SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

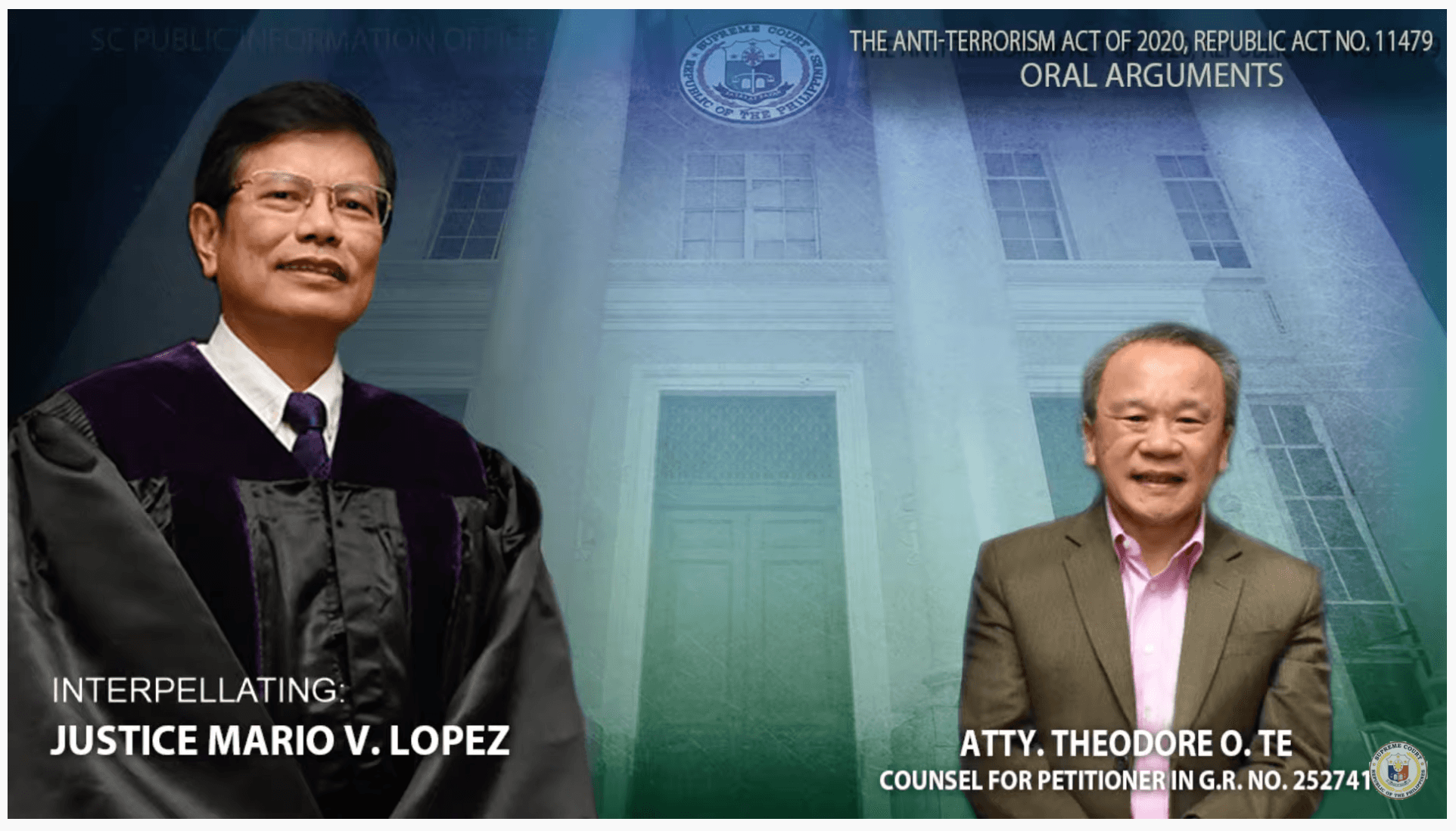

Supreme Court Associate Justice Mario Lopez spent more than an hour on Tuesday, March 2, grilling petitioners’ lawyers on criminal law – his expertise – but still rounded up his interpellations with this point: the need to respect the discretion of Congress when it passed the feared anti-terror law.

“Mayorya na po ang nanalo, sa atin pong Konstitusyon, majority rules. Ngayon, nandirito po tayo upang balangkasin muli ang batas na inyong ipinasa,” said Lopez on Day 4 of the anti-terror law oral arguments, claiming that these were questions of the people.

(Majority won. And in our Constitution, majority rules. Now we’re here to again craft a law you already passed.)

Opposition lawmaker Edcel Lagman tried to explain how minority representatives such as himself expressed reservations and had intended to scrutinize the anti-terror bill further on the floor, but because the bill was railroaded, it didn’t even pass bicameral committee. (READ: House of terror: How the lower chamber let slip a ‘killer’ bill)

A bicameral committee consists of representatives of the Senate and the House who meet to reconcile divergent versions of their bill. There was no such committee for the anti-terror bill because the House of Representatives adopted the Senate’s version in full.

“Alam ‘nyo po, Mr. Justice, kung kayo po ay nasa mababang kapulungan ngayon, maiintindihan po ninyo kung gaano po kagarapal ang super majority at hindi na nabibigyan ng boses ang minority,” Lagman told Lopez, a former Court of Appeals Justice appointed to the Supreme Court by President Rodrigo Duterte in December 2019.

(You know Mr. Justice, if you are in the lower house, you would understand how shameless the supermajority was. They didn’t give voice to the minority.)

Lopez said the issue may be a political question, a legal principle wherein the Court defers to the wisdom of the legislative or executive. “Maybe it’s a political issue which the Court cannot address,” said Lopez.

Lagman said the anti-terror law is a question of constitutionality, which is why the Supreme Court must act on it.

“Kaya po kami dumudulog dito sa Korte Suprema para ayusin ang sistemang iyan at upang i-invoke ang expanded judicial power of review ng Korte Suprema,” said Lagman.

(Which is why we’re running to the Supreme Court for you to fix this system, and to invoke the power of expanded judicial review.)

The Constitution gives the Supreme Court the power of expanded judicial review, or the authority to review the acts of its two co-equal branches of government. (READ: Anti-terror law oral arguments: Can Duterte, Congress be left to own discretion?)

Discretion to legislate general laws

Lopez then interpellated former Supreme Court spokesperson and law professor Ted Te, who, like the justice, is an expert on criminal law. Te stood in for Chel Diokno.

Lopez grilled him on the issue of whether intent can be punished. Petitioners have repeatedly questioned the danger of the law punishing intent, saying it is too vague and open to abuse.

Lopez said that in general, a preparatory act for the commission of a crime is not a crime itself. For example if you buy poison with an intent to kill someone, the act of buying poison is not a crime if you haven’t killed yet, or didn’t kill at all.

But, Lopez said, the exception is, if there is a law that specifically punishes the preparatory act. The example being the anti-terror law, which punishes preparatory acts such as planning, threatening, inciting, and recruitment for terrorism.

Lopez asked Te: Does Congress have the power to legislate in a way that broad preparatory acts are punishable?

Te said, “They can exercise that power, but it does not mean that it will survive constitutional review.”

Like in other interpellations, Lopez kept interrupting Te to get to his point.

“I am not talking about constitutionality, just necessity to justify the penal application of a preparatory act,” Lopez said.

“Compelling state interest requires so…Even a mere tendency, a mere imminence of such crime, the legislature can already stop, or otherwise we might be left behind. Remember in this fight in terrorism, we should have the upperhand, one step ahead of the terrorist, otherwise if we’re behind, we should close shop,” said Lopez.

Te tried to argue that while Congress does have the power to legislate general laws, the power is not absolute, as there is a prohibition on overbreadth.

Lopez didn’t let him finish and again interrupted.

“What I’m saying here is that the legislature should be given the leeway, the discretion to anticipate crimes to be committed in the future. Otherwise, we will be left behind,” Lopez repeated, arguing that the reason the provisions are broad is to ensure that they will cover developing modes of terrorism like bioterrorism or cyberterrorism.

Strict scrutiny

When it came to interpellating University of the Philippines (UP) professor John Molo, Lopez insisted that the government can restrict freedoms if there is a compelling state interest, in this case, fighting terrorism.

Molo, a professor of constitutional law, said that Lopez seemed to forget about the 2nd element of compelling state interest, which is “narrow tailoring.” Narrow tailoring is making the restrictive law so narrow that it only avoids the evil it wants to avoid, and not run the risk of stepping on other liberties.

Lopez had to scold Molo many times, saying the professor was talking ahead of him.

Molo tried to argue that it is the State that is obliged to undergo that strict scrutiny test, to make sure it follows narrow tailoring.

“Binaliktad ko specifically because what is involved here is the state, its interest and security, and not the fundamental law of the land,” said Lopez.

(I reversed it because what it is involved here is the state, its interest and security, and not the fundamental law of the land.)

Molo said, “I would have to respectfully beg to disagree” and began to again explain that the burden is on the state. But again Lopez did not let him finish.

“Professor dakdak ka naman nang dakdak, mamaya in-a-anticipate mo na naman lahat ng sinasabi ko eh. If you disagree, I will give you a chance and this is your chance after I have said everything. File your memorandum to that effect,“ said Lopez.

(Professor you keep on yakking and yakking, you are anticipating everything I am saying.)

Day 4 ended with all justices finishing their interpellation of the petitioners. Solicitor General Jose Calida will have his turn next Tuesday, March 9. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.