SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines — “Nangako kasi ako sa mga surrenderer ko na walang mamamatay sa kanila (I promised my surrenderers that none of them will die),” Renato said one December morning in 2016 as he checked the identity of a slain man accused of peddling illegal drugs in his community.

Renato, 37, is the point person of the barangay anti-drug abuse council (BADAC) in his area. He regularly checks crime scenes in his barangay to check the identities of those killed in police operations, always hoping they’re not one of his surrenderers.

From July 1, 2016 to January 27, 2017, President Rodrigo Duterte’s campaign against illegal drugs has claimed a total of 7,063 lives, 2,538 of them killed in police operations, while 3,603 deaths are still under investigation. (READ: IN NUMBERS: The Philippines’ ‘war on drugs’)

With an average of 33 deaths per day in the drug war, Renato’s promise to his wards would seem unrealistic. But as the name of Renato’s village in Quezon City – Barangay Bagong Pag-Asa – suggests, there is “new hope” for surrenderers.

‘New hope’

Renato is running the local BADAC on his own. His task is to profile residents who are tagged by the police in the illegal drug trade, but he wanted to do more than just fill a database with dependents’ profiles.

In September 2016, Renato started a simple rehabilitation program he himself crafted. Every Saturday morning, he would gather local surrenderers at the third floor of the barangay hall to attend bible study sessions and to participate in Zumba classes.

On top of that, he is thinking of getting the surrenders TESDA training in the summer of 2017, when parents don’t have to mind their children’s schooling needs.

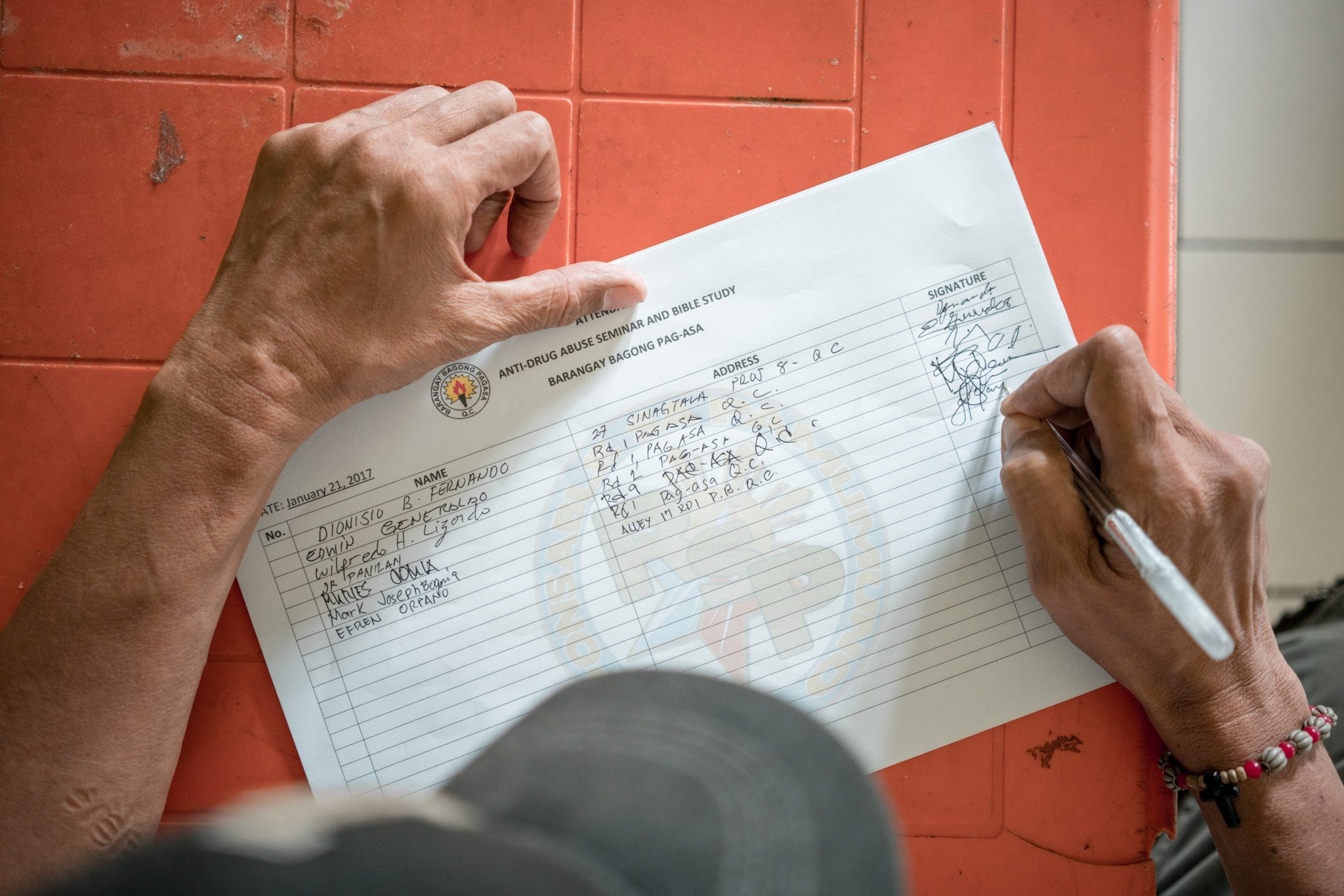

Those who attend Renato’s sessions are given proof of attendance which they can present to authorities who are involved in Oplan TokHang, the Duterte government’s controversial anti-drug operation.

Seed of hope

There were very few attendees during the first few weeks. At one point, there were only two participants. As weeks went on, many more came. On the third Saturday of January, 52 surrenderers attended.

Some attended out of fear but others went willingly as news spread that the barangay’s rehab wasn’t bad at all.

“May surrenderer nga ako dito, notorious ‘yun; nasa watchlist. Number 2 yata sa barangay – user, tapos ngayon, siya na ‘yung nagdadala ng mga kaibigan niya dito (I have a notorious surrendered here. Number 2 in the barangay. He now brings his friends here to the rehab),” Renato proudly shared.

Jun, 47, convinced 4 of his friends to surrender and participate in the weekly sessions.

“Sinabi ko lang sa kanila na maganda naman pala summurender….Kaysa naman mamaya puntahan kayo diyan, buksan ang pinto (at) barilin na lang. Mas maigi (kung) sumurrender na lang kayo (I just told them that it’s not bad to surrender…Instead of police going to your house, opening your door, and shooting at you. It’s better to just surrender),” Jun recalled telling his friends.

“Hindi na kami nagtotokhang; siya na kusa. Mga dependent din yung dala niya. Ang galing nga e. Doon ako natuwa! (We don’t have to do TokHang anymore; he does it voluntarily. He brings dependents here. It’s amazing. It makes me happy!)” Renato added.

Some surrenderers proudly shared that they had never been absent since joining the program. “Wala kami absent mula noong November 21 (We have never been absent since November 21)!” said Marilyn, 39, a former user of marijuana and shabu.

Jennylyn, 32, said she found the activities fun and informative. Despite not being tagged in the police drug list, she always accompanied her husband in attending the weekly sessions, where she volunteered to collect attendance sheets for Renato to sign.

Hurdles

Renato’s efforts remained unfunded since it started in September of 2016. Its allocation from the 2017 budget of the barangay was still under deliberation.

Like most barangay workers, Renato only receives a P5,500-monthly allowance for the work and dedication he puts in for the community. The rent for their house alone is P8,000, so he needs to do extra work as a part-time photographer to meet the needs of his wife and two kids.

Renato admitted the difficulty of handling the program on his own. He shared that the barangay had been trying to hire people but no one wanted to work for BADAC. Even his fellow barangay workers are hesitant to help in his intiative.

“Ayaw nilang humarap. Ayaw nilang makilala. Ayaw nilang ma-involve (They don’t want to face the surrenderers. They won’t want to know them. They don’t want to get involved),” said Renato.

Absentees have also added to his woes. “(Kapag) hinihingi na ng Station Anti-Illegal Drugs (SAID) pangalan ng hindi uma-attend, doon ako naiistress (I get stressed when SAID requests for the names of those who no longer attend session!!)”

“Wala akong maipakita. Baka sabihin pinagtatanggol ko kayo, kasabwat pa ako (I have nothing to show them. They might even say I’m protectingyou, that I’m an accomplice),” a frustrated Renato told a surrenderer who asked for a certification of attendance even though he attended only one session.

Asked if he received death threats, Renato smiled and said he would delete them right away to avoid negativity.

Despite these hurdles, he never lost the drive to keep his promise.

“Kung bibitawan ko ‘yan, para silang anak na iniwan ng nanay mo; baka magrebelde. ‘Yun ang inisip ko talaga e. Nakuha ko na tiwala nila. Tingnan mo, wala na tayong kasamang pulis. Basta ako, tinutuloy ko programa ko,” he said.

(If I leave the program, they’ll be like children abandoned by their mothers; they might rebel. That’s what I’ve been thinking. I already got their trust. Look, we don’t have police watching us anymore. I just want to continue my program).”

Renato makes rounds every weekday morning on his red motorbike to personally tell his surrenderers to attend the next Saturday session.

“Binibisita niya kami! Dinadaanan niya kami araw-araw! (He visits us! He passes by where we work everyday!” shared Jennylyn, a barker outside a mall in North EDSA.

As a parent, Renato said he was also doing this for the welfare of his children.

“Kaya ko ginusto to, kasi ‘yung anak ko inaya ng marijuana sa loob ng school. Nagsumbong ‘yung bata. Sa CR, hinarang siya. Nagpunta ako sa school, kinausap ko yung principal ayaw nila kumibo, ayaw nila makialam. (I wanted to do this because one of my sons was asked to take marijuana inside their school. I talked to the principal. They didn’t want to do anything, to get involved.”

Shortcomings in the government’s efforts

For Renato, there are aspects lacking in the government’s efforts to curb illegal substance use.

“Inuuna nila ‘yung nasa baba. Dapat uunahin ‘yung nasa taas. ‘Pag wala nang makuhanan ‘yang mga ‘yan, titigil yan (They’re prioritizing those at the bottom. They should address first those at the top. If those at the bottom can’t get anything anymore, they’ll stop).”

He added that the lack of rehabilitation facilities for the influx of surrenderers was also a problem.

A total of 1,176,523 have surrendered nationwide under Oplan Tokhang as of January 27, 2017.

The Department of the Interior and Local Government, however, said that only 1% or 11,765 needed to be turned over to rehabilitation centers, while the rest must be integrated into community-based programs like that of Barangay Bagong Pag-Asa. (READ: Robredo: Family, church key in nat’l drug rehab program)

On January 30, Philippine National Police (PNP) chief Director General Ronald Dela Rosa ordered all anti-illegal drug operations stopped nationwide. This came hours after President Rodrigo Duterte ordered the dissolution of all anti-illegal drug units in the PNP following the murder of a South Korean businessman inside Camp Crame itself, the national police headquarters, in October 2016. (READ: Dela Rosa orders PNP: Stop war on drugs)

“Inalis nga ang Oplan Tokhang, e ang Oplan Tumba (Oplan Tokhang was removed, but what about Oplan Tumba)?” he asked, alluding to extrajudicial killings.

Renato felt that Dela Rosa’s order would not yield positive results. Drugs users, he said, have become more afraid after the top cop’s announcement.

“Mas nakakatakot na nga ngayon e. Hindi na ako madadagdagan (ng surrenderers), didiretso na sa sementeryo (It’s even more scary now. Instead of surrenderers coming to me, they’ll head straight to their graves),” he lamented.

Hopeful

Despite such misgivings, Renato remained optimistic.

He believed that the community is the ideal space to rehabilitate the drug users. There is a safe way out without being a victim of the bloody war against drugs.

For him, the best approach is to treat them with respect, and encourage them there is life after being tagged as a drug addict.

“Sa akin kasi, gusto ko program. Kasi nakita ko ‘yung mga surrenderer, nakikinig sa akin. Kung iiwan ko, kung pababayaan ko…wala, baka lumiko. Magtatampo ‘yan pag iniwan ko, kasi ako ‘yung nag-alaga sa kanila,” he explained.

(For me, I’m in favor of the program. Because I can see that the surrenderers listen to me. If I leave them, if I forsake them, they might return to drugs. They’ll hold it against me if I leave them because I was the one who took care of them.}

“Ako’y nangangako na walang mamamatay sa inyo basta’t magbago lang kayo (I promise not one of you will die, just make sure you’ll change).” – Rappler.com

**Attendees mentioned requested surnames to be omitted for their security.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.