist in defiance against the looming Marcosian shadow of the Dark Lord. Such honest bravery did not only embolden the spirit of his peers and friends who were fighting the dictatorship, it also continues to inspires all of us all to face even the darkest of enemies in our own time.

And that,” as Gandalf so cheerfully remarks, “is an encouraging thought.” – Rappler.com

Joy Aceron is program director in Ateneo School of Government directing Political Democracy and Reforms (PODER) and Government Watch (G-Watch). Francis Isaac is a researcher for the Jesse M. Robredo Institute of Governance of De La Salle University (DLSU). They both love Tolkien and staunchly oppose dictatorship.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.