SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

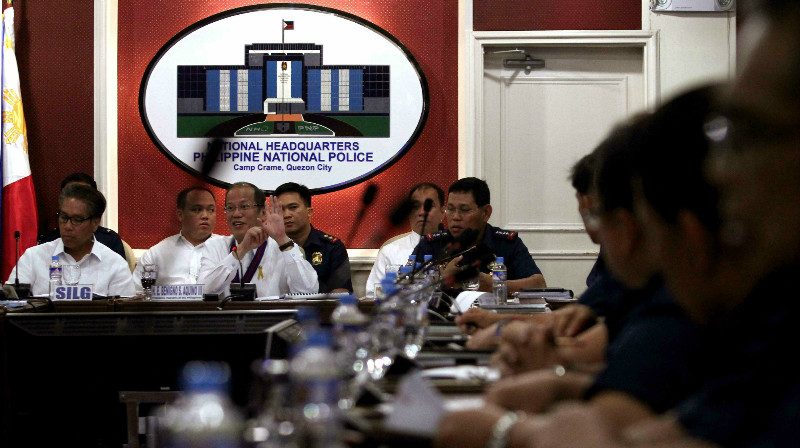

MANILA, Philippines – Who called the shots that led to the January 25 carnage in Maguindanao? What prompted a special operations team, which is trained for surgical strikes, to attack a rebel stronghold without help from territorial ground forces that are more familiar with the terrain? Why was this plan kept secret from the Philippine National Police (PNP) high command and other government security forces?

The Special Action Force (SAF) operation against top terrorists – alleged Malaysian bomb maker Zulkifli bin Hir, better known as “Marwan,” and Abdul Basit Usman – caused the death of 44 SAF troops and the wounding of 16 others, including 3 civilians.

Government officials said Marwan was killed in the attack and that Usman was able to escape. We were shown a photo of a supposed dead Marwan by officials, but government has not officially released it. Even President Benigno Aquino III, in his televised address to the nation on Wednesday, January 27, was not categorical.

“In the encounter that followed, the primary target, Marwan, was allegedly killed,” he said. Marwan has a $5-million bounty on his head, courtesy of the US Federal Bureau of Investigation.

At least 5 facts have been established in the aftermath of the incident, based on our interviews with police officials, military officers and government authorities, as well as their public statements.

- The plan to arrest Marwan and Usman has been in place since the botched US-backed military operation in Sulu in February 2012, that targeted – but missed – Marwan. The military prematurely declared then that they had killed him. In August 2014, however, a senior military commander in Cotabato admitted that intelligence agents had spotted Marwan in central Mindanao.

- Various security units were involved in the hunt for Marwan – operating either independently or in coordination with each other. In the case of the PNP, this was a project supervised by suspended PNP chief Director General Alan Purisima. The President himself admitted this on Wednesday, but hastened to add Purisima ceased to be involved when the Ombudsman suspended him on December 4, 2014. At least two sources told Rappler that Purisima’s name was mentioned in a closed-door meeting of top officials in Cotabato last January 26. We learned that the regional police office of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), headed by then Chief Superintendent Noel de los Reyes, was also focused on getting Marwan. Closely associated with Purisima, De Los Reyes retired only recently, in December 2014, leaving just an officer-in-charge (OIC) in his post. The sacked commander of SAF, Police Director Getulio Napeñas Jr, is a classmate of De Los Reyes at the Philippine Military Academy (1982).

- The acting PNP chief, Deputy Director General Leonardo Espina, learned about the operation only after the SAF units had entered Mamasapano, Maguindanao. Espina disclosed this last January 26, on the day they announced Napeñas’ relief. Napeñas himself admitted this in an exclusive interview with the Inquirer published on January 29. He said he informed Espina about the Mamasapano operation through a text message at 5:30 am Sunday. The operation began at 2:30 am. (READ: SAF kept military out of the loop)

- The confidence of SAF about Marwan’s whereabouts was due to US intelligence provided to the elite team. It was the US-trained 84th seaborne battalion of the SAF that was deployed to get Marwan. Unfortunately, the ground forces of SAF under the 5th special action battalion, which were deployed as the blocking force that would facilitate the exit of the seaborne unit after the attack, were the ones who were trapped in heavy gunfire and killed.

- President Aquino was directly in touch with Napeñas, who received orders from his commander in chief to coordinate with the military before the strike.

At least 3 basic questions remain unanswered:

- What was the chain of command for this operation? Who acted as the supervisor of the SAF commander in the crucial hours before he made the decision to attack?

- Why did the SAF commander defy the President’s orders to coordinate with other government forces?

- Were the SAF commandos prepared to act on the intelligence they gathered?

Soldiers and police personnel follow a clear chain of command. It’s a given in the security community: your boss gives you orders that you are mandated to follow.

Aside from now Napeñas Jr, who else gave the go-signal for the January 25 operation?

President Aquino said he “was talking directly to the SAF director.”

Left out of the loop were the PNP’s OIC and concurrent Deputy Director General for Operations Deputy Director General Leonardo Espina, and the PNP’s Chief of Directorial Staff Deputy Director General Marcelo Garbo Jr.

Civilian officials, such as Interior and Local Government Secretary Manuel Roxas II, are usually not part of the chain of command in operations like this, but the political implications of the attack on the peace process justifies his questions on why he was not informed about D-Day.

Slightly in the loop, according to Aquino, was Purisima. “If at all, baka ‘yung jargon tinutulungan ako ni General Purisima to understand [the operation] (maybe General Purisima helped me understand the jargon of the operation),” said Aquino when asked if Purisima played a role in the PNP SAF operation.

Aquino said the suspended PNP chief was directly reporting to him about the operation until he was suspended on December 4 last year.

“Tapos after [the operation], if at all, ‘yung siya ang [because he was] very knowledgeable about the whole thing, ipinapaliwanag sa akin ‘yung [he explained to me the] intricacies of what the plan being presented to me was,” added Aquino.

Purisima, currently serving a preventive suspension order over an allegedly anomalous deal in the PNP’s Firearms and Explosives Office (FEO), is a close friend of the President’s. (READ: Aquino, General Purisima and the past that binds them)

His involvement in this operation unmasks yet again the divisions in the PNP: between the Purisima and Roxas camps. The two don’t see eye to eye.

If neither Espina nor Purisima nor Roxas called the shots, who then did? Did the government entrust the high-level operation solely to the 2-star Napeñas?

And even then, how was he able to get a direct line to the President?

The fomer SAF commander, police sources said, is not necessarily known as Purisima’s protégé. But to get the plum post of PNP SAF, you need to be in good graces with the PNP chief.

PNP chiefs, another official said, are most careful about who they appoint to head the thousands-strong SAF and the PNP’s Intelligence Group – the most crucial commands for operations.

Senior police officials told Rappler that it’s not unusual for the PNP’s top officers to be kept out of the loop when it comes to high-risk and high-value operations such as the manhunt for Marwan.

In those instances, cops operate on a “need to know” basis.

Who would normally “need to know?” The PNP chief, definitely. But it appears now that Purisima did not turn over any intelligence reports or operation plans to Espina or Garbo. As OIC, Espina enjoys the “full powers and full authority” of a PNP chief.

Click here to go back

Why was there no coordination with other units?

One of Aquino’s orders to Napeñas was to coordinate with other security forces, the military in particular. “I underscored the need to alert other branches, or their respective heads; the notification must come at the appropriate time, with complete information, for them to make the necessary preparations,” said the President.

It seems the PNP SAF – or at least Napeñas – failed to “make the necessary preparations” that the President wanted. (READ: Inside story: SAF kept military out of the loop)

The Army 6th Infantry Division, whose area of operation includes Mamasapano town, had no idea that SAF troopers were planning to enter the known bailiwick of the MILF, until after the SAF were already there.

The elite police force entered MILF/BIFF “territory” in the wee hours of Sunday morning. Hostilities lasted until sunset, Roxas said in a previous media briefing.

Gaps in coordination – and the subsequent difficulty in communicating during a gunfight – are why it took a while for Brigadier General Carlito Galvez and the rest of the Coordinating Committee on the Cessation of Hostilities (CCCH) to intervene.

MILF and government officials tried to ease the situation, but instructions over the phone do not work in the midst of firefight. The CCCH only managed to enter the area a little after the “most intense” hours of battle happened between 8 to 10 am.

By the time they arrived, bodies already littered the streets.

Why wasn’t the army able to swoop in and prevent deaths? Aquino himself explained.

“The notification to the AFP came too close to the time of the encounter, thus making it difficult to determine if they were given enough time to prepare, had their assistance been necessary,” he said.

Why was coordination so important? The terrain in barangay Tukanalipao, Mamasapano town is tricky. According to police officers familiar with the area, there’s only one way in and out. If you’re trapped, it’s a deadend.

The SAF battalions sent to Maguindanao were war veterans. But they weren’t necessarily familiar with Tukanalipao.

In and out – that’s how the SAF operates. But the blockade group of SAF troopers in Mamasapano were wiped out even before they could try to stop attacking rebel forces.

That’s when the operation crumbled. The extraction plan failed.

“I was surprised to learn that the heads of the Western Mindanao Command, or even of the 6th Infantry Division, had only been advised after the first encounter involving Marwan and Usman; the SAF forces were already retreating, and the situation had already become problematic,” Aquino later admitted.

Were the MILF and BIFF still in cahoots? The whole encounter seems odd to many, especially those who may not understand that while the MILF and BIFF differ on their stand on the peace deal with the government (the BIFF broke away from the MILF because of the peace talks), their is a bond that is (often literally) bound by blood.

Click here to go back

Were the SAF commandos prepared?

The most basic of basic questions: Why the PNP SAF, and why did they do it alone?

Aquino’s answer, in his public defense of the operation, is simple: the police had “actionable intelligence.”

That’s not to say that only the PNP was chasing after Marwan and Usman. The Philippine government’s security sector: the PNP, the AFP, and the National Bureau of Investigation, were all actively trying to hunt down the two terrorists.

Was the SAF ready? SAF commandos are the PNP’s best trained.

They also have the best and newest equipment – night vision goggles, Ultimax assault weapons, that are now in the hands of rebels. Without a doubt, they had the right training and tools to take down the two hits. SAF troopers are also the recipients of the best training – both from the Philippines and abroad.

Still, some SAF troopers in the operation were hesitant about the mission but Napeñas reportedly still gave it the green light, senior police officials said.

A painful question to ask would be: Had they brought in other government forces, would it have ended better? Did the PNP not trust the AFP? It seems old issues may have come into play.

In Maguindanao, for instance, police officials have been frustrated over what they viewed as inaction on the part of the military. The target was there, the intelligence was good, so why weren’t the military chasing them down? Local police tried several times in the past to chase after Marwan, to no avail.

If the sheer number of SAF personnel is taken at face value, it’s clear they had no intention of bringing in other government forces, meaning the military, said one former SAF commando.

“It was a calculated risk,” he added.

The PNP’s Board of Inquiry will have a month to complete its investigation, after which it is expected to come up with answers to these basic questions, and more.

The Senate is also set to hold its own probe on the incident on February 4.

Will the truth come out at all? – with reports from Glenda M. Gloria/Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.