SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Many academics studying prison reform believe that imprisoned extremists spread their doctrines to other prisoners once they are kept in a shared facility over the years.

This has led to many countries preferring to isolate extremists and terrorists from other inmates to limit their exposure to potential recruits.

The findings of two experts, however, are challenging that idea.

From 2008 to 2018, Australian researcher Clarke Jones and and Filipino academic Raymund Narag visited Philippine detention facilities and spoke to over 100 inmates who had either been accused or convicted of being members of terrorist groups like the Abu Sayyaf and Jemaah Islamiyah.

“The complexities of dealing with this is far more complex than more experts believe,” Jones said on March 6 after he and Narag launched their book Inmate Radicalisation and Recruitment in Prisons at the University of the Philippines in Quezon City.

The two were made for studying the complexities of Philippine prisons: Jones is an expert criminologist with a focus on terrorist inmate management, and Narag is a former prisoner himself who has since become an academic studying prison reform.

Trapped thoughts in prison

The Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP), which manages detention facilities for those still on trial, put high-risk inmates in the Special Intensive Care Areas (SICAs), its facilities in Muntinlupa.

Jones and Narag found that putting violent extremists in seclusion only caused their beliefs to intensify.

“Since they are together, they are constantly exposed to each other’s thinking, then they could also harden into their understanding, into their previous causes,” Narag said in a mix of English and Filipino.

It was as if they were placed in an echo chamber, barring them from learning other ideas, leaving them unchanged throughout their years-long stay.

“If you isolate them, you put all Abu Sayyaf and JI [together], they harden. It’s an echo chamber. And there’s no avenue or opportunity for change because the social system doesn’t change,” Jones explained.

The social structure in the New Bilibid Prison allows inmates to adapt better.

Together is better

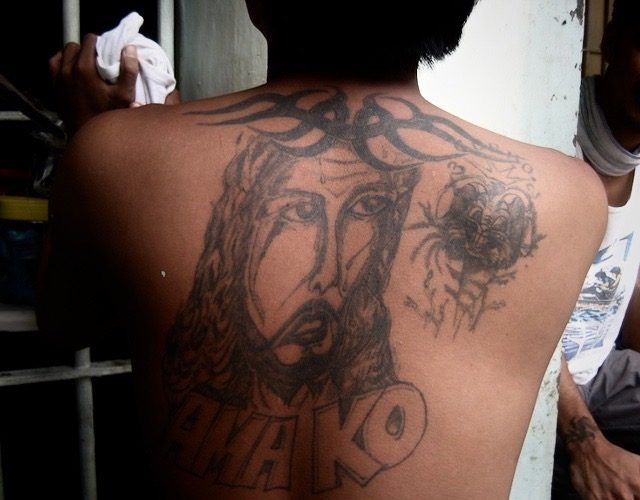

Managed by the Bureau of Corrections, the New Bilibid Prison houses convicts who committed heavy crimes. Inside, men with life sentences are not hard to find – they walk the same area, share the same meal, and sleep in the same cells as everybody else.

Those convicted for committing violent extremism stay in the maximum security compound, where they meet convicts who have committed other crimes, and carry other ideologies that could pull them out of their extremist ideals. (IN NUMBERS: The inmates of New Bilibid Prison)

This setup, according to Jones and Narag, is beneficial for extremists who still have the potential for change. And they have seen that most of them do.

“There are benefits to integration and one of that is they become part of the community, they become active in the day-to-day dynamics. They assume roles, they assume identities that may wean them off their engagement with violent activities,” Narag said.

These roles could mean taking part in the decades-old gang system, an informal arrangement by which inmates manage themselves, given that most correctional institutions in the Philippines are overcrowded but with barely enough prison guards.

“What we learned in the Philippine system is that radicalization, or the threat of radicalization, is quickly overruled, overrun by gang dynamics. So,there are factors that mitigate the risk,” Jones said.

These factors that lead prisoners away from extremist ideologies, Jones and Narag found, include relationships with fellow prisoners, the hobbies they are pursuing inside, contact with their families, and religion.

Breaking away from old solutions

“You have to understand who’s in the zoo,” said Jones.

They recommended that detaining and correctional institutions should categorize inmates with violent extremist tendencies based on the risks they pose. With this, jail officers could decide how to minimize risk and maximize rehabilitation. Does a prisoner need more religious programs? Should a prisoner be allowed to see his or her family more frequently? Is a prisoner too risky to be allowed to socialize with others?

“We’re not denying that there are bad offenders. We’re not denying that isolation is necessary for some offenders,” Jones said.

The two then pitched the idea of the government working with the prison gangs instead of aiming to abolish them. It’s already an organic arrangement and would almost be “impossible” to dismantle, they said.

With a so-called “shared governance framework” inmates could be allowed and even given incentives to assume leadership roles, as long as they do it under the watch of prison administrators.

“It’s like inmate councils that, you know, are part of your governance arms in the prisons,” Narag said.

Narag and Jones acknowledged that their findings do not solve everything about the Philippines’ jail problem. Something has to be done first about the facilities that are bursting in the seams, and inmates have to be provided with abundant rehabilitation opportunities during detention.

In other words, the Philippines has to turn its jails into jails that work. – Rappler.com

Clarke Jones and Raymund Narag detail their experience and findings in their new book Inmate Radicalisation and Recruitment in Prisons. Grab a copy here.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.