SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – On February 25, 1986, Sister Helen Graham rushed to Club Filipino to watch the inauguration of Corazon Aquino as Philippine president. The mass of people on Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue, more commonly known as EDSA, had not dissipated.

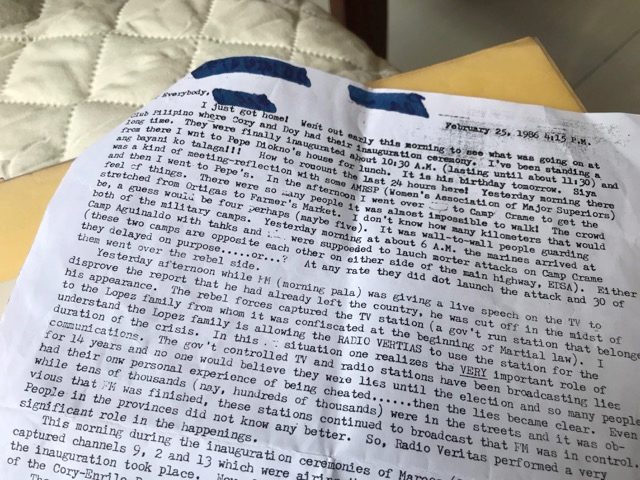

“There were so many people it was impossible to walk! The crowd stretched from Ortigas to Farmer’s Market…It was wall-to-wall people guarding both of the military camps,” she gushed in a letter she wrote at 4 in the afternoon.

Though Aquino, wife of the murdered opposition figure Ninoy Aquino, was being sworn in with the jubilant support of those on EDSA, victory was far from a done deal.

President Ferdinand Marcos, in power for two decades at that point, was also proclaiming victory. At 12 noon, he was set to hold his own inauguration. But anti-Marcos forces took control of television channels previously held by the government, wrote Sister Helen. They cut off the broadcasts before his inauguration could take place.

Until then, Marcos dictated broadcast communications in the country. His cronies had long taken over media companies, including the television and radio stations owned by the Lopez family – what we know today as ABS-CBN. The network now faces a shut-down under President Rodrigo Duterte, who has proclaimed his support and closeness to the Marcos family, decades after they were shown Malacañang’s door.

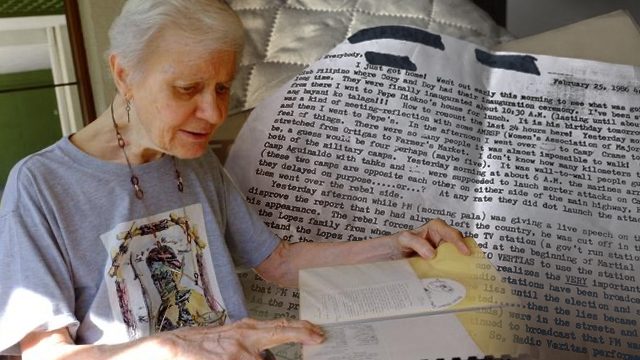

“In this situation, one realizes the VERY important role of communications,” wrote Sister Helen on that historic day in 1986. She shared her letters with me and agreed for them to be published on Rappler.

“The government-controlled TV and radio stations have been broadcasting lies for 14 years, and no one would believe they were lies until the election and so many people had their own personal experience of being cheated,” she continued.

Though rebel forces appeared to be winning, uncertainty reigned at that point. No one knew where Marcos was and what he would do. Rumors circulated that he would leave the country, if he had not already done so. The threat of violence erupting remained.

“The situation is grave at the moment and will be for the next few days. FM (Ferdinand Marcos) has called on all his goons to come and defend him. There are snipers everywhere. Hundreds of thousands of people are in the streets protecting the different TV stations from the loyalist forces,” Sister Helen reported. (READ: Key players in the 1986 People Power Revolution)

The Maryknoll nun, who had visited political detainees in camps and written reports on their torture by the military, was herself at the EDSA gathering.

From her spot on Bonny Serrano Avenue, she saw middle and upper-class Filipinos stream into EDSA, shaken from their silence by the brazen murder of Ninoy Aquino.

“I saw men with little babies on their shoulders. It was a fiesta kind of mood. People were not scared. And there was food which is was what Fiipinos like all the time,” she recalled in an interview with Rappler.

Activism then and now

When Sister Helen first set foot in the Philippines in 1967, she had no idea she would one day take part in a historic rally that would lead to the ouster of a dictator. Born in Brooklyn and raised by her grandparents, she had joined the Maryknoll order in 1956 and was first sent to teach high school in Cotabato. But years later, she was dispatched to Manila to teach theology in Maryknoll College.

The EDSA Revolution has been hailed as a victory of democracy and proof of what peaceful protests can accomplish.

Thirty-four years later, is the EDSA Revolution still relevant?

I asked her what physical activism – showing up at rallies, boycotts, or wearing something in protest or in support of something – means in a Philippines where digital activism is commonplace.

Today, many movements take place online – whether its making a hashtag trend on Twitter or masses of Facebook users using a profile photo frame to oppose something or support a group.

For Sister Helen, nothing beats physical activism in terms of impact.

“I think unless you get a mass of people out on the streets, nothing will change. Not to pick up guns but to get out in the street peacefully, overwhelm them with the number. Because it’s visible,” she said.

She cited the Hong Kong protests, which, though they manifested online as well, had a physical component. Students gathered in airports and on the streets, disrupting daily life and bringing international attention to their demands.

To Sister Helen, those physical protests and show of force likely made the Chinese government think twice about any overly violent or aggressive action “because the world was looking.”

Nothing gets the world to look more than an astonishing number of people coming together for a common cause.

Sister Helen was in her 30s when she started visiting political detainees in military camps during Marcos’ martial law regime. Her activism started when her former theology student was thrown into prison herself after watching soldiers murder her husband.

She would help political prisoners in other ways, from helping smuggle their letters out of jail to writing comprehensive reports about their accounts of torture so others, particularly foreign groups and governments, would know what was going on.

Those were heady days. Sister Helen, now 82, recalls them as an explorer remembers their exploits – with excitement, and a little sadness.

Forgetting

In an old house of the Maryknoll sisters in Quezon City, surrounded by trees and ferns, Sister Helen tells me she thinks Filipinos still have much to learn from the EDSA Revolution.

She says she’s “heartbroken” by the Duterte presidency.

“Practically, martial law exists here. It doesn’t have that name but I think it’s getting worse,” she says, citing the attempts by the government to shut down ABS-CBN.

“We learned nothing,” she adds.

It takes time to get people’s movements going and no movement is perfect. Sister Helen has her own criticisms of the EDSA Revolution.

For her, it was not really a “people’s revolution” but a revolution of the middle class. It took the murder of a prominent senator from a privileged family to get the middle class and upperclass out into the streets even when many other murders, tortures, and other grave injustices had been perpetuated before then. (READ: [OPINION] The most common misconceptions about EDSA People Power)

Juan Ponce Enrile and Fidel Ramos, then the military and police chiefs, respectively, were hailed as heroes and appointed to Cory Aquino’s government despite their role in the Marcos dictatorship.

“These are the same ones who have run the military during the martial law period. They are responsible for thousands of arrests, torture, murder, disappearances, etc,” Sister Helen wrote in her February 1986 letter.

More than anything, the EDSA Revolution has taught us how quickly Filipinos as a nation can forget.

Sister Helen bemoans the return of the Marcoses to power. The same family booted out of Malacañang for plundering the nation’s coffers and making a mockery of its democratic institutions won new government posts in the 2019 elections.

Filipinos overwhelmingly elected Rodrigo Duterte, a man who promised to give Ferdinand Marcos a hero’s burial and would have his namesake back in Malacañang.

Yet again, media groups are being threatened into silence and critical voices make do with shrinking spaces to express dissent. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.