SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – In commemoration of the dark years of martial law, declared on September 21, 1972, we are running excerpts from the book Subversive Lives: A Family Memoir of the Marcos Years edited by Susan F. Quimpo and Nathan Gilbert Quimpo.

“P___ ina,” I swore repeatedly as I fumbled with my camera lens. I peered into the viewfinder, it was cloudy. “Don’t fail me now!” I quietly chastised the equipment and, desperate to clear my view, rubbed its lens with the helm of my shirt. Again, I pressed the viewfinder against my eye, its rim was moist. There was nothing wrong with the camera. I just could not focus; there were tears in my eyes.

September 25, 1984 – the day started innocently enough. It was a dry, hot day, dust clouds rose from the jeepney’s tires as it maneuvered the Angono-Cainta route. It was unfortunate that my cousin Candy Quimpo could not borrow her father’s car. To get to the suburban steel factory meant taking two jeepney rides for two hours and needing two, scarf-sized handkerchiefs to protect one’s face from the billowing dust.

For weeks, Candy and I were planning to shoot a short amateur film about the factory strike at the 10-hectare compound of Globe Steel Incorporated. Candy and I were in our early twenties, a couple of freelance writers who met while working for a children’s television show.

That warm September morning, we planned on taking still pictures of the strike area in preparation for the film. We arrived an hour or two before the noonday sun would be too harsh for our pictures. The workers and their wives welcomed us like old friends. Candy showed photographs of the workers she had taken during a recent protest march. The mood was jubilant despite the dire consequences brought about by the strike.

It had been nearly three months since the Globe Steel workers heeded the call for a “work stoppage.” At three in the morning, the evening shift laid down their tools and walked away from their assigned posts. For the first time in its 25 years of existence, the steel mill was quiet and void of the human energy that operated its 10- and 15-ton smelters.

Globe Steel’s management favored employing migrant workers from Bicol and the Visayas. Desperate for jobs, these workers and their families lived in squalid shantytowns that dotted Metro Manila. They were only too eager to trade their manual labor for less than the minimum wage. Globe Steel workers were hired as “casuals” whose contracts were renewed every six months. It was not unusual for workers to still be on the casual payroll even after five years of continued service. On their first day of the job, workers were asked to sign a blank sheet of paper. And in the future, should the worker be a source of “trouble,” the signed document would re-surface with a “letter of resignation” appearing above the employee’s signature.

Management sought mostly illiterate workers; those with a high school diploma were considered “overqualified.” It was common among the manufacturing industries to hire workers from Manila’s slum districts. The truism – the less educated and the more marginalized, the less likely to organize and protest – was one management adhered to.

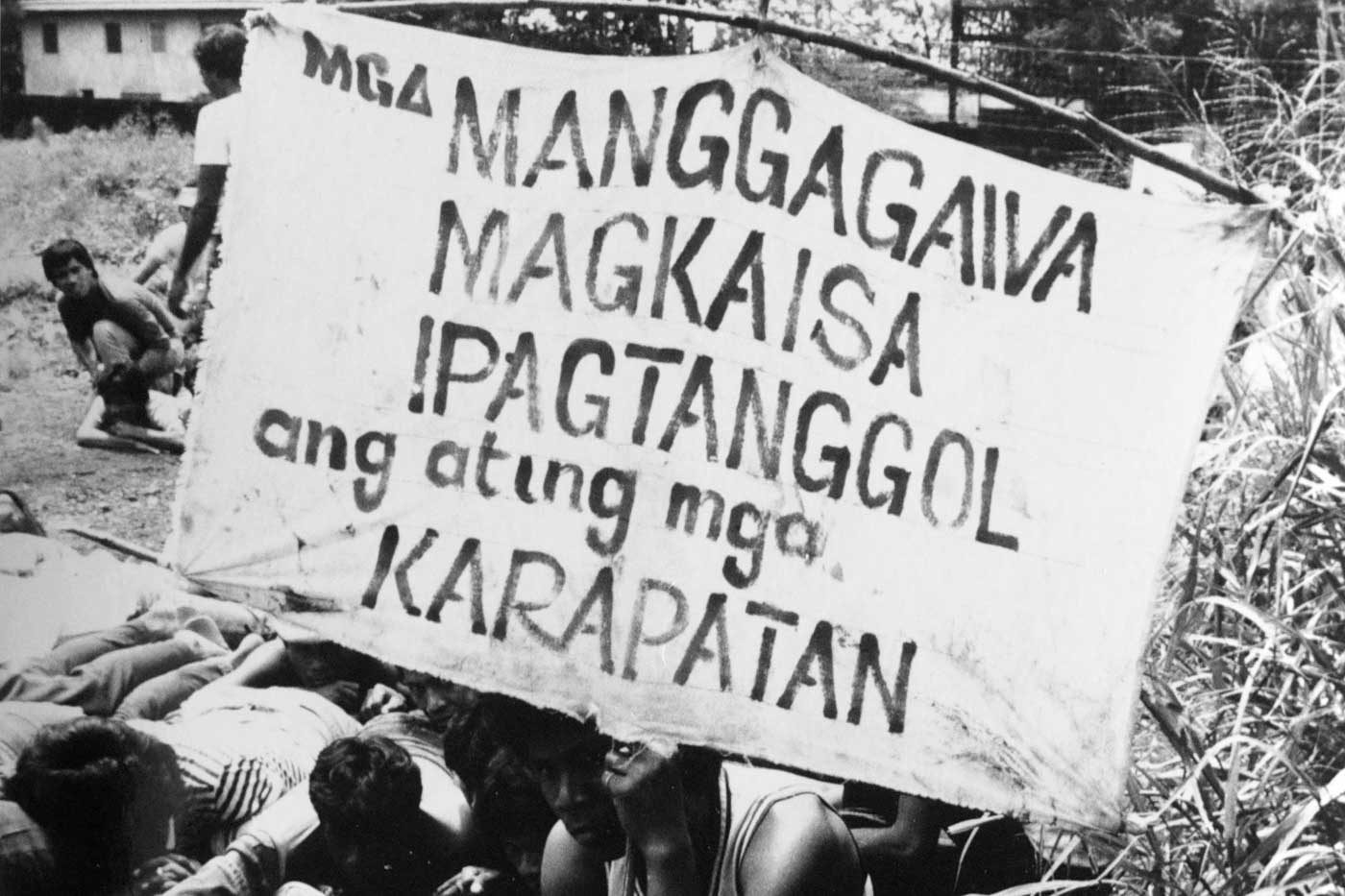

But at Globe Steel, even the most docile of employees were fully aware of their exploitation. Labor organizers affiliated with the most militant of Manila’s labor unions joined the ranks of the steel workers. Skilled and experienced, the organizers soon had the workers demanding a union that would press for fairer conditions. Management refused and terminated the would-be officers. On June 27, armed only with resolve, 528 workers had walked past the baffled security guards and out the factory gates to begin a long and tenacious battle for their rights.

Unable to afford rent, the workers and their families erected shelters of cardboard and scrap wood outside the factory walls. A large canvas tent stretched over bamboo poles became the “new union headquarters.” Without wages, the workers had to forego even the barest necessities. Their families were dressed in rags; malnutrition was evident in pot-bellied children with gaunt limbs. The wild cogon grass that flourished on the sides of the road leading to the factory was cleared to make room for kangkong. Food was scarce and potable water unavailable. On our first visit, the workers graciously offered us lunch. They said we had picked a special day to visit – for once they had meat which they readily served. Candy and I later learned that they had found a dog that died from an infection and its carcass had been made into stew.

But today, as usual, the workers were in high spirits, smiling sheepishly as their wives scrutinized Candy’s pictures.

“Mga truck, mga truck!” an alarmed voice interrupted the women’s cajoling. A convoy of seven trucks with a delivery of raw materials for the steel mills was spotted headed for the factory gates. Some of the trucks bore human cargo – scabs. Escorting the trucks were jeeps and small buses of nearly 200 armed personnel in Philippine Constabulary uniforms. The trucks stopped about 50 meters from the factory gate, their drivers awaiting further orders from their military escorts.

As protest mounted against the state’s anti-labor laws, it became common to use the police and military to break picketlines to protect “vital industries.” Eventually, it became apparent that all industries were vital to national interests, and that all strikes, though often warranted, were in effect, illegal.

The union officials pleaded with the PC Lieutenant in charge of the troops. The other workers knew it was futile. “They will use force,” one of the workers cautioned.

Candy handed me one of her press IDs, one that did not have her picture; I fastened it conspicuously on my chest. It was a ritual we often repeated when confronted with potential trouble with the police. Though it was no guarantee, we hoped that press cards would help deter injury or arrest. With our cameras cradled in our hands, we took our positions.

It was then I heard women sobbing softly, almost inaudibly. The boisterous sound of the truck mufflers drowned out everything else. A curious sight was unfolding before me, first filling me with awe, then horror as I grasped its full intensity. In trickles, men and women laid their bodies on the asphalt road, hugging the dust in front of the first truck. “Do not retaliate, do not fight back,” they repeated amongst themselves.

In quiet defiance, they formed three barricades, three lines of human flesh. The women formed the first blockage, scorning the machismo of the men in uniform. A woman with salt-and-pepper hair had suspended herself from the truck’s fender, positioning her head close to one of its front wheels.

“I have only one child,” she cried. “You are killing us slowly with hunger. It is better that you kill me now, it will be a quick death. Go ahead,” she continued between sobs, “order the driver to start your trucks!” Inspired by her courage, more women left their toddlers at the wayside to join the barricade.

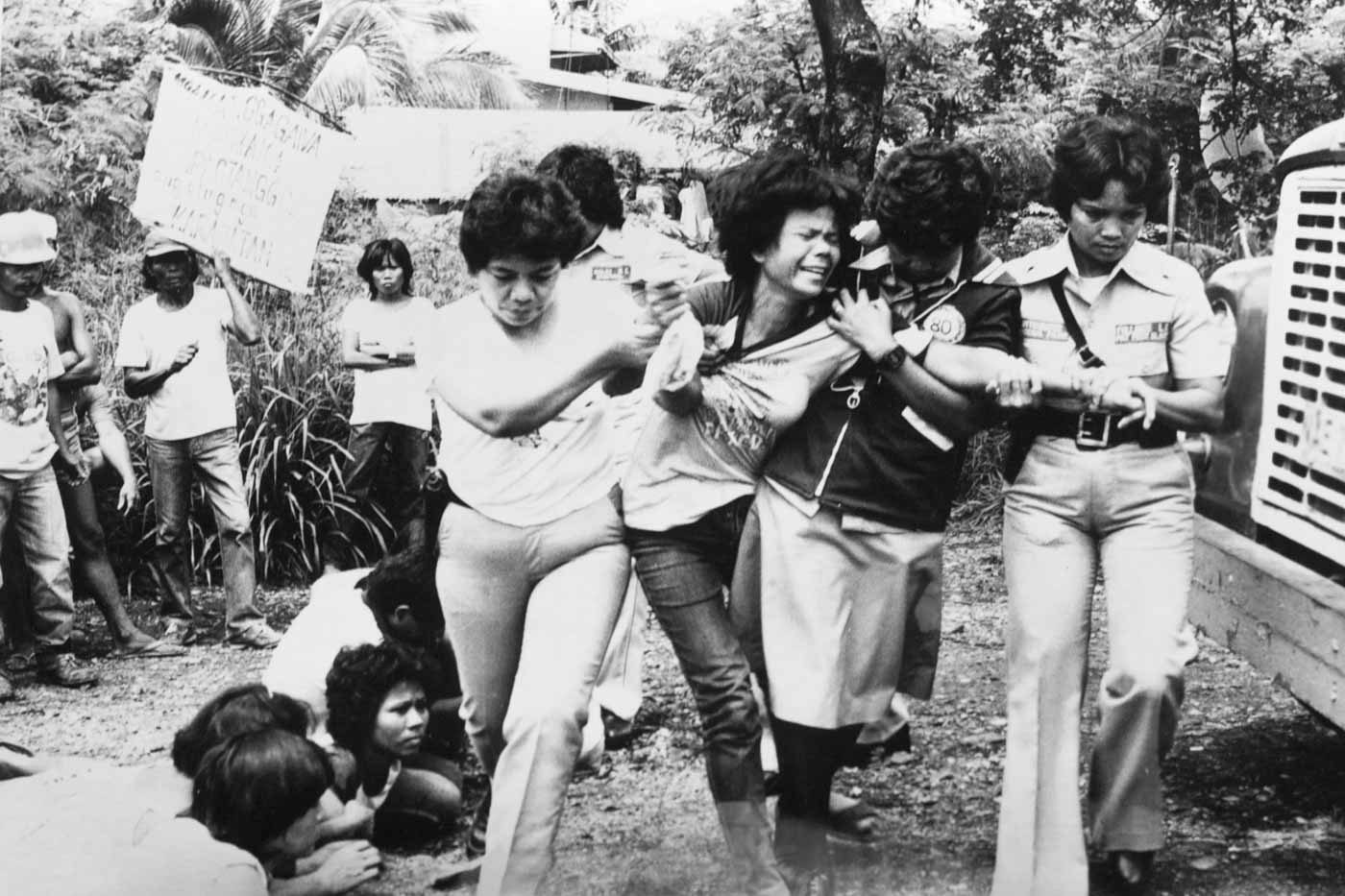

The PC lieutenant seemed unnerved. He convened with a few of his men, a courier was dispatched and within minutes, a number of policewomen were summoned. The workers’ wives were dragged away from the barricades while the PC’s sneered victoriously. From the ranks of the policemen who ogled the arrests, I overheard, “I’ll take than one, yes, that young woman!”

“Kapitbisig!” Link arms. The men on the ground, forming the second barricade, steeled themselves. The police responded by forming a single file, brandishing metal shields in front of them. They moved forward toward the human barricade, aligning their shields like a solid wall, pressing the steel frames close against the workers heads. A steady thud emanated from behind those shields, like the sound of hammers on metal sheets.

“He’s bleeding!” gasped a bystander. Blood was trickling down a worker’s forehead, staining the shield pressed against his face. By then it was apparent, the steady thud I heard were truncheons, solid batons that the police hammered against the shields, hitting heads with doubled potency.

As the workers weakened and the police hauled them away by their waistbands; but comrades took their vacated spot on the asphalt road. The human barricade was holding for it seemed there was no lack of volunteers eager to take the blows. Frustration was etched on the policemen’s faces, and tempers rose, overpowering their restraint.

Truncheons, now without the camouflage of metal shields, struck heads and shoulders with full severity. Some truncheons were laced with barbed wire, causing the skin to rip on contact. At the corner of my eye, I saw electric sparks searing the arms of the workers. Later I learned, the police used cattle prods that emitted charges potent enough to burn human flesh, potent enough to break the hold of human arms linked in a common struggle.

That was when I realized I was weeping, overwhelmed by the flagrant brutality displayed before me. I fumbled with my camera, unable to take more pictures.

“Miss, take cover, now!” a worker whispered in my ear as he attempted to pull me away from the melee. I was surrounded by truncheon-wielding cops bashing the shriveling bodies that lay at my feet. The noonday sun was in my eyes, metal shields, swinging sticks, ripped shirts on sweat-drenched bodies, sipped skin. A collective moan rose as the truncheons fell with increased frequency. “Stop, stop. Enough, please!” I muttered as I slowly retreated fully expecting a blow to my head.

A hail of stones

In a split second, a hail of huge stones descended, hurled from both sides of the road and aimed at the men in uniform. The laborers’ wives and children who initially stood inert broke their vow of passive resistance. Horror was replaced by anger and fists were unclenched to grab and hurl stones barely missing my face. I sank knee-deep in mud, protected by sharp sheaths of cogon, thankful for my temporary refuge.

“Candy!” my thoughts raced wildly as I distanced myself from the police who were scampering toward the factory gates warding off the barrage of stones with their shields. Her journalist instincts served Candy well; she was a safe distance away from the fracas among the reserve police corps.

I waddled through the mud toward Candy. She displayed the calm yet near-arrogant air of authority, a façade that journalists used as a measure of protection from the irreverent police. Candy’s face softened with relief when I emerged from the paddy, distraught, dirty buy unscathed.

“Are you okay?” she asked.

I nodded. “Where were you?”

“I got out before the stoning started. I’m out of film,” she said. We expected our visit to the factory to be uneventful and it did not occur to us to carry spare rolls of film.

“Here, I have about six shots left. You’re bound to take better pictures,” I replied, handing Candy my camera, deferring to her experience.

Strange hollow, popping sounds suddenly emanated from the factory gates. The police reserve corps dropped their mocking stares and assumed defensive positions behind their military jeeps.

“What was that?” Candy surveyed the gates.

“Gunfire!” I answered, again feeling the panic swell inside me.

“They have guns! They have guns!” cried a policeman pointing to a clutch of women and children nursing their wounded kin. I drew my gaze in the direction he was pointing to and saw women and children armed only with stones. The only guns I spotted were those in the hands of men in uniform.

At that point I felt a body brush against me and instinctively I stepped aside. A stocky man from the ranks of the police had stepped right in front of us and, with tenacity, drew his revolver from his black leather holster. With his arm straight and steady, he aimed at a fleeing worker then pulled the trigger, thrice.

“Candy!” I signaled my cousin to take the man’s picture. She already did. Still with the pistol in his hand, the man turned toward us. He then realized that a camera had documented his deliberate aim. He grimaced and sought a quick exit.

The man’s arrogance and conscious disregard for human life triggered something within me. I grew up hearing words like “state fascism, police brutality, dictatorship…” said in hushed tones during clandestine meetings and later incorporated into angry chants and slogans repeated at protest rallies. Torture and illegal imprisonment, stories of summary executions and the disappearances of student and labor leaders – all the abuses of the state were made possible by men like this who could, without flinching, take deliberate aim and fire at unarmed civilians. At that particular moment, the cries and advocacy of “Rebolusyon!” had made perfect sense; indeed, there seemed no other recourse in a country so visibly militarized. The graphic scenes I witnessed that afternoon had been unprecedented in my experience – these affixed a hard face on oppression. I felt I had to do something.

“Hey, you…wait!” I was at the man’s heels quite unsure of what I was doing. I caught up with the man, grabbed him by his collar and shook him repeatedly. I glanced at his nameplate, “Diaz,” it read.

“Diaz! Diaz, so that’s your name! Those weren’t warning shots you fired back there… you took direct aim. You were firing directly at that worker; we have pictures to prove it! You’ll see your pictures in the papers!” I loudly admonished him, my grip tightening around his collar, forcing him to face me. I was trembling, my words delivered in choking phrases. But I correctly gambled that Patrolman Diaz would be too stunned upon hearing my colegiala English, that he would be unable to respond or hurt me.

Candy was pulling my sleeve. “Susan, stop it. Let it go!” she pleaded. The man still had his revolver in his right hand and the impetuous scowl on his face. I expected him to pull the trigger on me and, for a moment, I didn’t care. I was more upset than afraid. Candy dragged me away from the scene while Diaz disappeared into the crowd.

The barricade had been broken. Candy and I watched all seven trucks roll through the factory gates amidst the cheers of the military.

Twelve workers were seriously hurt that afternoon. Their friends and family brought them to the Angono General Hospital for treatment. There they were met by members of the same PC battalion. The military waited until the strikers received medical treatment then arrested them for “direct assault on persons of authority.” That same evening, these strikers were mauled by their arresting officers.

The following morning, the remaining workers were back at their picketline restoring the tent that covered their makeshift headquarters. The Globe Steel strike would hold strong for four years making it the longest worker’s strike in Philippine history.

I kept my promise to Patrolman Diaz. His picture – scowl, gun and all, together with our other pictures of the strikebust, had made to the papers.

– Rappler.com

All photos by Susan F. Quimpo

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[PODCAST] Beyond the Stories: Ang milyon-milyong kontrata ng F2 Logistics mula sa Comelec](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/11/newsbreak-beyond-the-stories-square-with-topic-comelec.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[EDITORIAL] Ang low-intensity warfare ni Marcos kung saan attack dog na ang First Lady](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/animated-liza-marcos-sara-duterte-feud-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=294px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Free to disagree] How to be a cult leader or a demagogue president](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/TL-free-to-disagree.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Can Marcos survive a voters’ revolt in 2025?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-voters-revolt-04042024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=251px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Edgewise] Quo vadis, Quiboloy?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/quo-vadis-quiboloy-march-21-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.