SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

BENGUET, Philippines – Can we detect and prevent an impending food crisis?

In its early stage, the answer is yes, through an Early Warning System for Hunger and Food Insecurity (EWS-HFI).

EWS-HFI “aims to provide information that will contribute to the analysis of causes and associated factors concerning hunger and food insecurity so that the concerned local government units (LGU) can adopt necessary preventive measures,” Dr Demetria Bongga explained recently.

The system is a joint project between the World Food Programme (WFP) and the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), in which Bongga serves as a consultant.

Its goal is to identify and analyze the causes and associated factors of hunger and food security in any given location.

This information can then be used by LGUs in creating “timely interventions.” This can also guide LGUs in setting their priorities, budget, and resources.

Where does it work?

EWS-HFI was launched in mid-2013, following the success of an EWS on food and nutrition security launched by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Ragay, Camarines Sur in 2011.

Data gathering and monitoring are done every quarter through the support of WFP and DSWD, but after a year, LGUs are expected to sustain the system on their own.

Atok, Beguet and Upi, Maguindanao were chosen as pilot sites because of their “vulnerability to impending disasters.” Atok is prone to landslides during the rainy season, while Upi experiences drought during the dry season. (READ: How climate change affects food security)

These two also have high poverty rates, with more people vulnerable to food insecurity.

The usual temperature in Atok is around 17 degrees Celcius, but it can go lower. Earlier this year, Benguet farmers lost crops to frost as temperatures went down to 9 degrees Celcius.

Atok farmers were also badly affected, according to Bongga. (READ: PH agriculture 101)

How does it work?

Teams were formed in each municipality; composed of local chief executives, LGU officials, local health and social workers.

Together, they identified the factors impacting food security.

Surveys are done by a subgroup – a team of two barangay health workers and one midwife. Teams go around barangays, interviewing families about their hunger experiences, problems and coping strategies, and diets.

In Atok, 5 barangays were surveyed by 5 teams. Each team covered 19 households with children under 5 years old. Meanwhile, 6 barangays were covered in Upi.

Relevant environmental data are also gathered: rainfall, temperature, typhoon damage to agriculture and fisheries, and environmental effects on food production.

Total agricultural production and prices are monitored. This helps track how many households have physical and economic access to food.

Lastly, the system measures household food security, diet diversity, and children’s nutritional status.

Teams use tablet computers for the surveys. Data is processed through a software initially developed by FAO.

LGUs are first trained in using the software, in data collection and analysis, according to Juanito Berja, WFP focal person on EWS-FHI.

Initial results

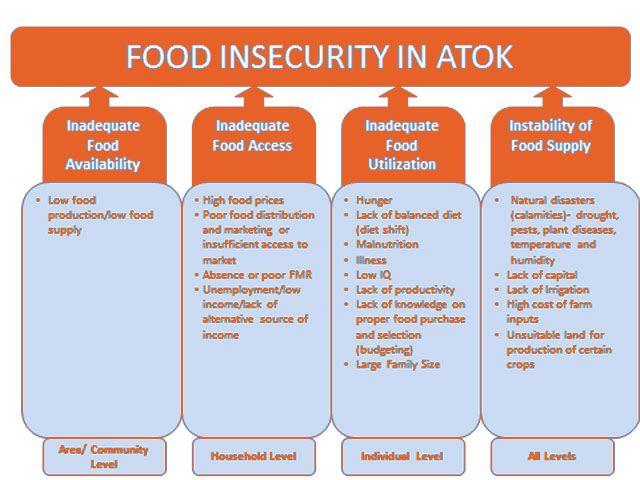

The team found that Atok experiences problems in all 4 dimensions of food security.

Some families were unaware not only of proper food preparation, but also budgeting. (INGORAPHIC: Junk food vs Good food)

From July to September 2013, the amount of rainfall in Atok was above average. But from October 2013 to March 2014, rainfall was very low and signaled a “critical alert status.” The same trend was observed in temperatures.

“The EWS team needs to sit down together to analyze all these indicators. We have to interpret the relationship of all these to the 4 dimensions of food security. Then we identify where the problem lies,” Bongga said.

By the end of 2013, vegetable production was below average, but increased at the onset of

All throughout the 8 months, household diet diversity remained critical. The diet of Atok families are “mainly energy food or carbohydrates, they lack protein and vitamin-rich food,” the EWS team found. (READ: Proper diet for elderly Pinoys)

Lessons

The initial report clarified that being “food secure” not only means eating 3 times a day, but “eating enough food for the day with enough nutrition.”

Although only less than 10% of Atok’s children aged 5 and below were underweight, stunting among children was labelled “critical” at more than 25%.

“It was an eye-opener for us,” Emilia Cuevas, an LGU midwife, said in Ilocano. “We were unaware of some of these factors, especially among children.”

Data collection in Atok began in July 2013, and Upi followed suit in October 2013. A final report is expected to be completed before 2014 ends.

“The long-term goal is to replicate these pilot programs nationwide,” Richel dela Cruz, DSWD focal person on EWS-HFI, said. – Rappler.com

How do we help fight hunger, its causes, and effects? Report what your LGU is doing, recommend NGOs, or suggest creative solutions. Send your stories, ideas, research and video materials to move.ph@rappler.com. Be part of the #HungerProject.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.