SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

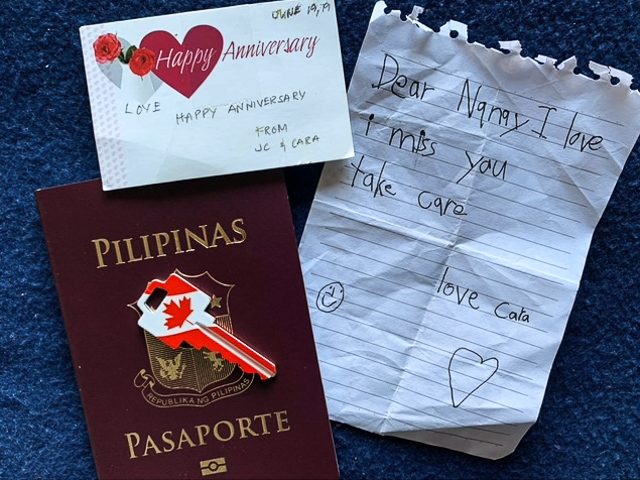

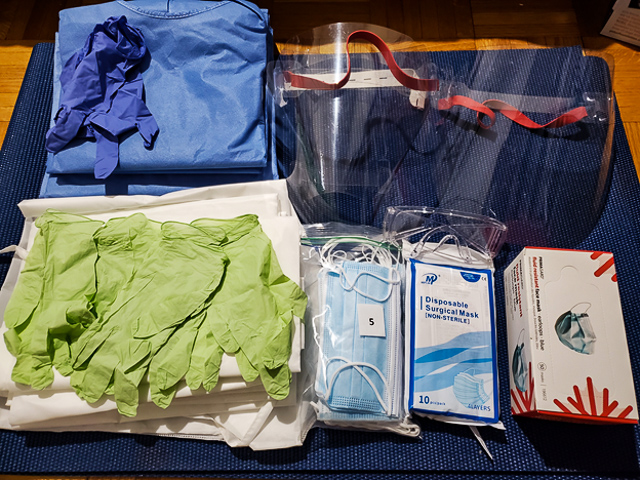

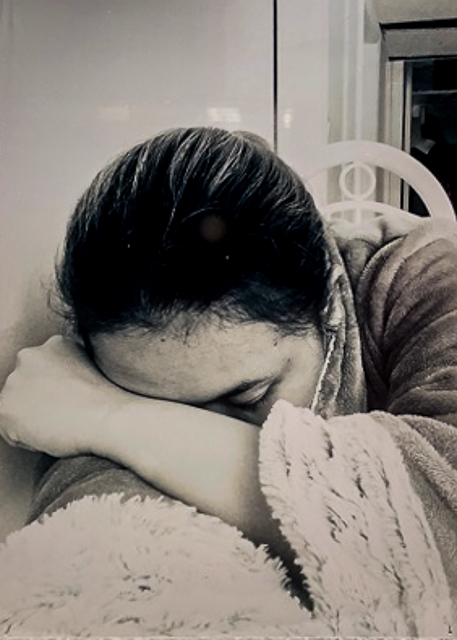

A wooden table set for one, surrounded by six empty chairs. A child’s letter handwritten on paper torn from a notebook that reads: Dear Nanay, I love I miss you. Take care, love, Cara. A key designed with a Canadian flag on top of a Philippine passport. A hospital frontline worker in full personal protective equipment (PPE), sheer exhaustion written on her face while staring at the camera.

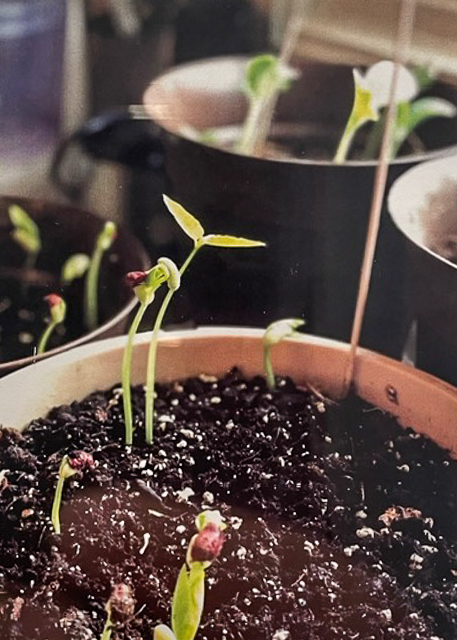

These are some of the poignant images captured in “Matatag: Filipina Care Workers During COVID-19,” a photo series by Filipina nurses, personal support workers, and live-in caregivers, currently on exhibit at A Space Gallery in downtown Toronto.

The window exhibit, which captures everyday moments of Filipina care workers, is part of a participatory arts-based research project by a team of Filipino-Canadian scholars, researchers, and community organizers from Gabriela-Ontario and Migrants Resource Center Canada.

Ethel Tungohan, associate professor and Canada Research Chair at York University, said the team embarked on the project after noticing that while essential care workers, many of them Filipinos and Filipino-Canadians, were among those hit the hardest by COVID-19, they were invisible in the news.

“I found that even within my own family, some of whom are care workers, we were getting affected by COVID. I had an uncle who got COVID and had to be brought to the ICU,” she said.

In March, Manitoba released data showing the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on Indigenous, Black, and Filipino-Canadians, a pattern that its chief provincial public health officer, Dr. Brent Roussin, said was repeated in other provinces across Canada. Filipino-Canadians accounted for 12% of cases in Manitoba, despite representing only 7% of the population. Most are frontline workers – those who work in the healthcare sector and in low-wage sectors such as food services, cleaning services, domestic childcare, and seniors’ care.

Tungohan, the project’s principal investigator, said the team decided that the best way to “actually dive into people’s intimate everyday experiences” was to use art. “It’s not going to be as cathartic if we just had a conversation, right?”

They used photovoice, which involves participatory photography, discussions, and digital storytelling for advocacy projects.

“What’s interesting about photovoice is that it’s really meant to bring the experiences of people to policymakers, and that’s what our main goal really is,” said Mauriene Tolentino, a researcher from Gabriela-Ontario.

“We want to understand how care workers have been faring during COVID. What are their goals? What are their dreams during this time? But also, what are the challenges that come with being a care worker during the pandemic?”

‘Kuwentuhan sessions’

With support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, a federal research funding agency, the team was able to provide honoraria to 78 care workers who participated in the research by taking photographs and joining online kuwentuhan sessions that included discussions about issues they are facing.

Among them was Shirley,* a live-in caregiver, who said the research was “a blessing” because it provided her with a much-needed connection that was lost when households were asked to shelter in place for months because of COVID-19.

“I’m really sociable, so it was hard” not to be able to gather with friends, said Shirley, who requested that her real name not be used for fear of losing her job. It didn’t help that because of the pandemic, her wedding in the Philippines had to be postponed twice; she also hasn’t heard back about her application to become a permanent resident.

Shirley and her 15-year-old daughter who lives in Bulacan were hoping to be reunited this year.

“Masakit siyempre, lalo na sa bata na umaasa (It’s painful, of course, especially for a child who was hoping for it to happen),” she said.

Shirley wondered why it takes long for families of live-in caregivers to be reunited despite the fact that family reunification has been touted as a cornerstone of Canada’s immigration policy.

“Refugees and live-in caregivers wait much longer for family reunification than people in the Family Class,” according to the Canadian Council of Refugees (CCR).

CCR and other nongovernmental organizations like Migrante have been urging the federal government to allow spouses and children of Temporary Foreign Workers (including live-in caregivers) to accompany them in Canada. If families are reunited, it will benefit society in the long run, stressed Shirley.

“We will all work. I will dedicate my life to Canada,” she said.

A lot of the stories shared during the kuwentuhan sessions of the project were about challenges and problems that have been there for a long time “but the pandemic just magnified” a lot of them, said Tolentino.

These include long hours of work, much of them unpaid, for live-in caregivers who are unable to leave because their employment status and future as permanent residents are tied to their employers.

“Employers are not held accountable” for extra hours worked, she stressed. The pandemic has also made days off non-existent, since employers often forbid live-in caregivers from leaving the household, citing safety reasons.

One way of holding employers accountable would be to have them register with Employment Standards established in every province, said caregiver participants, adding that foreign recruitment agencies should also be mandated to obtain a license from the same body. A national caregiver union would also help increase workplace health and safety protections, they added.

Participants identified other issues and offered recommendations that researchers outlined in a policy brief. They included calls for “equitable immigration policy changes,” including reduced wait times for reunification, a simpler application process, and removal of language and educational requirements, described as “discriminatory, costly, and inaccessible to Filipino caregivers.”

Caregivers applying for permanent resident status pay a fee of $1,050 and are required to pass the International English Language Testing System or IELTS exam, which costs about $300. An additional $1,050 is paid when sponsoring a spouse or partner; $150, for every child sponsored. A biometric fee of $85 per person is also required.

‘Essential workers or sacrificial workers?’

Tungohan said what struck her the most about the initial findings of the still-to-be-completed research was “the intersection between immigration and labor challenges” especially for those under the live-in caregiver program.

“What was startling to me was that all the care workers we talked to had experienced heightened anxiety and stress” during the pandemic. There were frustrations around the lack of paid sick leaves, the absence of pandemic pay for temporary workers, stalled open work permit applications, the labyrinthine process of applying for permanent resident and other visas, and barriers to permanent residency.

“One of the things that really is appalling for me is the fact that the rhetoric of heroism doesn’t actually mean the care workers are protected,” she said. “Why are we presenting more barriers for care workers to get permanent residency when we recognize their labor contributions especially during a pandemic?”

She added that care workers themselves are asking, “Are we really essential workers or sacrificial workers?”

Tolentino said having the care workers themselves be the researchers and photographers for the project was intentional.

“They are the ones that hold the knowledge, they are the ones with the photos, and the photos are the data,” she said. “What we really want this project to be is for their voices and their stories to be at the center of everything.”

Participants used whatever was available to them, in most cases, their cell phone cameras.

“That actually was pretty powerful because for many of them, that was accessible,” she said.

Being able to share their photographs and stories in a safe space that was meant for them was also helpful.

“A lot of them were shocked and surprised that their experiences are not unique. A big component, too, was that the feeling of isolation was no longer there when we came together,” said Tolentino.

Shirley agreed, saying the virtual meetings with care workers helped her realize she wasn’t alone, and it improved her mental health during the pandemic.

Apart from the exhibit, which ends in January 2022, the photographs and stories will be showcased and stored on a dedicated website that also includes a petition encouraging people to support care workers and nudge policymakers.

After all, as Tungohan stated: “These are not just a bunch of pretty pictures. [They’re] meant to catalyze social and political change.”

She noted that the photographs care workers contributed highlighted not only their concerns and challenges but also their steadfastness, hence, the exhibit title, Matatag. There, in the midst of photos showing PPE, to-do lists, and work items are images of plants being cared for, containers of food meant to be shared, cans of Spam, Tim Hortons ground coffee, and cereal being packed for a balikbayan box to be sent back home.

“People were still able to build community and still able to think about the ways that they can support each other, support their friends, and support their families. And also fight back,” observed Tungohan. “Even as these women were facing challenges, there was still a lot of hope that things will get better.” – Rappler.com

Marites N. Sison is a freelance writer and editor based in Toronto. She can be reached via Twitter and Instagram: @maritesnsison

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Limited intake of international students: Is Canada knee-capping its future?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-canada-forgeign-student-cap-02232024-2.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.