SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – They are devices that are older than the 40-year-old rebel army that continues to use them. Various countries have banned their use. But communist guerrillas insist that landmines are a poor man’s weapon.

Five soldiers were injured in a landmine explosion attributed to communist rebels in Zamboanga del Sur last June 26. In just a span of two months this year, landmine blasts have killed 15 government troops and wounded 10 civilians.

The New People’s Army (NPA) continues to use command-detonated landmines in its guerrilla attacks against the police and the military. Landmines were widely used during World War II, and in succeeeding conflicts including the Vietnam War, Korean War, and the first Gulf War.

According to the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), almost all armed forces in the world deployed the weapons until the 1990s. The Nobel Peace Prize-winning campaign helped bring about the 1997 Ottawa Treaty or the Mine Ban Treaty, which significantly reduced landmine use across the world.

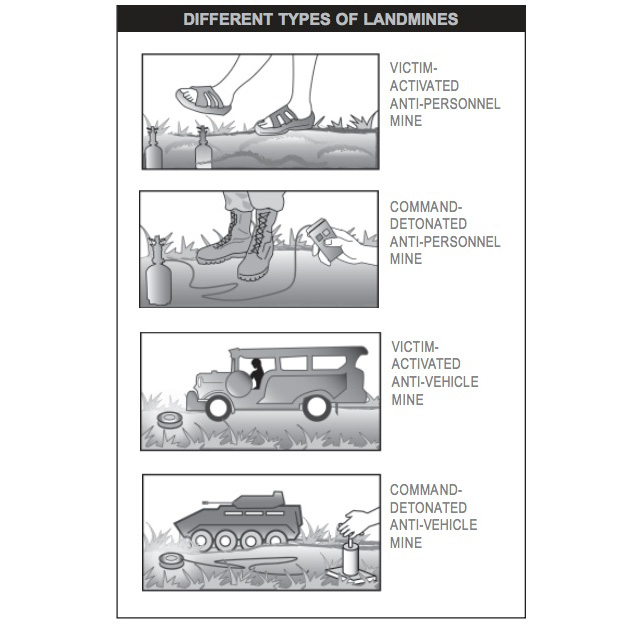

The treaty defines landmines as “a munition designed to be placed under, on or near the ground or other surface area and to be exploded by the presence, proximity or contact of a person or a vehicle,” specifically banning victim-activated anti-personnel mines (APM). Landmines can be categorized as either an APM or an anti-vehicle mine (AVM). They can either be command-detonated or triggered by a victim who steps on it.

Countries such as China, Cuba, India, Iran, Myanmar, North Korea, South Korea, Pakistan, Russia, Singapore, the United States, and Vietnam did not sign the treaty and reportedly continue to produce the munition.

The Philippines ratified the treaty in February 2000, maintaining that it never produced and exported anti-personnel mines. The Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) claims it does not use these weapons against insurgents.

Sison: Weapon of the poor

But the NPA, the military arm of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), does.

Between May and June this year, rebel-instigated landmines killed 15 cops and soldiers and wounded 11 troops.

Jose Maria Sison, the founding chairman of the CPP, said that landmines are necessary to deter security forces from encroaching on the “territory of the people’s democratic government” while the armed conflict is ongoing.

“Landmines are a poor man’s weapon. Aerial bombing and artillery fire are weapons of those who oppress the people,” Sison told Rappler in an online chat. Sison lives in Utrecht.

The Aquino government has criticized the NPA’s continued use of this device, saying it violates laws on landmines and international humanitarian laws.

The National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP), which represents the CPP and the NPA in the suspended peace negotiations with government, belies the accusation. “The use of command-detonated landmines by the NPA does not violate the Ottawa Treaty and its protocol. In this regard, the NDFP is well advised by an international legal advisory team composed of prominent lawyers who are experts in international law,” Sison, currently NDFP’s chief political consultant, told Rappler.

Landmine Incidents Attributed to NPA

The Philippine Campaign to Ban Landmines (PCBL), an affiliate of the ICBL, said that local landmine incidents attributed to the NPA involve improvised command-detonated AVMs.

In the case of the Cagayan Valley ambush in May 27, which killed 8 members of the elite Special Action Force of the Philippine National Police, the PCBL observed: “The 30-member unit of the NPA’s Danilo Ben Command in western Cagayan detonated an improvised command-detonated anti-vehicle mine (AVM)…with the landmine blast being followed by automatic rifle fire from an elevated portion of the road side.”

“This scenario has been an NPA ambush tactic trademark for a good number of years already,” according to Camarines Judge Soliman Santos Jr, PCBL founding coordinator.

Legal but not moral

Santos explained that command-detonated landmines, which are not banned under the Ottawa Treaty, can be regulated as “legitmate weapons of war.” They require the presence of a person to observe the landmine position and detonate it to hit only legitimate targets.

“If war cannot be avoided because of, say, the failure of a peace process, then the next best thing is to ‘humanize’ it or mitigate its adverse effects on the civilian population,” Santos said.

“In the current situation of terminated peace talks and intensified armed conflict, as we said, it may be legally (under IHL) and militarily correct for the NPA to continue to use its command-detonated landmines but it should also study well the impact of all these explosions on its political capital and moral ascendancy,” Santos said.

But from a human rights perspective, the technical and legal debate on landmines is irrelevant, the Human RIghts Watch (HRW) stressed.

“The most relevant and important issue is that any side in a conflict, whether it’s a government official, military or an insurgent group, both sides have have an obligation to protect civilians from threat and from harm. Any situation in which an armed group – whether it’s an army or an insurgent group like the NPA has targeted or victimized, intentionally or not, civilians – this is a human rights issue,” HRW’s deputy director for Asia Phelim Kine told Rappler.

APMs indiscriminately hit combatants and civilians, and the weapons have already claimed at least half a million lives around the world to date.

Campaigners against landmines pointed out that the munitions are not only deadly, they also deprive rural communities of livelihood as lands become unsafe for agricultural activities, settlement, and transit during or after an armed conflict.

The ICBL believes that the weapons still pose “a significant and lasting threat” to civilian populations. “Peace agreements may be signed, and hostilities may cease, but landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERW) are an enduring legacy of conflict,” the ICBL stated in its 2012 report.

Counterproductive

The NDFP argued that landmines are not the biggest source of destruction and harm against civilians.

“To ban landmines, per se, to be judgmental about it on the basis of violations, gives a distorted picture of how the war is being conducted. The Armed Forces of the Philippines uses bigger bombs – more powerful, more indiscriminate, more frequently used – bombs and artillery which AFP routinely uses if they have operations,” NDFP consultant Rey Claro Casambre said.

The NDFP said it recognized international humanitarian laws even before the ratification of the Ottawa Treaty.

In 1996, the NDFP released the Declaration of Undertaking to Apply the Geneva Conventions and Protocol 1 and submitted it to the Swiss Federal Council. This signified the adherence of the revolutionary forces to the guidelines for armed conflict, which include the protection of civilians and military forces who are no longer in a position to fight, according to NDFP consultant Rey Claro Casambre.

Casambre also noted how the NPA abandoned the use of lethal traps in its conduct of guerilla warfare. “Early on, na-realize na counterproductive siya. Pwedeng masa mismo, kahit mga kalabaw napipinsala dahil dyan,” Casambre told Rappler. (Early on, we realized that it was counterproductive. It harms the masses, even their carabaos.)

File a complaint

The NDFP said that the revolutionary forces are open to criticism and complaints. “My message to any real or possible complainant against the NPA is to present the complaint to the NDFP section of the Joint Monitoring Committee under the Comprehensive Agreement of Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law (CARHRIHL) or to approach directly the people’s democratic government, particularly the people’s prosecutors and the people’s courts,” Sison said.

CARHRIHL, a special agreement signed between the government and NDFP in 1998, guarantees “the right not to be subjected to forced evacuations, food and other forms of economic blockades and indiscriminate bombings, shellings, strafing, gunfire and the use of landmines.”

It took 25 years for the government and the CPP-NPA-NDFP to agree on the CARHRIHL, the first of the 4 agreements in the “substantive agenda” of the peace process. Under this track, however, the negotiations have not significantly moved on.

The NDFP sticks to its 2005 proposal to have “an agreement of truce and alliance on the basis of a general declaration of common intent to realize full independence, democracy, and economic development through national industrialization and land reform.”

According to Sison, the agreement can be signed even as the peace talks continue to tackle the remaining 3 items in the substantive agenda.

“If there is such an agreement, the armed conflict ceases and there is no more need for land mines, aerial bombs and artillery fire or any other kind of weapon,” Sison explained. “The Aquino regime has only itself to blame if it offers no other possibility than the continuance and intensification of the civil war. It should see that the way is still available for peace negotiations,” Sison added.

But the government has already abandoned the old process which the communists continue to uphold.

“After assessing the behavior or the process itself, I was convinced that it was a process that would never end. That it was a process actually intended not for peace but to continue the war [and for them] to get concessions in the meantime,” resigned government peace panel head Alexander Padilla earlier said.

READ: ‘Joma wants peace, the ground doesn’t’

In a statement, Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process Teresita Quintos Deles said that “the government is currently developing a ‘new approach’ for the negotiations as a sign of its continuing commitment to deliver a peaceful resolution of the armed conflict in the country after it has yet again reached an impasse.”

Concerned about the deadlock, civil society groups called on the negotiating parties to rebuild goodwill and push forward with the talks.

“Instead of an eye for an eye, how about a moratorium on the use of one kind of explosive device in exchange for a moratorium on the use of another kind of explosive device? We dare both sides to accept this challenge on a relatively ‘small matter’ of weapons use – since they cannot seem to accept the bigger challenges of serious substantive peace talks,” PCBL’s Santos said.

For the HRW, however, what is urgent is for both sides to stop the violence. “A failure to do so only guarantees that there will be more civilian casualties, more civilian victims of a conflict which has already gone on for far too long,” Kine said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.