SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

More victims of President Rodrigo Duterte’s drug war from “all over the country” have sent their representations to the International Criminal Court (ICC), but as the process progresses, the need for their safety becomes more paramount.

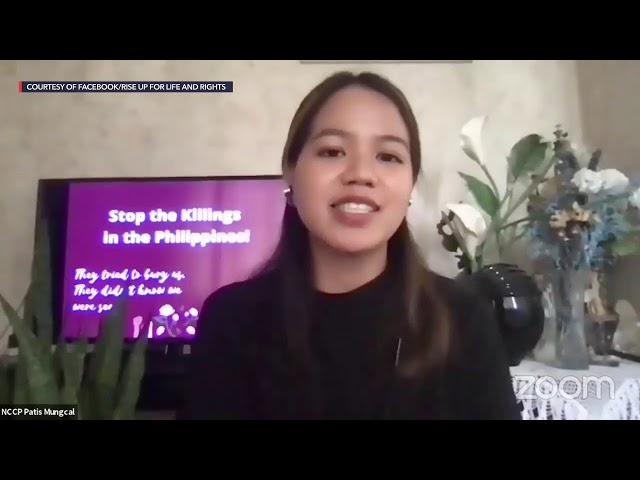

“The representations are more than the original seven who filed the communications in 2018. The seven are openly talking, but the others, we cannot disclose yet. It was all over the country, and many submitted,” said lawyer Neri Colmenares in Filipino during an online forum on Monday, August 16.

The representation process is a phase where the ICC asked victims to send in their “views, concerns and expectations.” It is not yet an indication of willingness to participate in the formal process. The submission period opened after now-retired prosecutor Fatou Bensouda requested the pre-trial chamber (PTC) to open a formal investigation. It ended Friday, August 13.

There is a history of ICC witnesses being harassed, killed, and intimidated into retracting, which, in the case of Kenya, became so bad it forced Bensouda to withdraw the charges.

Colmenares, chairman of the National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL), represents the group Rise Up, which filed one of the dozen communications to the ICC. The Rise Up communication was signed by seven relatives of drug war victims.

Colmenares said they have taken “all efforts” to secure the people who sent representations through them, but “you know President Duterte, you cannot control him.”

“We would appreciate any support and help from the other institutions. Hindi basta-basta si President Duterte (Duterte is not an easy person to go up against),” said Colmenares.

Llore Benedicto Pasco, who lost two sons in a police anti-drug operation in 2017, said they are prepared for the long haul.

“Alam naman naming mahabang labanan, matagal, ngunit talagang gusto namin ay hanggang sa dulo lumaban,” said Pasco.

(We know this is a long fight, but we want to see it through the end.)

Under the ICC’s chambers practice manual, the PTC judges have 120 days to decide on the prosecutor’s request to open the crucial phase of investigation. That 120-day period ends by end of September, although some experts believe it can be as short as three months or by the end of August.

Families, however, have been cautioned against this expectation.

“It can be anywhere from three months to a year. We have to be patient because we don’t want this to be dictated by the same rules that the Duterte government has followed in killing many of our countrymen – which is that there was no due process,” said international law professor Tony La Viña, also a convenor of the legal coalition Mga Manananggol Laban Sa Extrajudicial Killings or Manlaban Sa EJK.

ICC prospects

Kristina Conti, lawyer for Rise Up, said some of the victims who sent representations are willing to participate in the potential trial, their resolve strengthened through the years, and encouraged by the developments in the ICC that Pasco described as “light” after a long period of darkness.

The others, however, have just started to join the efforts, many of them relatives of those killed by unidentified gunmen or vigilantes. Vigilante killings are hard cases, although Bensouda’s request made strong claims that policemen outsourced the killings to vigilantes, all part of an “apparent state policy” under Duterte, she said.

Their apprehensions, Conti said, also stem from the fact that they barely have documents pertaining to the killings – a problem in the drug war so widespread that even government agencies like the independent Commission on Human Rights (CHR) is not spared.

The Department of Justice (DOJ), tasked by Duterte to lead a review, is settling for documents on only 52 out of the 7,000 deaths in police anti-drug operations.

“We’re trying to get ready [if ever the ICC sets up a base here], in one case, they assigned a permanent ICC personnel in that country and that country representative is the coordinator, we are preparing for that as well. Rise Up has a Cebu office, so we’re trying to coordinate with lawyers who can institutionally represent victims,” said Conti.

Colmenares said the recent move of new ICC prosecutor Karim Khan to negotiate an agreement with Sudan to turn over their former president Omar al-Bashir is encouraging.

However, the development in Sudan came only after a new transitional government was elected by the Sudanese people. They ousted al-Bashir through a series of protests driven by the country’s economic problems.

Colmenares said the accountability for human rights “will definitely” be part of the conversation for the 2022 elections.

“Many people will demand that the next president will ensure that he or she will not block an ICC investigation,” said Colmenares.

“It is inevitable for President Duterte because among his crimes is not only his COVID-19 response, it’s not only the economic conditions, poverty, it’s also human rights,” said Colmenares.

– Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[The Slingshot] Alden Delvo’s birthday](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-alden-delvo-birthday.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=263px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.