SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

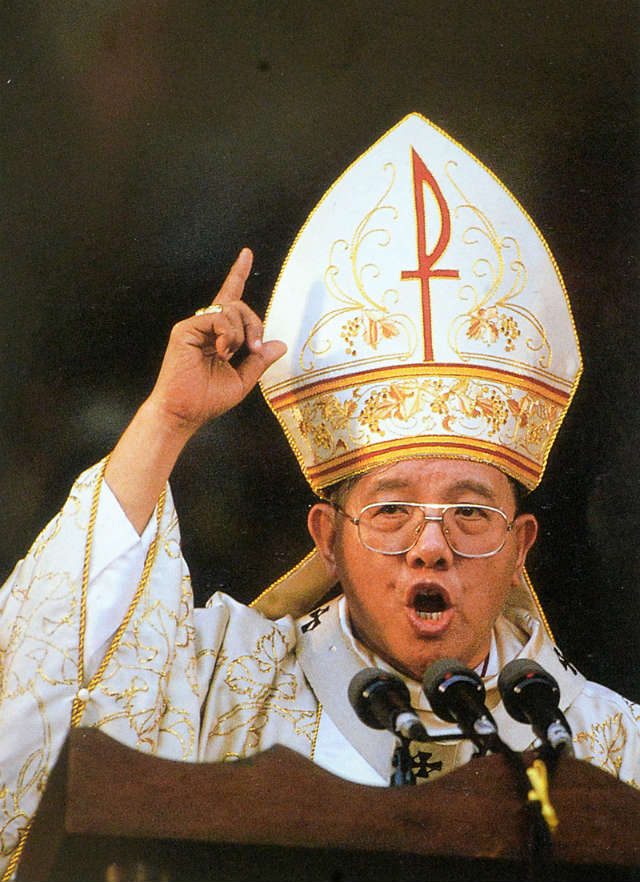

MANILA, Philippines – The Catholic Church in the Philippines lost its single most powerful voice on June 21, 2005, after former Manila Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin died of renal failure at the age of 76.

Father Xavier Alpasa, head of the Jesuit sociopolitical group Simbahang Lingkod ng Bayan (SLB), recalled a widespread sentiment shortly after Sin’s death: “Nawala na si Cardinal Sin. Wala nang magsasalita (Cardinal Sin is gone. No one will speak anymore).”

Sin was best known for helping topple dictator Ferdinand Marcos on February 25, 1986, after he urged Filipinos to troop to the main highway EDSA to protect rebel forces.

His appeal over the Catholic Church-run Radio Veritas prompted the bloodless EDSA People Power Revolution, which marked its 30th anniversary this year. (READ: EDSA: ‘Hand of God’ seen from the House of Sin)

More than a decade after the rebellion of 1986, the cardinal backed another popular uprising that ousted actor-turned-president Joseph Estrada on January 20, 2001, over corruption charges.

Sin also clashed with the government over birth control and a proposal to revise the Constitution.

With the death of Sin in 2005, Alpasa said that on the one hand, many Catholics felt they lost a “guidepost.”

On the other hand, he said, it became a challenge for Catholics to galvanize their “shared” power – for it to become “real People Power and not just a Cardinal Sin power.”

‘Cardinal Sin dared to talk’

This “Cardinal Sin power,” after all, emerged from a different context.

Sin’s long-time private secretary, Lingayen-Dagupan Archbishop Socrates Villegas, said the cardinal first challenged Marcos a time when “people were afraid to talk.”

“But Cardinal Sin dared to talk,” Villegas said in an interview with Rappler.

Born in Aklan, Sin became archbishop of Manila in 1974, when the Philippines was under martial law.

Marcos had imposed military rule in 1972 and lifted it only in 1981, though the abuses continued.

It was a time of warrantless arrests and forced disappearances. Amnesty International said 70,000 people were imprisoned, 34,000 were tortured, and 3,240 were killed during the martial law years. (WATCH: What if martial law were still in effect today?)

Villegas said Marcos, however, “knew that it would be foolish of him to attack the Church or to destroy the Church, because the Church is a respected institution.” This is why Marcos “wanted to get the favor of the Church all the time.”

Villegas said Sin used this situation “to speak against the abuses of the martial law years, because he knew that he would not be arrested.”

The raid that changed it all

Villegas explained that Sin, former archbishop of Jaro in Iloilo, “was very quiet” when he came to Manila.

He said Sin started criticizing Marcos after the government raided a Jesuit seminary – the Sacred Heart Novitiate in Quezon City – shortly after he became Manila archbishop in 1974.

Back then, the government suspected that there was a Marxist meeting in the novitiate. Officials then arrested a number of people there, including priests, and confiscated documents.

Villegas said this prompted Sin to issue a pastoral letter to be read in all the churches of the Archdiocese of Manila, which then covered Metro Manila and even the province of Rizal.

He added that because “some of the priests were afraid,” Sin included this order in his pastoral letter: “This must be read in full, without adding or deleting anything.” In other words, he placed his priests “under obedience.” Villegas said Sin, through his letter, was “protesting against the persecution of the Church.”

From then on, he said, “the relationship became guarded for both sides,” for the camps of Marcos and Sin.

It came to a point when Sin was even barred from leaving the Philippines for Rome, because he was placed under a “no-travel order.” (Villegas said Sin was eventually allowed to leave after the problem “reached Malacañang.”)

‘We are all the Church’

The ousting of Marcos, however, changed the landscape for the Catholic Church in the Philippines.

“Thirty years ago, if a layperson came out speaking against Marcos, tapos siya (that’s the end of him). That is why the bishop took the cudgels for these innocent people who were suffering. But now, when laypeople speak, we are assured that they will be given due process,” Villegas said.

While Sin was “a brave and needed voice” of his time, Alpasa agreed that the context is now different.

He said that after Sin’s death, “power” from Sin “naturally flowed” toward the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP), the collegial body of all bishops in the country.

The CBCP meets twice a year and issues statements on various issues affecting the Philippines, including drugs, pornography, and the election process.

“Before, people really waited for Cardinal Sin to speak. Now suddenly, there is greater interest in the CBCP pastoral statement,” Alpasa said in a mix of English and Filipino.

Alpasa pointed out another “evolution” in the Catholic Church’s role in politics.

“Dati si Cardinal Sin ‘yan, nagsasalita. At ang mga tao ay sumusunod. And then we realized, in the modern context, kailangang i-draw out, bigyan ng boses, ipaalala sa mga tao, ‘Puwede ka ring magsalita. Ikaw din ay Simbahan at hindi lang ang pari o ang kardinal. Tayong lahat, maging Simbahan. Magsalita tayo,’” the Jesuit said.

(Before, there was Cardinal Sin speaking. And the people followed. And then we realized, in the modern context, we need to draw out, give a voice, and remind the people: “You can also speak. You are also the Church, not just priests or cardinals. All of us should be the Church. Let us speak.”)

Echoing the mission of SLB, he stressed the need to put people “at the center of politics.”

Issues ‘from the ground’

Alpasa said a good example was the march of 55 farmers from Sumilao, Bukidnon, in 2007.

Back then, the farmers walked 1,700 kilometers to the Philippines’ capital, Manila, to assert their claim over a 144-hectare piece of land in the southern Philippines.

Catholic leaders – including the archbishop of Manila back then, Cardinal Gaudencio Rosales – welcomed them in the Jesuit-run Ateneo de Manila University on December 5, 2007, after their 60-day journey.

From there, the Sumilao farmers trooped to the presidential palace or Malacañang on December 6, 2007, to bring their case to then President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.

Initially barred from getting near the palace, the farmers got an audience with Arroyo on December 17, 2007.

The farmers eventually won 197 hectares of land even as they remain in debt, according to Sun.Star in September 2015.

Alpasa considers this a classic example of a grassroots movement that was backed by the Catholic Church, but did not begin with priests or religious sisters.

He said that from having “one figure” in the person of Cardinal Sin, calling for the EDSA Revolution, “it was suddenly an issue from the ground – grassroots, not priests, not nuns, but farmers – but still sacramental,” a sign of the sacred.

Alpasa said another example is the 350-kilometer march of indigenous peoples from Casiguran, Aurora, to denounce the construction of the Aurora Pacific Economic Zone and Freeport Authority (APECO).

Headed by powerful Angara political clan, APECO aims to convert more than 12,900 hectares of land into a trading agro-industrial center.

The current archbishop of Manila, Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle, joined the Casiguran farmers in their protest also in Ateneo.

On putting people at the center of politics, Alpasa said, “Nakikita kong nabubuo ‘yung mga puwersa, pero hamon pa rin siya kasi hindi pa rin siya talaga kultura ng buong Pilipinas (I can see that the forces continue to be formed, but it remains a challenge because it’s still not the culture in the whole Philippines).”

He said this remains a challenge especially as the Philippines seems to be moving backwards.

Alpasa, whose group was formally born shortly after the EDSA Revolution, pointed out the rise of vice presidential candidate Ferdinand Marcos Jr in recent surveys. (READ: Bongbong Marcos on EDSA revolt: It was politics)

“Para sa akin, indicative ‘yan na kung ano man ang gains nu’ng 1986, quite profoundly and paradoxically, remain to be a challenge because the son of the dictator is now topping the surveys for vice president (For me, it’s indicative that the gains in 1986, quite profoundly and paradoxically, remain to be a challenge because the son of the dictator is now topping the surveys for vice president).”

‘Shrewd as serpents, simple as doves’

Alpasa said the Catholic Church, then, needs to be “more discerning.”

“Palagay ko noong una, may isang maliwanag na kalaban (I think that before, there was one clear enemy),” he said, referring to Marcos.

“Palagay ko ngayon,” he continued, “mas komplikado ang sitwasyon kasi hindi na isang tao ang kalaban kundi sistema (I think that now, the situation is more complicated because the enemy is not just one person but a system).”

This system involves the dealing with millennials, harnessing technology, and generally “a more complex milieu.” The context includes a church that, in Alpasa’s words, has lost much of its clout after Sin helped topple Marcos in 1986. (READ: From EDSA to RH: Church clout weakens in PH)

Alpasa then recalled a biblical passage wherein Jesus tells his disciples to “be shrewd as serpents and simple as doves.” He said, “So the call for the Church now is to be more discerning, to be more astute, to be more immersed.”

For Alpasa, the perfect example of this is Pope Francis, who is “astute in this complex world.”

Describing the first Jesuit pontiff, Alpasa said: “He’s able to meander through very complex issues like same-sex marriage, homosexual issues, and at the same time, this issue on the environment and modernity. He can make a statement and, at the same time, be palatable.”

Villegas, for his part, also stressed that the Gospel “must be taught and preached in the realm of politics.”

“And it is not an option. It is a duty,” Villegas, now the CBCP president, said in his interview with Rappler. “It is a duty because politics without Christ would be contrary to God’s design, because the Gospel should enter every aspect of human life – culture, politics, economics, everything.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.