SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Rappler first published this touching piece in March 2012. In honor of mothers — both willing and unwilling, both prepared and ill-prepared — we are republishing it today. Women will agree that motherhood is both a painful and joyful experience.

MANILA, Philippines – The scene is always touching—mothers, sometimes up to 6 of them, lying side by side on beds arranged in tandem, lovingly and protectively nursing their newborns.

Truth is, a few of them are making the heart-rending decision to give up their tiny ones.

We are at the service wards of the Dr Jose Fabella Memorial Hospital in Sta Cruz, Manila. In this maternity hospital run by the health department, an average of 50 babies are born every day.

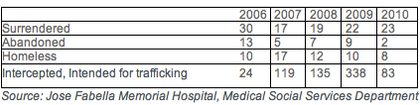

Out of those 1,500 infants each month, 9 could end up being surrendered for adoption, abandoned, or rescued from trafficking. Not so long ago, as of 2009, as many as 30 every month were given up by their mothers.

The reason, almost all the time, is poverty. The poor, after all, make up most of Fabella’s clientele—95% of total admissions are service patients (“service” being the politically correct term for “charity” in government hospitals); out of the hospital’s 700 beds, only 15 are for fully paying patients.

In the service wards, normal delivery, including doctors’ professional fees, costs only P2,000; cesarean delivery, P6,000. Even at these deeply discounted rates, more than a third of the patients can only pay a quarter of the cost, and another third don’t have the capacity to pay anything at all.

“Marami sa kanila, walk-in [patients],” said Rowena Aggabao, who heads the hospital’s medical social work services department. They haven’t had previous checkups with Fabella’s resident or consultant doctors and just rush to the emergency rooms when they’re about to give birth.

As soon as patients express their preference to be admitted to the service wards, an indication of a limited or lack of capacity to pay, they are interviewed by Fabella’s social workers.

In those deftly handled conversations, red flags are immediately spotted.

Interviews

How old is she? Is the one accompanying her her husband or partner? What do they do for a living? She could be an unwed mother not prepared to have a child.

Is she from a distant province? Is her address in Metro Manila or the surrounding provinces authentic? Is she known to the barangay chair or residents? She could be a homeless woman who cannot keep a child.

Is the one bringing her to the hospital or expected to fetch her not a relative? Does she mention some other person offering to cover even her discounted hospitalization expenses? She could be wittingly or unwittingly engaging in the trafficking of children.

These women are immediately subject to close monitoring and follow-up interviews by the social workers. Further verification of stated places of residence are made, the Department of Social Welfare and Development is alerted, and counseling is administered.

Poverty

Contrary to common perception—that maybe minors, unwed mothers, or abandoned women are unprepared for the responsibilities of child-rearing—the babies being contemplated for adoption are not firstborns. Fabella records attest that, many times, they are babies from succeeding pregnancies, suggesting that it’s poverty that’s driving the mothers to do it.

Such was the case of Jocelyn (not her real name), a 33-year-old laundrywoman from Bacoor, Cavite, who told the social workers right off in June 2011 that she wanted to put up her baby for adoption.

“Di ko na po kayang buhayin ang anak ko,” Jocelyn was quoted in her case file. (I can’t support my child.)

She gave birth to a baby girl, her third child by a third partner who had abandoned her. She was the second child she was giving away. She had given up her firstborn for adoption in the Visayas, where she hails from. She said that after giving up her third child, she intended to have a fresh start with just her second child, a son.

It’s worth noting, however, that Jocelyn’s case was the only one in the “surrendered child” category that Fabella has for 2011. It’s one huge drop from the numbers for previous years. In 2010, there were 23 babies surrendered for adoption. In each of the 4 years before that, the numbers ranged from 17 to 30.

The number of abandoned babies, however, had seen its peak in 2006—with 13 left by their mothers, who “just removed their patients’ tags, changed from their hospital gowns, and casually walked out like they were just visitors,” Aggabao said. The number has since dropped to two in 2010.

Trafficked

The biggest, and alarming, numbers are those of babies “intercepted for trafficking,” which used to run by the hundreds. From only 24 cases in 2006, it shot up to 338 in 2009.

The sharp increase in the number of recorded cases of trafficking in children was due to the tight watch that Fabella’s management started to carry out. The figures have since dropped to 83 in 2010. No case was recorded in 2011.

To be clear, trafficking here is not necessarily one involving women being used by syndicates or a third party to get pregnant and sell their children. It can be one of a mother committing the pre-meditated act of selling her baby to a waiting person or couple.

That’s easy to catch, Aggabao says. “When filling up the birth certificate, the mother wants to put the adoptive parents’ names in the form, instead of her and her partner’s names. It means there’s been a prior arrangement, nagbayaran (there was an exchange of cash).”

Babies who are surrendered or abandoned by their mothers, or those taken by the DSWD are referred to any of the 10 orphanages and nongovernmental organizations that Fabella has been working with, all accredited by the department.

This is not always easy, though, because each organization or halfway house can only take care of a limited number of babies over certain periods of time. At times, Fabella takes care of those babies over a period of time. Jocelyn’s baby, for instance, didn’t get adopted until she was 6 months old.

“Hindi palaging may bakanteng crib,” Aggabao said. (There isn’t always an empty crib.)

Available help

Serious counseling with mothers (Fabella recently expanded its complement of social workers) has largely contributed to the almost elimination of cases of mothers giving up their babies.

Clearly, when they overcome their fears and anxieties about giving their babies a decent life, when they are made to understand that there’s help available for both mothers and children from facilities within and outside government, mothers instinctively hold on to their babies once more.

“Madalas kasi, wala naman silang balak na ipaampon talaga ang bata—minsan, kasi nagkagalit lang ang mag-asawa, o natatakot kasi marami nang anak, o hindi raw handa,” Aggabao said. (Often, they don’t really have plans to have their babies adopted—sometimes it’s because the couple fought or got scared by the prospect of having many children, or is unprepared.)

Such is the case among mothers who are found to be homeless in mega-Manila. After receiving counsel and time to reflect, they rule out giving up their babies for adoption and instead agree to be committed—with their babies—to housing institutions until the mothers are ready for their responsibilities.

“We’re doing this because we don’t want Fabella to be labeled as a place where putting up babies for adoption is easy, or common. But it’s more than that,” said Aggabao.

We have to walk by those rows and rows of beds in the expansive service wards to know what she’s talking about. Here, mothers of babies born prematurely are holding their tiny ones against their breasts, skin-to-skin, for hours each day. As a kangaroo mom would do for its joey, the mother’s body temperature becomes the baby’s incubator.

Here, even moms who are tied to intravenous sets ignore their own physical pains just to pull their babies closer and caress them.

“Ipinapaliwanag namin sa kanila,” the head social worker said, “Hindi lahat ay nabibiyayaan ng anak.” (We explain to them, not everybody is blessed with a child.) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.