SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The assumption was lessons were learned from Tropical Storm Ondoy (Ketsana) 11 years ago, and riverine areas like Marikina, Pasig, and parts of Rizal would no longer be caught off-guard by a sudden deluge from sustained torrential rains.

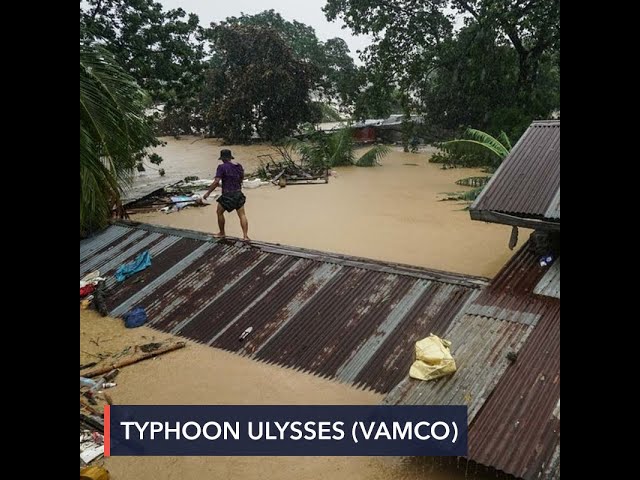

And yet on Thursday morning, November 12, pleas for rescue poured in after Typhoon Ulysses (Vamco) unleashed its fury on these same areas overnight. Social media sites were flooded with pictures of inundated villages with rooftops barely peering through the water’s surface, with captions from frantic relatives checking on their loved ones.

Why so many people were caught in this deja vu was the question Assistant Secretary Casiano Monilla, deputy administrator of the Office of Civil Defense (OCD), faced in the agency’s first media briefing on Thursday.

The OCD is the implementing arm of the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC), the country’s nerve center when responding to calamities such as typhoons and earthquakes.

Monilla said rescue operations were underway in Central Luzon, Metro Manila, Calabarzon, and Bicol even as Ulysses continued to lash at these regions. Officials had their eye on areas near bodies of water, and those that will be flooded when the Angat, Ipo, La Mesa, and Wawa dams release their overflow of rainwater funneling through them from the Sierra Madre.

All military assets in Metro Manila were deployed to rescue operations, as well as units from other uniformed services, said Monilla. He declined to give specifics, as the agency was still gathering data from the ground, he said.

Monilla thanked the media for their coverage, saying the government is able to get real-time information through their reports.

People from known flood-prone areas have been evacuating over the past two days, Monilla said. All the necessary warnings and notifications of storm hazards were sent directly to the public and to local governments days in advance, he added.

“So we were not actually caught flat-footed by this event,” Monilla said, responding to questions from reporters in the virtual briefing on Thursday morning.

Protocols observed

The OCD and NDRRMC followed all the protocols for preparing for typhoons, he added. The quick succession of typhoons – Pepito (Saudel), Quinta (Molave), and Rolly (Goni) – that went before Ulysses had put everyone on their toes.

Two pre-disaster risk assessment (PDRA) meetings were held on November 7 and 9, to prepare for Ulysses, according to NDRRMC spokesperson Mark Cashean Timbal. Both PDRAs were attended by various national government agencies and regional disaster councils, he added.

NDRRMC Executive Director Undersecretary Ricardo Jalad told reporters in a message that the PDRAs covered evacuation plans and Ulysses’ potential to cause devastation. The Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) also issued a memo to activate Operation Listo – the protocol in responding to typhoons.

Because to “micromanage” every locale’s response to a typhoon would be unwise, Monilla said local government units (LGU) are primarily and largely in charge of shepherding their constituents before, during, and after typhoons.

This includes identifying which communities would be vulnerable to an oncoming storm, calling for evacuations – forced evacuations, if necessary – and managing the aftermath.

But for Ulysses, the national government enlisted help beyond LGUs.

“Knowing our current handicap in communications because of the effect of Super Typhoon Rolly, we used the communication systems of the Philippine National Police, Armed Forces of the Philippines, and other agencies to ensure the information reached the community,” Jalad said.

But why were so many people still caught unawares? Why were they reliving the trauma from Ondoy in 2009?

“Kung minsan lang po kasi, ‘pag nag-ikot ang mga local officials, hindi kaagad sumusunod ang mga kababayan natin. Kumbaga, mas nagre-rely tayo sa kung ano ang ating nararamdaman o ang prevailing na sitwasyon na ating nararamdaman other than the advice na binibigay ng PAGASA (Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration),” said Monilla.

(Sometimes, when local officials make their rounds, our countrymen don’t always follow instructions right away. In other words, we rely more on what we feel or the prevailing situation that we see other than the advice being given by PAGASA.)

When vulnerable residents are warned before a typhoon – when the skies are still clear and the weather, calm – they tend to ignore it. When the storm begins its onslaught, it is often too late to evacuate, and victims end up stranded and needing rescue, he added.

‘No time to point fingers’

Reporters asked Monilla whether forecasts from PAGASA were relayed to the people and whether those warnings were detailed enough to warn them of the huge amount of rain Ulysses could bring.

“The limitation, really, of science would be the volume of the rains that come with these typhoons. We can predict the strength, speed and gustiness, but the volume of rain – it is only known once the typhoon touches down,” Monilla answered.

Forecasts and warnings were sent to peoples’ mobile phones, and posted on the social media pages of different government agencies. The question is, was it made clear to communities exaclty what storm signal numbers and other advisories meant in terms of wind, rain, and potential for destruction?

That is largely the local governments’ job, Monilla said.

But what’s done is done and at the moment, the OCD’s focus is on rescue operations and issuing warnings about further effects of Typhoon Ulysses, including spillage from dams.

“I guess it’s not time for us to point fingers, sorry to say that, but we are focusing now on the conduct of the rescue operations. Let us finish the operations. Let’s save lives first, then saka na siguro natin pag-usapan ‘yan (then perhaps we can talk about that afterwards),” said Monilla.

But if so much depends on LGUs, is the OCD or NDRRMC overseeing their compliance with disaster protocols? What would it take to prevent yet another deja vu of a deluge from a storm?

“With the help of DILG, there’s a need to revisit siguro (perhaps) the compliance of our local governments when it comes to that,” said Monilla.

“Tingnan natin ano talaga ‘yung mga decision points na hindi pa nagagawa to prevent occurrences na gaya nito, na another emergency (Let’s look at what really were the decision points that failed to be made to prevent occurrences like this, yet another emergency),” he added. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] Lessons in resilience from Japan’s New Year’s Day earthquake](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/01/TL-japan-earthquake-warning-system-jan-3-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.