SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – The police found him at a little before two in the morning of Saturday, August 20. He was curled into the seat of a red tricycle, bare feet stretched past the handlebars, head tucked into the space between the motorcycle and the tarp-covered sidecar.

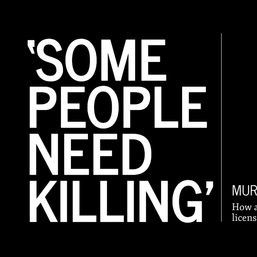

There was no cardboard sign to mark the man an addict. There were no marks on the camouflage-print cargo pants or anywhere on the bright blue shirt hiked up over his waistband. He could have been asleep, if it weren’t for the blood pooling under the back wheel and the pair of gunshot wounds at the back of his neck.

This is Tondo, population 630,363, one of Manila’s poorest, where the shanties sit cheek to jowl with slaughterhouses and churches. The residents of Parola have no name for the four-lane highway cutting through the rows of skinny mismatched townhouses plastered over with campaign posters. Maps mark it as the MICT Access Road. Six-wheeler trucks rumble past at all hours.

They found the body just across Gate 64, in Area B, lit by the dull yellow of a single streetlight.

His name was Jerome Roa, age undetermined, address uncertain. His grandmother Josephine said he may have been 27 or 28, certainly no older than thirty. He lived on the street, kept what few clothes he had in the home of an old family friend, and spent the nights in any one of the tricycles parked in haphazard lines along the sidewalks.

It was that family friend who rushed to where Jerome’s grandmother worked as a live-in cook. Jerome had been shot, Jerome might be dead, run, hurry.

Josephine ran, through the warren of twisting alleys, out through the arch of Area D, Gate 18, cutting through the highway past the police cars and the media vans and the windowless façade of Korea Truckers, where Jerome used to work. The onlookers made room for her just outside the circle of yellow tape and flashing lights.

The reporters found her eventually. She was quiet as she stood, a 67-year-old woman in a faded red shirt wiping sweat and tears with a grimy kitchen towel.

Jerome was her boy, she said. He was an addict. She had always known.

‘Couldn’t be helped’

She had raised him while his mother worked in Cebu. His father was a good-for-nothing bastard who drank what he earned. She made her daughter leave him, took Jerome under her wing, raised him as well as she could and watched him graduate from elementary school in the slums of Manila.

The drugs came with the trucking job – drugs, said Josephine, were a trucker’s medicine. It was the reason why she had never rented a room again for the two of them. Once, when they lived together, she would go to work and come home to his bad friends and their bad habits. A room of his own would mean the same thing.

But she insists Jerome had changed. In the last two months, after he lost his job at the trucker’s and found another one pushing tricycles into line, he could barely afford food, much less the cash he needed for a fix. She saw him every week, would bring him food, sometimes money.

When Rodrigo Duterte became president, the word spread that addicts would be killed. Josephine’s boss, a village councilor, told her he should surrender. Everyone knew Josephine’s grandson was on drugs. She had asked him to surrender and he refused.

He was already clean, he said. Why should he turn himself in?

‘Someone saw it happen’

Jerome’s body was gone when she walked to the tricycle. The crime scene had emptied. The cameras had been slung into media vans, the onlookers had gone home. The police had wrapped her grandson in blue tarp, then loaded the corpse into the back of a utility truck. It was too late to see his face.

She patted the torn seat where they found him. Jerome, she said, pray for us.

No witnesses have come forward. Josephine says there were people who saw what happened. She says they know who killed Jerome.

She does not expect them to speak – they are afraid, and they would be right to be afraid. They might be next.

Josephine and Jerome had plans. They were saving money – or she was, and he was trying. They were going to go home, away from Manila, to Cebu where his mother is. Now Josephine has to call his mother to tell her about her son. Maybe Jerome’s mother can come to where his body will be buried, because Josephine can’t afford to send her grandson home.

She believes it must have been the drugs that killed Jerome, because her boy didn’t have an enemy in the world. She understands what happened couldn’t have been helped.

She doesn’t have a problem with the killing, and the men who did it, if they did it because of that. All she wants to say is that Jerome was a changed man before he died.

The new normal

At a little past three in the morning of Tuesday, August 20, a 67-year-old woman named Josephine Cabalquinto ducked under a circle of yellow tape to walk past the high hollow-blocked walls lining the MICT Access Road. She put the kitchen towel on her head, crossed the street, stepped under the arc of Area D, Gate 18, and walked past the shanties, through the warren, turning corner after corner until she knocked on a padlocked door.

In the seven weeks since President Duterte was elected into office with the promise of a bloody end to the drug scourge, at least 16 people have been killed in the rough and tumble district of Tondo. According to the list published by the Philippine Daily Inquirer, three were killed by unidentified gunmen, two of whom were found with cardboard signs scrawled with “drug pusher.”

Thirteen more were killed in alleged shootouts or drug bust incidents involving the police.

They are among at least 800 killed across the country in the last two months.

Ask Josephine if she is angry. She will shake her head.

Ask the crowd of onlookers, and they will say this has happened before, more in the last few months.

Ask them if they are afraid, and they will hesitate, and then they will say no. It is not dangerous, said a young tricycle driver who knew Jerome.

You will be safe, for as long as you behave. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[EDITORIAL] Hustisya sa Jemboy case: Tinimbang ka ngunit kulang](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/animated-jemboy-baltazar-killing-verdict-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=257px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[WATCH] Dahas Project, the team that continues to count drug war victims](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/dahas-project-2.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=404px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[EDITORIAL] Sorry Arnie Teves, walang golf sa kulungan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/animated-arnie-teves-arrest-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=310px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.