SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

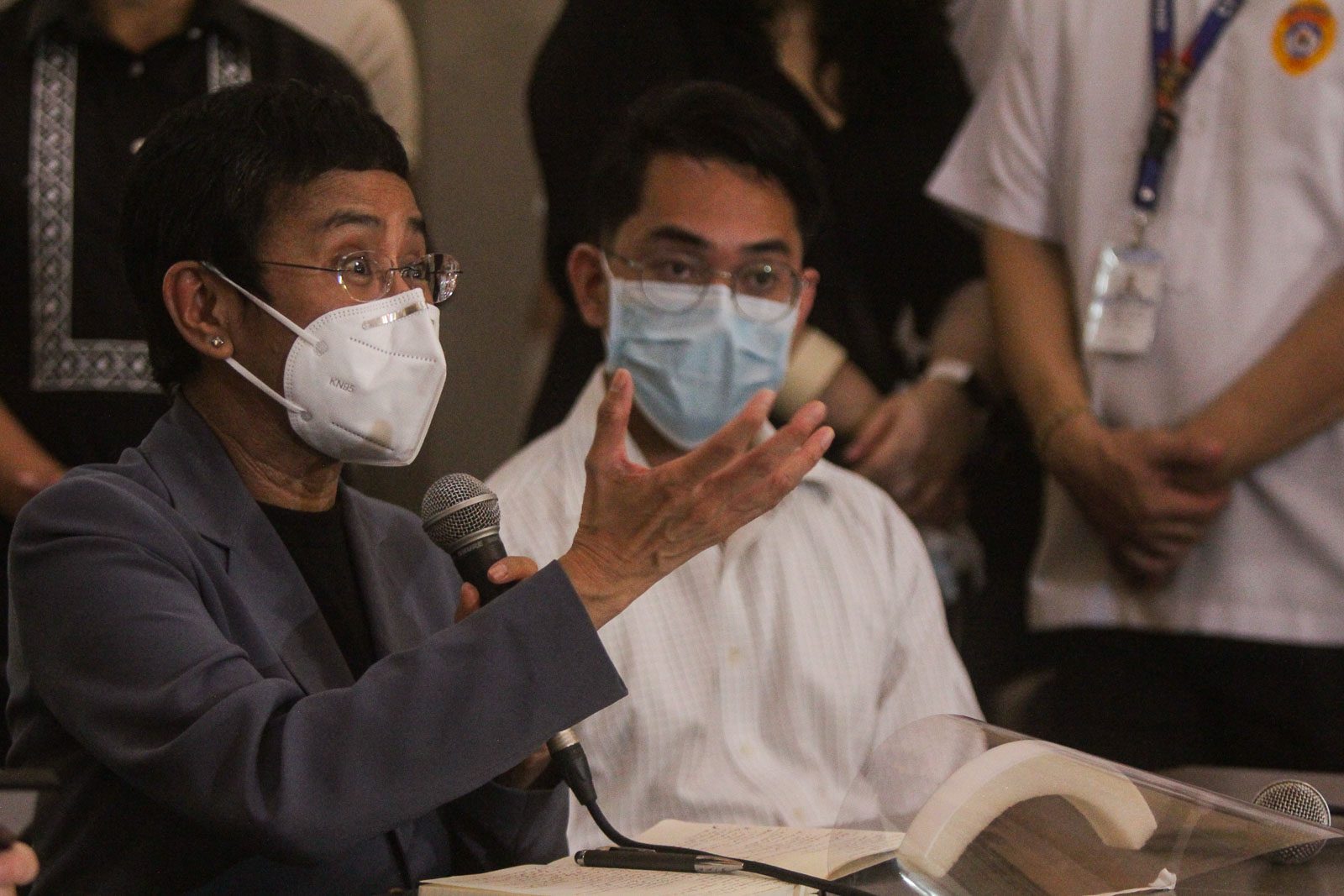

MANILA, Philippines – Manila Regional Trial Court Branch 46 Judge Rainelda Estacio-Montesa on Monday, June 15, convicted Rappler CEO and executive editor Maria Ressa and former researcher-writer Reynaldo Santos Jr of cyber libel, in the most high-profile case filed against individual journalists during the Duterte administration.

On Monday, the anti-disinformation network Consortium on Democracy and Disinformation slammed the ruling as “unjust, uncomprehending, and unconstitutional.”

We are publishing in full the Consortium on Democracy and Disinformation’s statement.

***

The Consortium on Democracy and Disinformation condemns the unjust, uncomprehending, unconstitutional decision in the cyber libel case against Maria Ressa, Reynaldo Santos Jr, and Rappler. Presiding Judge Rainelda Estacio Montesa of the Manila Regional Trial Court Branch 46 has failed the Constitution, the rule of law, and the country’s long and proud tradition of defending the freedom of the press.

The decision was UNCOMPREHENDING, because the language of the decision proved that the court failed to understand how journalism works and what its role in a democratic setting is. Of the many micro-aggressions against the institution of the free press visible in the ruling, let this example suffice. “To the mind of the Court, Rappler’s scheme of not using the term ‘editor-in-chief’ in its organizational structure is a clever ruse to avoid liability of the officers of the news organization.… They used the nomenclature ‘executive editor’ instead.”

This is just unfortunate, and we wish Judge Estacio Montesa, who must have been aware that she was in charge of a case that had drawn worldwide attention, could have reminded herself to use Google. The top editors of the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Philippine Daily Inquirer, and many other newspapers and news sites around the world are called “executive editor.” This “nomenclature” may be new to her, but it is not limited to Rappler and, it is, in fact so commonplace that to declare it “a clever ruse” to avoid liability shows Judge Estacio Montesa’s apparent unfamiliarity with the terrain that is journalism.

The decision was UNCONSTITUTIONAL. In her peroration, Judge Estacio Montesa sought to explain her decision as a striking of the balance: “The right to free speech and freedom of the press cannot and should not be used as a shield against accountability.” True enough, but in scouring through Philippine and even American jurisprudence, she found only those passages that emphasized the responsibilities of the press – not the fundamental importance of a free press in the functioning of a democratic society.

Deliberately or inadvertently, she sounded like she was arguing that the court was the gatekeeper of journalistic standards. But when free speech and freedom of the press are at issue, the bar for considering any restriction must be set very high – not because journalists are privileged persons, but because the freedoms at stake are used by everyone. Thus, in ruling against a news organization on flimsy grounds, and in extending the coverage of the Cybercrime Prevention Act backward in time without so much as a chastened sense of responsibility or reflection, Judge Estacio Montesa helped turn the rule of law into a weapon – and puts us, every single one of us who uses online and social media, in peril.

The decision was UNJUST, because the crux of the court’s reasoning was based on a falsehood. For the Cybercrime Prevention Act, which became law in September 2012, to apply to the Rappler story published four months before, in May 2012, the court had to resort to the legal doctrine of republication. The court said the “update” to the article made in February 2014 satisfied that doctrine. “The court considers the update a republication of the article.”

But Rappler testified that it was only a mere correction of a misspelling: “evasion” had been spelled “evation.” Judge Estacio Montesa sweeps this all away with an appalling display of ignorance: “the original article published on 29 May 2012 can no longer be found. Only the 19 February 2014 version presently exists and [is] accessible on the internet.” But this is false. In fact the original article can still be found, through resources such as the Internet Archive Wayback Machine, a long-standing repository of web pages. And sure enough, anyone – including Judge Estacio Montesa, who lectures on cybercrimes – can find the original article there, where the word “evation” can be easily seen.

Despite quoting the great Nelson Mandela, Judge Estacio Montesa through her decision has set us back on our own long walk to freedom. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.