SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

In 2006, former vice president Jejomar Binay, former senator Rene Saguisag, former representative Neri Colmenares and former dean Pacifico Agabin were among the 300 or so lawyers who joined an unprecedented march to EDSA Shrine to slam Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s Proclamation 1017.

The human rights lawyers return, collectively called as the revived Concerned Lawyers for Civil Liberties (CLCL), joining forces against President Rodrigo Duterte’s contentious anti-terror law.

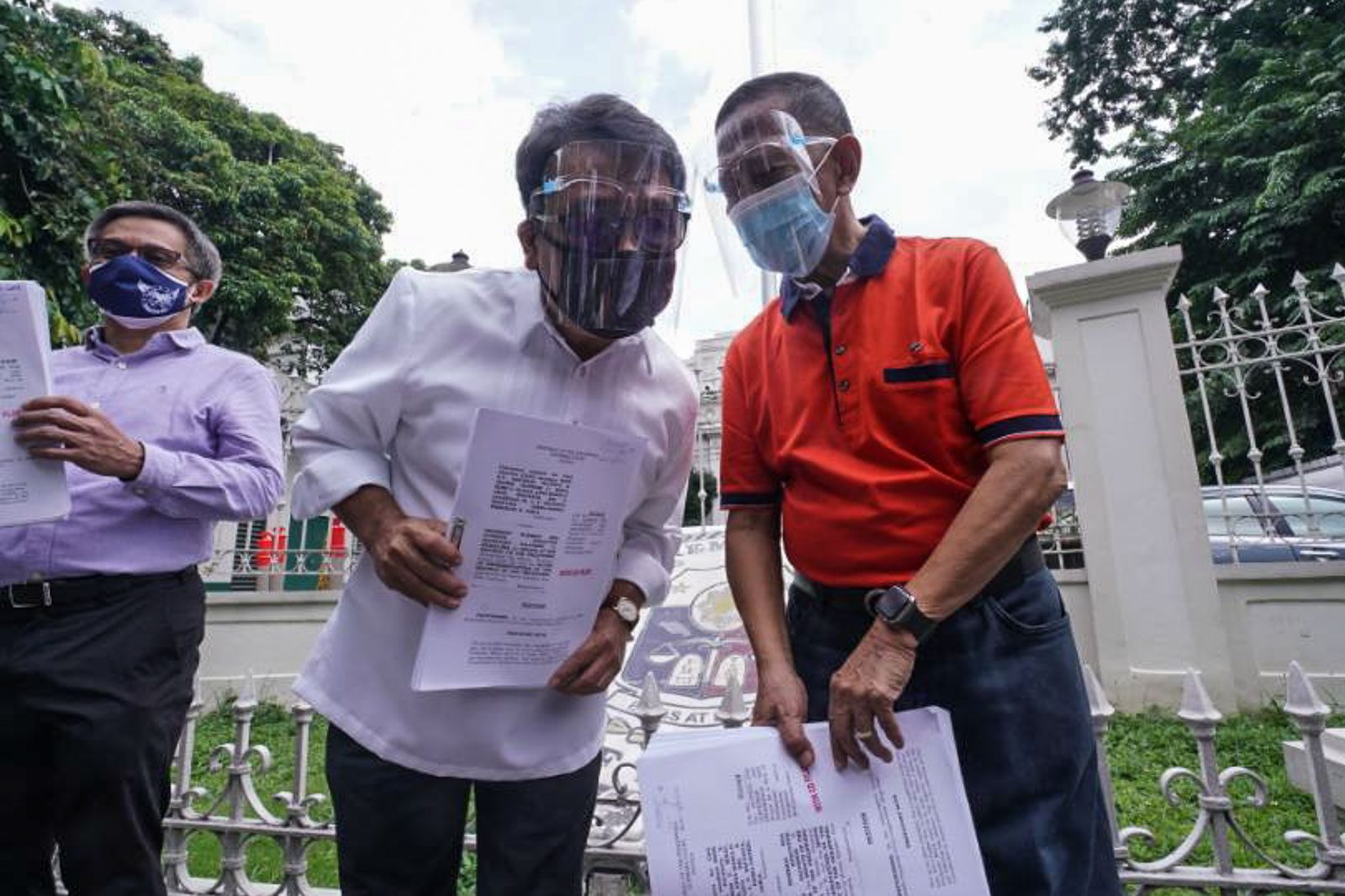

Wearing face shields, Binay and Colmenares led the filing of their petition before the Supreme Court on Thursday, August 6, joined by co-petitioners and fellow lawyers Jojo Lacanilao and Emmanuel Jabla.

CLCL is represented in this petition by former University of the Philippines law dean Pacifico Agabin – a 66-page pleading that compared the anti-terror law to a war-like invasion except that there was no public emergency.

Agabin is also a co-petitioner, as well as National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL) president Edre Olalia, Adamson Law Dean Anna Maria Abad, Sanlakas’ JV Bautista and University of Cebu law professor Rose-Liza Eisma-Osorio.

War-like invasion

The petition said that the law’s authorization of warrantless arrests of suspected terrorists was like the dreaded kempetai or secret police of the Japanese era, when Japanese occupied the Philippines during World War II.

“In that sense it is no different from the Japanese-era practice of kempetai of rounding up suspects fingered by informants, where the only difference now is that they do so not under any hood over the head but in the payroll of the Anti-terror council,” said the petition.

All the petitions – 25 so far – agree that Section 29 of the anti-terror law is unconstitutional for giving the anti-terror council the power of a court to order arrests.

While the rules on criminal procedure allow warrantless arrests in cases of caught in the act, or probable cause to believe a crime has just been committed, the petitions including the CLCL’s argue that the anti-terror council’s standards are too vague to qualify under the existing rules.

“Mere suspicion of terrorism would be enough to make one liable to acquire the ire of the anti-terror council and be immediately subjected to its process of arrest. These suspicions are likely to be based on the legally amorphous products of intelligence reports, which will not pass muster the constitutional requirement for due process,” said the petition.

The petition said the anti-terror council’s credibility was under a cloud of doubt because of the Duterte government’s track record of flawed drug lists which resulted in the execution of thousands of suspects.

“If we go by the previous practice of the current government of coming up with a list of suspected rebels or drug pushers and users, no one would know who prepared the list, or who may be in the list (until one gets arrested, or unless the list gets invariably leaked out to the public), or what may be the basis for being included in the list,” said the petition.

No public emergency

Under the law, suspects could be held for as long as 24 days without a charge.

The Antonio Carpio petition had pointed out that the law’s wording would allow law enforcement to just free a suspect after 24 days and then arrest him again on the same probable cause.

These are contrary to two rules – the Constitution which only allows 3 days in a state of martial law, and the revised penal code which only allows 36 hours in an ordinary state.

The petition pointed out that the anti-terror law made it seem like it was the Second World War when the Philippines created a People’s Court that allowed the State to hold a person as long as 6 months before filing a charge.

Suspects could also be designated as terrorists by the council alone, which could result in the freezing of their assets. A separate and distinct act was proscription as terrorists, which could only be done by a court, but under the law, could be a process as quick as 72 hours without the need for a single hearing.

“The anti-terror law does not present any indication of the existence of some public emergency like those surrounding the creation of the People’s Court by the Philippine authorities after the Second World War that would show the need or the requirement for a special procedure for, and the treatment of, suspected terrorists in the year 2020,” said the petition.

Security officials have complained that the safeguards in the old Human Security Act made it very difficult for them to catch terrorists.

“But it is not the Court’s function, and the Bill of Rights was not designed, to make life easy for police and military agents but rather to protect the liberties of private individuals,” said the petition.

“Police and military agents must simply learn to live with the requirements of the Bill of Rights, to enforce the law by modalities which themselves comply with the fundamental law,” the petition said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Sara Duterte: Will she do a Binay or a Robredo?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/tl-sara-duterte-will-do-binay-or-robredo-March-15-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Political terrain in Taguig has shifted](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/11/binay-cayetano-taguig-november-22-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[ANALYSIS] The race to May 9: Can Robredo do a Binay?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/04/tl-is-there-enough-time.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.