SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This story is part of COVID-19 Pushed Me to Leave the Philippines, a series of profiles of Filipinos who migrated out of the country during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Earl Beran had no plans of migrating out of the Philippines.

His life after graduating with a degree in electronics engineering in August 2020 consisted mostly of helping his humble family business in Nueva Vizcaya. He had also put up his own food and drink business.

But because of pandemic restrictions that were tightened and prolonged, and the difficulty of finding a job in his own country, he now finds himself working as a teacher in Bangkok, Thailand.

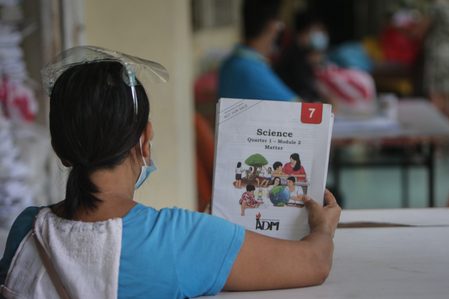

In the Philippines, most children are unable to come back to their classrooms. In 2021, the country became the last in the world to resume face-to-face classes since COVID-19 was declared a pandemic – and only for a handful of schools in areas deemed low-risk for the coronavirus.

Earl gets to spend his time teaching kids aged 6 to 12, whose joy he witnesses every day as they get to learn and play with their classmates. Thailand opened its classrooms in mid-2020.

If only the kids at home could experience the same, he says.

When a Thai opportunity came first

Nueva Vizcaya had fairly loose restrictions during the several months it was under modified general community quarantine (MGCQ) – the least strict of the government’s former quarantine system. Then, when a fresh surge of COVID-19 cases swept the country, the province was put under the stricter GCQ in April 2021.

“At first, booming [ang negosyo], pero noong nagkaroon ng cases, humigpit lalo ‘yung restrictions and I decided na stop muna. Natambay ako, and doon ko na-feel kung gaano kabagal ‘yung pacing ng buhay. So I decided to look for job opportunities na meron,” he said.

(At first, my business was booming, but when cases started to pop up, the restrictions were tightened, and I decided to stop for the meantime. I had nothing to do, and that’s when I felt how slow my life’s pacing had become. So I decided to look for job opportunities that were available.)

In the first quarter of 2021, the Philippine Statistics Authority announced that the country’s gross domestic product shrank by 4.2%, marking the longest recession in recent history.

Earl tried applying for engineering jobs and internships, full time or part time. He was able to name two companies he applied for, but forgot the rest because of how many applications he sent out.

He also explored a teaching opportunity in Thailand in a school where his aunt was an investor.

“Walang nag-co-confirm. From that moment, sinabi ko sa sarili ko na kung sinong mauunang mag-co-confirm, doon ako,” Earl said. (Nobody was confirming. From that moment, I told myself that whoever confirms first, that’s where I’ll go.)

It was the Thai school that accepted him first. While his aunt referred him, she had no involvement in the hiring process. Earl was hired for his own merit, he believes.

“But I acknowledge the fact that I was privileged to have the opportunity, and I did my part by ceasing it,” he said.

Earl’s father was initially against his move, but slowly showed his support. One day, his father told him that it was okay to chase his dreams. “That’s what gave me strength to move forward,” Earl said in Filipino.

He was on his way to Thailand in June, but not without tears in his eyes as he left for the airport.

Learning from the kids

The electronics engineering graduate had expected to work in telecommunications, doing site visits and managing projects. But now, to his own surprise, Earl finds himself teaching math and computer-related subjects for 6- to 12-year-olds.

“The first day was chaotic,” Earl recalls as he began his teaching stint in August. “Para akong nangangapa sa dilim (I felt like I was grasping in the dark).”

His first day of teaching also happened to be the day he got the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. The day consisted of enduring the vaccine’s side effects, going to the immigration office for an additional visa requirement, and then meeting the students for the first time.

Despite the early challenges, he grew into his job. In his journey as a new teacher, he realized that he was good with children. He also began to have meaningful experiences with them.

One of the most memorable moments, Earl said, was when he encountered a kid who didn’t want to color in pink. The student said pink “is only for girls and not for boys.”

Earl asked the student why, and the boy said it was what he learned from his father and previous teachers. Then Earl explained that every color is for everyone.

“To my surprise, two days after that, they had another activity with coloring, and he approached me proudly showing his work saying ‘Teacher, look, I used pink and my work looks beautiful.’ Moments like that made me realize na I am doing something good here after all,” he said.

If only in the Philippines

According to Earl, a big part of the reason he left his home country was because the pandemic was affecting him mentally and emotionally. He laments how Filipinos’ lives are negatively affected due to the government’s pandemic response.

“Every time na pumapasok ako sa school, and see the kids enjoying ‘yung experience to study sa school and play with their friends….If only okay din yung response natin diyan sa Pinas, na-e-experience na rin sana nung mga kids sa ‘tin ‘yung ganito,” he said.

(Every time I go to school and see the kids enjoy the experience of studying in school and playing with their friends….If only the [pandemic] response in the Philippines was better, the kids in our homeland could experience this too.)

Thailand had begun face-to-face classes from June 2020, but with a limited number of students per class, and with certain health protocols such as distance between school tables and students not having meals together. In Earl’s school, they practiced blended learning. He handled five students in a room, while others joined classes online.

Meanwhile, in the Philippines, the pilot run for limited face-to-face classes for younger schoolchildren began in November 2021. Issues with distance learning, as well as academic freedom also persisted throughout the year.

“Mapapa-’sana all’ ka sa lahat, di lang sa education sector. Di ko maiwasang isipin na, ‘E di sana kung may solid plans ‘yung mga nasa itaas, e di sana okay na din tayo,’” he added.

(It has you saying “I wish this was for all” in everything, not just for the education sector. I can’t help but think, “If only authorities had solid plans, then we would be okay too.”)

Earl has a tentative plan to come back to the Philippines in December 2022. For now, he embraces where life will take him now, and continues to hope for a better situation at home.

“I am excited for the things that I will achieve and discover in myself. For my family and friends, I hope that in the future they will be happy, and may we have a stronger bond,” he said.

“For my country, I am hoping that someday, when I return, everything will be good and that will prompt me to stay and never choose to leave again.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] Mentorship matters](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/mentorship-matters.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Education for life: Weaving ethics in all subject areas](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/Education-for-Life-Weaving-Ethics-in-All-Subject-Domains.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Limited intake of international students: Is Canada knee-capping its future?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-canada-forgeign-student-cap-02232024-2.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Rappler Investigates] Who’s fooling who?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/rodrigo-sara-duterte-2019.jpeg?resize=257%2C257&crop=167px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.