SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Gloria Arigo, 46, sews branded clothes for hours in a garments factory inside an economic zone south of Manila.

Despite working 11 years in the factory, she receives less than a new hire’s take-home pay.

Her case is not an isolated one.

Workers interviewed by Rappler who have served for more than a decade at the same Cavite-based garments factory said they are given a P1 addition on top of the mandated regional minimum wage to account for their seniority.

That one peso means they no longer qualify for a tax-free income exclusive to minimum wage earners.

They are taxed P780 a month, a deduction substantial enough that the actual amount they receive as pay is lower than the amount the minimum earners without income tax take home.

Likewise, any across-the-board addition to the minimum wage negotiated through the union means a net loss for workers due to taxes imposed.

In 2014, labor groups asked Aquino to exempt the floor wage of workers despite negotiated additions. This means that only the increase will be taxed.

Sitting in on dialogues with Aquino’s economic cluster Cabinet, Gerard Seno of the Associated Labor Unions said this move for exemption has since been granted by the President.

While there are gains, trade unionists continue to decry the lack of substantial improvement in the working conditions of many Filipino laborers.

They consider industrial work without the benefit of unions as poverty traps, with very little incentive for companies to provide due protection to the people who make the system profitable. (READ: Factory work and unionism)

Latest state figures show newly registered unions are at their lowest since 1976, with only 126 new unions registered in 2013.

This, despite a reported jobs growth in the country. (READ: More formal sector jobs boost growth – DOLE)

End contractualization

Widespread contractualization is also cited as a cause of dwindling labor union density.

Workers are hired in fixed terms for 5 to 6 months or are contracted out from a manpower company, short of being a regular employee.

Seno said any effort to unionize contracted workers is almost always curtailed when companies opt to end contracts instead of honoring regularization terms, which include providing health insurance, social security insurance, and other workers’ benefits.

On top of the calls of labor groups nationwide is for Aquino to certify as urgent a Security of Tenure Bill. (READ: No push from Aquino to pass pro-worker laws)

Varying versions of the bill have surfaced, including one that would limit contractual work to non-core and seasonal positions and only up to 20% of a company’s workforce.

A government version of the bill likewise intends to shift from a registration to a licensing system for manpower services, allowing only the agencies that deploy workers truly needed to be outsourced instead of directly hired.

From one factory to next

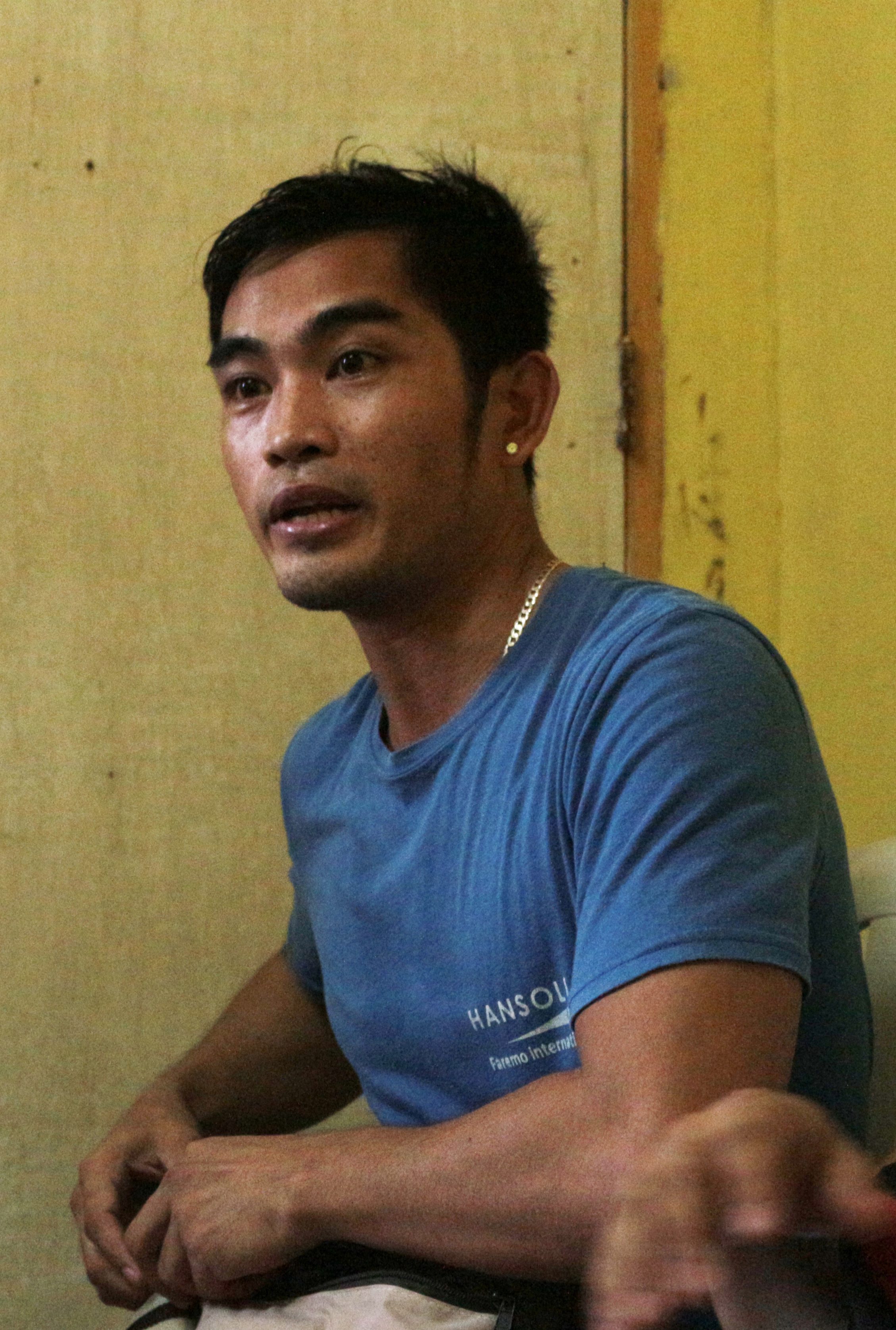

Reynaldo Perjes, 33, has spent 10 years jumping from one factory to the next.

He said most employers would only give him a position in the assembly line for 5 months, despite that position being necessary to the daily operations of the factory.

An International Labor Organization (ILO) study released last May 20 showed that one in 4 workers around the world are without stable employment.

In the Philippines, a government survey released in May 2014 show one in 3 workers in establishments with at least 20 employees are non-regulars. They represent 1.149 million of the 3.769 million establishment workers in the country.

Kentex and workplace safety

Like many contractual workers with no stable income, many of the workers of embattled local footwear maker Kentex Manufacturing were hired on a piece-rate system with no fixed wages. (READ: Deaths in PH factory show need for decent jobs)

The fire that gutted the two-story Kentex factory in Valenzuela, one of the worst industrial tragedies in terms of casualties, claimed at least 74 lives on May 13.

Four days before Aquino’s 6th and last State of the Nation Address (SONA), or two months after the deadly blaze, the justice department approved the filing of charges against select government officials including Valenzuela Mayor Rexlon Gatchalian and other private individuals.

Workplace safety became the battle cry of many of the fire victims’ relatives, with reignited calls to criminalize grave violations of occupational safety and health standards.

Dire working conditions were also found even in factories surrounding Kentex.

The deadly Kentex fire is viewed as a setback for the Philippine manufacturing industry, an industry like many in developing and booming economies that attract foreign investors partly due to cheap labor.

Power cost

Trade Union Congress of the Philippines (TUCP) executive director Louie Corral argues that the way to attract investors should be through lower utility costs especially power rates as well as upgraded skills of workers instead of lax labor standards and low pay.

Saying employers tend to cut down on labor when utility costs are high, Corral said government must regulate the generation of power in a way that would disable the artificial inflation of power rates.

He proposed the international public bidding of generation companies or power producers that power distribution companies enter supply agreements with.

Corral said power plant shutdowns should be physically inspected by a 3-party panel convened by President Aquino composed of representatives from government, civil society, and the power sector to prevent collusion attempts by power players. (READ: Tripartite inspection of power plant shutdowns sought)

Minimum wage

TUCP-Nagkaisa spokesperson Alan Tanjusay said an estimated 21 million “poor workers in the informal economy” earn an average monthly income of P6,408. They are the “construction workers, farmers, vendors, jeepney, bus, tricycle, pedicab drivers, conductors, salesladies, barbers, street-sweepers and garbage collectors,” TUCP explained.

Citing government poverty data, TUCP noted the P2,370 gap in their income to the poverty threshold or the amount they need “to move out of poverty.”

Saying the ideal minimum wage for now must be P1,068 a day, Seno urged “Aquino to make tough policy decisions in raising Filipino family income both at the formal and informal sector workers.”

“As a leader, he must ensure that the country’s growth is widely shared with the workforce who provided the backbone in building and sustaining the vibrant economy in the last 5 years of his administration,” he said.

In March 2014, ALU forwarded to Aquino’s office a proposal for subsidies in the form of discount cards on goods to minimum wage-earners.

Tanjusay explained that the increasingly large difference between workers’ income and the costs of their needs for daily living ups the number of the underemployed, which he said was at 11 million.

He added that the gap also poses a challenge to the government programs in place for people’s employment.

Labor programs under Aquino

Among these programs are those included in a long list of achievements that the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) boasts of under the Aquino administration.

The list includes the over 8.6 million “disadvantaged” citizens including disaster victims who secured short-term jobs from 2011 to 2014 under the DOLE-monitored Community-Based Employment Program (CBEP).

Baldoz explained that a similar short-term employment program meant “to energize local economies and to provide workers with protection” was first started by Aquino’s mother, former President Corazon Aquino.

“When the administration came into office in 2010, it knew the need for quality infrastructure like roads and bridges, housing, and telecommunication facilities to attract investors, move fast the flow of commerce, and create jobs, particularly in the remote communities. So, the President revived the emergency employment program,” said Baldoz.

More are expected to benefit from CBEP in Aquino’s last year of office, she said. The immediacy of the jobs allowed families to pay for their daily needs.

The Special Program for Employment of Students (SPES) which closed on December 2014 also benefited close to 700,000 poor and deserving students, she added.

They were provided short-term jobs under SPES, which had been allocated a budget that increased yearly since 2010.

“Not only were these young people given the opportunity to earn money to support their education. What’s more important was that they earned or gained the necessary basic skills to prepare them for the world of work,” said Baldoz.

The students under SPES were hired as food service crews, customer touch points, office clerks, gasoline attendants, cashiers, sales ladies, ‘promodizers,’ as well as in clerical, encoding, messengerial, computer and programming jobs.

Baldoz also cited the Single-entry Approach, which DOLE describes as “a 30-day conciliation-mediation alternative dispute resolution system” prior to any filing of labor cases.

Some 7.8 million Filipinos also secured jobs through the state’s placement services under the Public Employment Service Offices.

In 2013, the Labor Law Compliance System which DOLE regards as “landmark reform” replaced the more immediately punitive and enforcement-heavy Labor Standards Enforcement Framework in workplace inspection. (READ: Labor law compliance system is ‘landmark reform’ – DOLE)

Still, the labor law compliance officer (LLCO) to establishment ratio in Metro Manila falls below international standards. There are only about 150 LLCOs for over 37,344 establishments in the region, where population density is relatively higher.

Pending measures

Despite these programs, many labor groups agree that Aquino must fast-track other reforms if he wants a lasting legacy for Filipino workers.

In his remaining year in office, they said job security or addressing the problem of contractual labor must be on his list of priorities.

While certain ILO conventions were ratified under Aquino, including the convention on decent work for domestic workers and maritime labor, the ratification of the convention on public sector unions’ rights is still pending in his office. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.