SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – A year since super typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan), how far has the Philippines come in preparing for storm surges?

The term, previously esoteric for most Filipinos, barreled into the country’s consciousness when Yolanda caused a storm surge as high as a two-story building. Thousands of deaths were attributed to the phenomenon. It’s no coincidence that the highest death tolls were from coastal areas.

The government says they have made head-way in better preparing the country for storm surges. (INFOGRAPHIC: Storm Surge 101)

Scientists from Project NOAH (Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards), a program under the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), says the government now has the right tools to prevent casualties from the next Haiyan-scale calamity.

Some of the projects in the works are a storm surge advisory system and a more detailed storm surge simulation model that will allow vulnerable localities to determine where exactly the surge will hit them hardest.

Right after Yolanda, the DOST set out to compile a list of the top 30 localities most vulnerable to a Yolanda-scale storm surge. The idea is to identify which areas deserve priority given their extraordinary level of exposure to the phenomenon.

“We made storm surge simulations using the strength of Typhoon Yolanda. Each circle represents maximum probable storm surge height that an area can sustain,” explained Project NOAH researcher John Phillip Lapidez during a storm surge mapping forum on Tuesday, November 4.

He gestured towards a map of the Philippines full of red, orange and yellow dots pertaining to various storm surge heights – red for 7.2 meters (24 feet), orange for 5.6 meters (18 feet), yellow for 4.8 meters (16 feet).

The study simulated tracks of all typhoons that passed through the Philippines from 1948 to 2013 but using the strength of Yolanda.

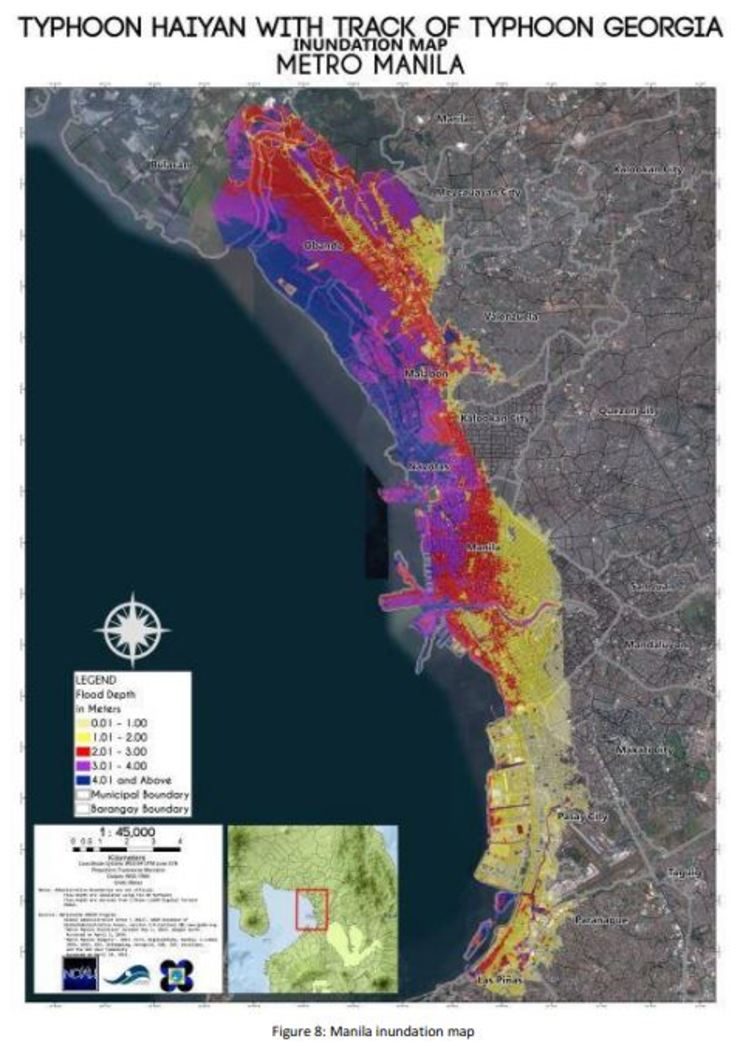

This allowed them to see which track would generate the highest storm surge for all parts of the Philippines. For instance, they found out that the highest storm surge for Manila would be generated by a Haiyan-scale typhoon traversing the track of Typhoon Georgia which hit the city in 1964.

Manila ranks 22 in the list.

The top 5 most storm surge-vulnerable localities are:

- Cabunga-An, Sta Rita in Samar

- Duka, Barugo in Leyte

- Alacalian, Taytay in Palawan

- Agdaliran, San Dionisio in Iloilo

- Esperanza, Cabucgayan in Biliran

Storm surge advisories

Project NOAH and state weather bureau PAGASA, also under the DOST, are working on a storm surge advisory system that will allow them to give storm surge warnings as early as 36 hours before the typhoon makes landfall.

Similar to PAGASA’s rainfall and gale warning advisories, the storm surge advisories will detail the various predicted heights of storm surge.

Storm Surge Advisory 1 to 4 will give alert on storm surge heights from 2 to 5 meters, said Lapidez.

“What we plan to do is prepare maps ahead for each of these advisories. When we have a forecast and when we can see that the typhoon can generate a storm surge of up to 3 meters, then we will give out the corresponding maps,” he said.

The localized maps should be able to show which parts of the affected area will be reached by the storm surge and what time the storm surge will reach its peak height.

The information should help local government units plan where to evacuate residents. This puts the country in a better position to lessen storm surge casualties.

“That’s what caused the tragedy in Tacloban. Some people knew that a big storm surge [was] coming but they didn’t know where to go because there weren’t very detailed maps available at that time,” reasoned Lapidez.

The DOST has finished mapping 50 out of the 67 coastal provinces for the planned storm surge advisories. The goal is to start rolling out the advisories in 2015.

Crucial to the storm surge advisories is the DOST’s project of developing a high-resolution storm surge simulator.

The project, Coastal Hazards and Storm Surge Assessment (CHASSAM), is supposed to provide a detailed simulation of forecasted storm surges.

At the time of Yolanda, the then two-month old project could only predict the height of an impending storm surge and the localities likely to be affected.

Once completed this December, CHASSAM will be able to provide a high-resolution simulation of how the storm surge will flood the localities. This will give LGUs, national government and residents an idea of what parts of their community will experience the highest floods.

In a previous interview, DOST Secretary Mario Montejo said CHASSAM is on track to meet the December deadline.

Science and tech not enough

But science and technology won’t be enough to avert disaster.

PAGASA scientist Esperanza Cayanan said during the forum that how LGUs make use of the available data makes a world of difference. (READ: ‘Storm surge’ not explained enough – PAGASA official)

But the capacity of LGUs to retain knowledge on disaster preparedness is limited.

“LGU officials have very short terms. One official may know all about hazard maps but he is replaced by someone who isn’t as knowledgeable. They need to be constantly trained,” she said.

Months after Yolanda, the DOST conducted a nation-wide information and education campaign to teach LGUs how to use DOST data on disaster preparedness.

The campaign, which toured all 17 regions, included workshops on how to understand multi-hazard maps, proper management of hazards and a tutorials on how to use the Project NOAH app and PAGASA website.

But campaigns like this can be costly if they have to be conducted every change of local government administration.

Some sectors have been suggesting a more long-term solution to the problem, said Project NOAH deputy director DD Tanjuakio.

“There were suggestions made, not by us, to make certain positions permanent or not necessarily tied to the term limits of LGU officials. Have another arm, maybe part of the national government, looking into the oversight function for the disaster arm of that LGU,” he said.

But he reiterated that it’s everyone’s business to make sure they are aware of the hazards their community faces in times of calamity.

In the end, what will make the difference is not how much data there is but how the data is used on the ground. – Rappler.com

For Rappler’s full coverage of the 1st anniversary of Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan), go to this page.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.