SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

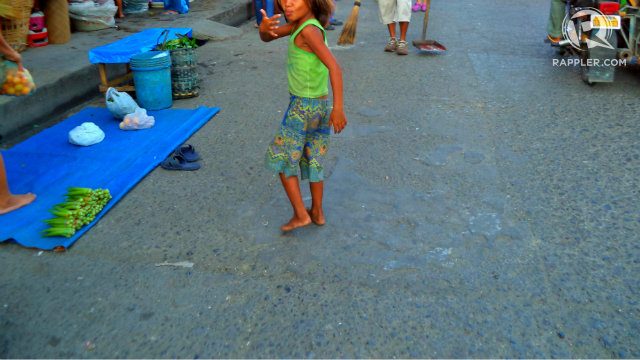

MANILA, Philippines – On April 12, the world celebrates the International Day for Street Children.

Why celebrate?

It has been recognized since 2011, but celebrations have mostly been confined to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and child’s rights advocates. April 12 just doesn’t have as much followers as holidays represented by fictional characters like the Easter Bunny, Santa Claus, and Cupid.

Advocates are hoping to change that. The annual celebration calls on governments and citizens to closely listen not only to the needs, but also the stories and aspirations, of these children.

To break society’s silence, myths surrounding “street-connected children” should be busted.

The Consortium for Street Children (CSC), an international network of advocates, came up with a list of the most common misconceptions on “children in street situations.” Meanwhile, our very own National Council of Social Development (NCSD), a network of social service agencies and NGOs, explained these myths in the Philippine context.

Did you also fall for these myths?

THE STREETS

Myth: All street children live in the streets.

Buster: Despite the Philippines being home to several street children, many of us remain clueless about who they really are. Some children live in the streets, on improvised beds, or makeshift homes along street corners and bridges.

But other children actually have homes and families, but spend huge chunks of their lives on the streets or other public places — begging, working, or “hanging out” with friends.

THE FAMILY

Myth: All street children come from broken or dysfunctional families.

Buster: Each child’s situation is different. Some of them may come from families dealing with issues of death, dislocation, isolation, poverty, mental illness, domestic violence, child abuse, drug use, among others.

The CSC, however, stressed how these families have also been affected by society’s “heightened inequalities and inadequate social protection.” Some children have also been separated from their families due to armed conflict or disasters.

Other children, however, belong to non-abusive families. They opt to be out in the streets for survival, the NCSD observed. These children work so they can help their parents, or simply because they need to eat. In short, not all of them come from “bad” families.

Aside from factors pushing children to streets, the CSC also identified factors “pulling” children to stay: enticements of apparent freedom, independence, or adventure, friendships, city glamor.

THE NUMBER

Myth: The world has 100 million street children.

Buster: This estimate was made by UNICEF in 2005. Until today, not all cases are documented.

“Counting street children can be difficult because they may not want to be found, may be frightened or mistrustful of authorities, may not be known as ‘street children,’ or may not have a fixed place to live,” the CSC said.

In the Philippines, official government statistics show there are 246,011 street children. This is 3% of the youth population aged 0 to 17. However, this was estimated way back in 2001. The latest statistics from the Department of Social Welfare and Development reveal there have been over 3,000 street kids in Manila as of 2010.

Some of them are also victims of abuse: physical, sexual, trafficking, exploitation, child labor. And some get caught up with crimes.

These are children, not just numbers, that go up and down.

EXISTENCE

Myth: Street children exist only in poor areas.

Buster: They are everywhere, even in rich countries or “developed” cities. However, the CSC observed a higher number of reported cases in countries and regions with high social and economic inequalities.

These girls and boys are not only found in the National Capital Region, but across all regions. Not just in urban cities, but also in rural areas.

INCAPABLE

Myth: Street children are victims.

Buster: While it is true that many street children may have been exposed to different forms of abuse and injustice from an early age, advocates say they should not be viewed as powerless victims.

Instead, advocates encourage governments to empower these children by providing adequate and long-term solutions, while also recognizing their strengths.

And don’t forget: They are just like any other kid; they have dreams, talents and skills, hobbies, quirks, and individual stories. They do not lack capabilities; what most of them lack are opportunities.

BAD KIDS

Myth: All street children are criminals or druggies.

Buster: The CSC stressed how street children may have been pushed to do all sorts of things in the name of survival. Some were forced by others, some were forced by the desire to live. In the Philippines, NGOs observe that many children “get high” to numb themselves from hunger.

“In criminalizing survival behaviors or not taking into account the reasons behind a child’s involvement in criminal activities, society stigmatizes and isolates street children,” the CSC added.

They deserve help and rehabilitation.

Some of them study, some don’t. Some go to school in the mornings or in the afternoons; when not in school, they are out in the streets.

The CSC observed that some street children may “struggle in integrating in standard education programs,” since they mostly live transient lives, lack family support, and juggle studies alongside work and other obligations. Many cannot afford school, they may also be discriminated against by classmates. Hence, the CSC advises governments to come up with “tailored and specialized interventions” addressing the diverse and complex situations of street children.

The NCSD also argues against penalizing parents of street children, calling it a “wrong approach which would further add to the criminalization of street families,” without addressing the problems that led to the neglect or abandonment of children.

To break the cycle, punishment may not be the most effective solution, advocates say. Empowering and educating the parents would be more helpful, NSCD suggests, enabling them to care and provide for their children.

Although they are present in our daily lives, street children have mostly stayed in our peripheral vision – an afterthought, a side project, a statistic. And for some, a myth.

Ignorance makes indifference easy, and indifference normalizes ignorance. It is a vicious cycle trapping many of us, even the good ones. – Rappler.com

To get in touch with various children’s organizations, you may reach the National Council of Social Development at 353-8466 or ncsdphils@yahoo.com.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.