SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – When American actor Robin Williams took his own life, his death sent shockwaves all over the world, prompting an outpouring of grief and tributes to the life and career of the well-loved comedian.

One of the most viral tributes came from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, but what was perhaps intended as a poignant move became controversial after the Huffington Post reported that it seemed to be glamorizing the act of suicide.

The move reignited long-running questions on the ethics of reporting about suicide. Research has shown that extensive and sensationalized media coverage on suicide could spur imitative or copycat behavior among vulnerable individuals, particularly those suffering from mental health problems.

Experts from the Philippine Psychiatric Association (PPA) emphasized the need for responsible reporting in a forum on suicides and the role of media held on Tuesday, August 26.

Noting the worrying rise of suicide cases among Filipino youth over the last 3 decades, the PPA said local media should revisit its own guidelines and move towards educating the public on suicide prevention.

Filipino youth vulnerable

Globally, an estimated 1.2 million people die by suicide each year, roughly translating to one death every 40 seconds. Of these, nearly 60% of suicide deaths are among young adults in their productive years.

This means that suicide accounts for a lot of economic loss, as countries lose young people who could have contributed to society, according to psychiatrist Dinah Nadera.

In the Philippines, the lack of systematic reporting of suicide cases makes it difficult to observe general patterns of suicidal behavior.

But Nadera noted that over the past 3 decades, Filipino youth appear to be most vulnerable to suicide attempts.

Data from the National Statistics Office spanning 1975 to 2005 show that the highest peak in suicide rate occurred between the ages of 15 to 24 years old.

Between 1984 to 2005, the suicide rate among males jumped from 0.46 to 7 out of every 200,000 men. Among females, the rate went up from 0.24 to two for every 200,000 women.

A 2011 global survey conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) among public high school students also showed that 16.3% of Filipino adolescents have seriously considered suicide.

The proportion of those who actually attempted suicide is not far, at 12.9%. A small proportion – 3% – also said they had no close friends.

“This implies poor support system for this specific population,” Nadera said.

Irresponsible reporting

For every suicide death, nearly 10 to 20 people have attempted to take their own lives.

This is even more problematic in the aftermath of heavily publicized celebrity suicides.

Psychiatrist Dr Annie Cruz said excessive media coverage may tend to glamorize suicide and can lead to imitative suicidal behavior.

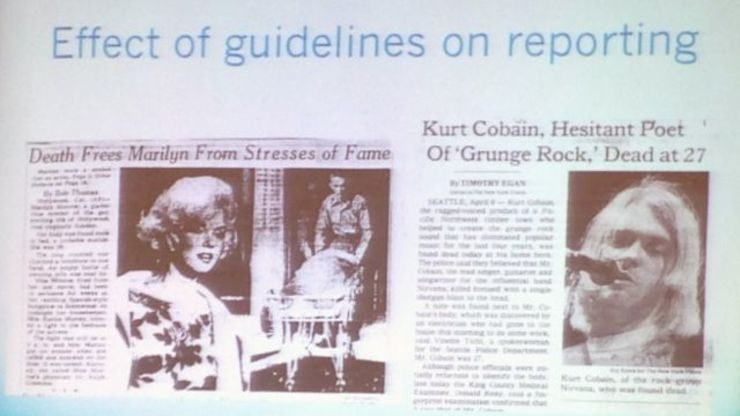

She contrasted the effects of media coverage on the deaths of American actress Marilyn Monroe and singer Kurt Cobain.

In one news article, Monroe’s death was described as “freedom from the stresses of fame.” The headline for Cobain’s death, on the other hand, was more straightforward.

The different approaches also yielded different results when it comes to the effect on spurring copycat behavior: following Monroe’s widely publicized death, there was a 12% increase in suicides – a jump from the average increase of 2.51% recorded when a suicide is reported.

In contrast, Cruz said reports following Cobain’s death highlighted the negative impact of his suicide, with articles focusing on how his death was a waste of talent.

Nadera also noted that Philippine media has its own share of errors in suicide reporting.

She recalled local media reports last year on the death of a young university student. Earlier reports said she took her own life because of her family’s failure to pay school fees.

The incident sparked controversy, with some sectors subsequently making the student the face of the flaws of the national education system.

Several years earlier, local media also reported on the death of a 12-year-old girl from Davao City, attributing her suicide to poverty.

Nadera said zeroing in on a single factor fails to take into account the complexity of suicide.

“Attributing suicide death to one single factor as if you have a person to blame, you have an event to blame, you have an institution to blame…It is a situation that is so devastating, you cannot just blame someone for the event. It is caused by several factors,” Nadera said.

She also criticized the explicit details in reports on people who killed themselves in public places.

“Showing the site and showing the method is a no-no, writing about it in a very detailed manner, almost cinematically describing it, is a very serious offense in suicide reporting,” Nadera added.

Instead of reporting on the specific details, Nadera said it’s time to change tack: focus instead on mental health issues and how to seek help. (READ: Reporting on suicide)

Suicide prevention

Mental health problems have been identified as one of the many complex factors behind suicide. But open discussion of these issues remains taboo in some communities, making it difficult for vulnerable people to seek professional help.

Cruz said this is where media can step in to help educate the public.

“We want to make sure that psychiatric illness is depicted accurately. We don’t want to further increase stigma, we want to challenge stereotypes and myths,” she said.

But the psychiatrists acknowledged that the challenge is greater now in the age of social media. While most news organizations have adopted guidelines on reporting on suicide, misinformation and rumors can run free and unchecked online.

“It’s difficult to monitor, censor, and give guidelines for social media use,” Nadera said.

But she added that experts are also looking at social media to improve efforts on spreading the word on suicide prevention.

“If we have good stories about suicide survivors, we have to share that. That’s prevention. If you have articles on reasons why you should not die, that’s a good article. We would like to use social media to share successful stories on suicide survivors. We are looking towards media partners to focus on prevention,” she said.

As a public health concern, the psychiatrists also emphasized the need for everyone to be involved in suicide prevention.

Dr Ma. Bernadette Arcena said friends and family members should be on the lookout for common warning signs, such as behavioral changes and verbal cues, to help loved ones with suicidal tendencies.

Equally important is early intervention and expressing empathy for the person.

“Having ideas, a plan, and the means to commit suicide constitute a very serious and immediate danger,” Arcena said.

“But suicidal thoughts cannot be kept a secret. The key is to help the person stop feeling invisible,” she added. – Rappler.com

The Natasha Goulbourn Foundation has a depression and suicide prevention hotline to help those secretly suffering from depression. The numbers to call are 804-4673 and 0917-558-4673. Globe and TM subscribers may call the toll-free number 2919. More information is available on its website. It’s also on Twitter @NGFoundationPH and Facebook.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.