SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

COTABATO CITY, Philippines – The post on Ayrie Ching’s Facebook profile started with a letter:

Dear Career Move,

We’ve been at it for three months and I’m thankful for our time together. I do sometimes wish you didn’t have to take me far from those I love, but I guess there is a lesson in everything. What thrives despite distance is worth the effort to reach out, for one.

Love,

Me

Ching wrote that post in 2012 and uploaded a picture of herself in a veil among members of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). It was taken in Camp Darapanan the day the Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro was signed.

What she remembers most about that day is the image of an MILF member who was crying as the speech of MILF Chair Al Haj Murad Ebrahim was broadcast and heard throughout Camp Darapanan:

“Today we are here to put an end to the adversarial relationship between the Bangsamoro and the Philippine nation. Today it humbles me to say before you, we stayed our course, perseverance has prevailed.”

She remembers because she found herself crying, too.

Back then, Ching had just packed her bags and moved from Manila to Cotabato City to work as a Communications Officer at the Mindanao Human Rights Action Center (MinHRAC).

As she recalled, her journey started with a picture in a newspaper of a woman in a veil and the two words followed by a question mark that accompanied it.

The two words read: Security risk?

The story was about President Benigno Aquino III congratulating the new members of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) Regional Assembly at Malacañang Palace. One woman he shook hands with was wearing a niqab, a traditional Muslim dress that covers the entire body with only the eyes visible through a horizontal opening.

The incident so incensed Ching that she wrote an article about the incident, explaining the different Muslim attires for women.

After the article was published, one of her sources messaged her on Facebook. What started out as a casual conversation suddenly turned serious when she was asked if she wanted to work for a human rights organization based in the Bangsamoro.

Ching said she would consider the offer, but she already knew her answer.

She left Manila on June 12, 2012 – Independence Day.

Nowadays, Ching wears her love for the Bangsamoro on a much more public space than her sleeve: her Facebook page. In a Facebook album called, “Postcards from Mindanao“, Ching chronicles her life in the region, with detours to other parts of Mindanao.

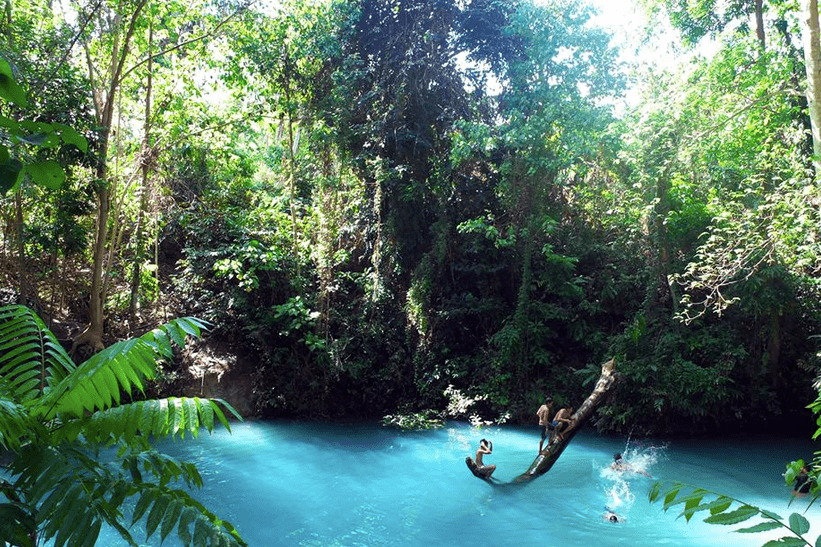

Photos of tranquil verdant mountains in Upi (Cotabato), hidden lagoons in Datu Odin Sinsuat and crystal clear waters of Sultan Kudarat are interspersed with a bamboo hut on stilts near MILF territory in the Liguasan Marsh, young mothers breastfeeding their newborns in squalid displacement camps, and crouched elderly women who struggle with the hopes of seeing peace in their lifetime.

Through these pictures, Ching wanted to show others what every day life is like in Mindanao, especially in the Bangsamoro. It was also a way for her to reassure friends and family that she is safe and happy, despite their reluctance to accept her decision to move.

“It’s nice to live here. It’s quiet compared to Manila,” she said, recognizing that even this is a double-edged sword. The beauty of Mindanao should not drown out the suffering of its people and the cruel irony of living a life of uncertainty and destitution in a place that is so incredibly beautiful.

Heartland

Ching moved back to Manila after a year with MinHRAC, but it was not long before her heartstrings pulled and tugged her back to the Bangsamoro.

Currently, Ching is working as a senior writer at the Bureau of Public Information-ARMM. Part of her job is to write features and human interest stories in hopes of giving a face and voice to the Bangsamoro as the peace negotiations continue.

She continues to add to her album “Postcards from Mindanao” but also regularly posts status updates on her profile page which now serves as a blog of sorts.

On most days, Ching posts news and historical bits about the Bangsamoro – the war that has been going on there for more than 40 years, the massacres during the Martial Law era, and how innocent civilians bear the burnt of conflict and its consequences.

Her detailed commentaries call for readers to understand the issue better, to think about the civilians whose lives are filled with uncertainty, constant displacement and fear.

Her posts are not always welcomed by others, especially during the heated tension that followed the death of the 44 Philippine National Police Special Action Force (PNP-SAF) officers.

“I have been accused of being brainwashed, of being an MILF supporter, even a terrorist,” said Ching. “But I have heard and seen how hard it is for people here to establish lives and careers when moving is a matter of life and death – where you are constantly displaced because you need to survive.”

“Many times I’ve had to talk to survivors and every time I listened to someone recounting how he survived a massacre or how hard life has been for him because of the war, it would be like hearing it for the first time. Always.”

And here tears begin to fall and Ching apologizes. “I always get like this when I talk about the Bangsamoro. It’s either I get sad or angry, even though I’m very thankful to be there.

She composes herself and tries to sound like the 27-year-old she is with the typical problems of a 27-year-old.

“Every time I complain that I don’t have money, that I don’t have a love life,” she chuckled in spite of herself, “I’m quick to remind myself that there are people who don’t even know what they are going to eat today or if they’ll be staying in the same house tomorrow.”

“People tell me, ‘Ang lakas ng loob mo to live there (You’re so brave to live there),” she said.

“Me, brave? When I visit the evacuation centers and bid the displaced farewell, they always tell me ‘Ingat ka’ (Be careful and take care). And I’d think, wow, these people who don’t have a roof over their heads have hearts big enough to be concerned about me. They have shown me what it really means to be brave.”

A Christian who studies Buddhism in her spare time and born to a Filipino-Chinese family, Ching’s affinity to Mindanao, especially the Bangsamoro and its people, transcends her own religion and roots.

It is borne out of her choice to call Mindanao home, and the Bangsamoro that welcomed her will always be her heartland. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.