SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

Illustrations by Geloy Concepcion Design by ANALETTE ABESAMIS and DOMINIC TUAZON

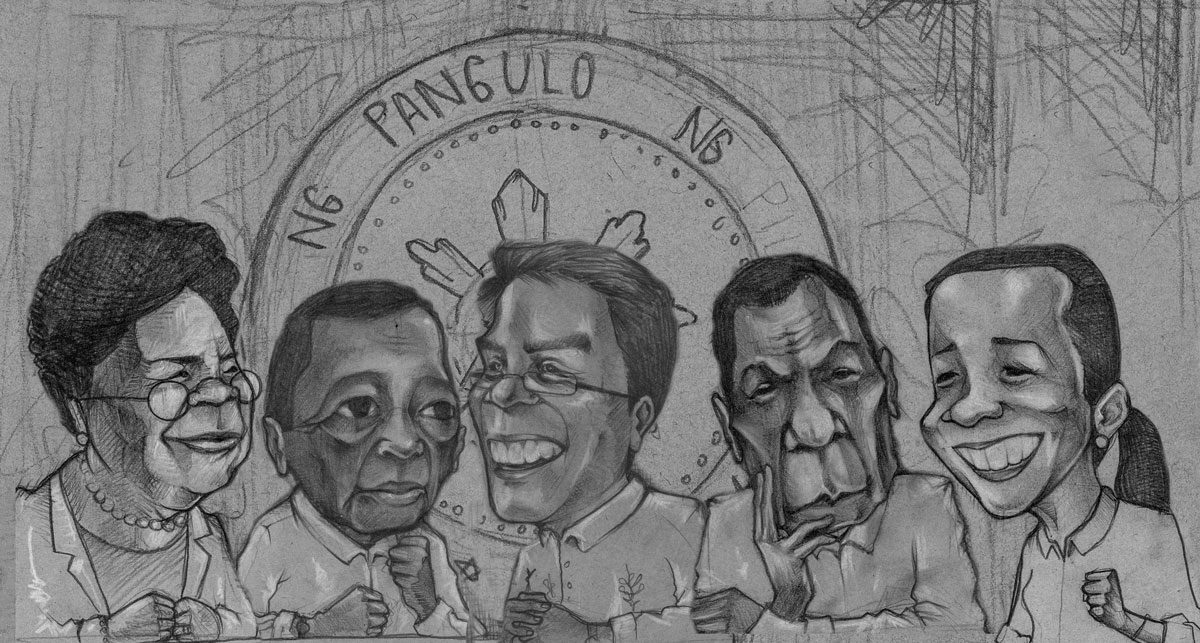

Our series of presidential profiles, The Imagined President, began with The Idealized candidate, introducing the candidates as imagined by themselves and their supporters. (READ: Mar of the People) The second installment, The Demonized, examined the candidates as imagined by their critics. (READ: Heir to the Kingdom). In this final installation, we give you The Candidate, a synthesis of both narratives as seen through the lens of journalism and sociology.

We invite conversation and discussion, and promise, if nothing else, to tell you a story.

The chandeliers are lit at midmorning. They hang low from the ceilings, burning white in photos and flaring at odd angles. The painted walls might have been plaster, might have been wood. Women with dyed and coiffed hair tap their knees with folded fans. The public relations people, the executive assistants, the retired politicians, are already making the rounds, slapping backs and leaning over to buss cheeks, dressed in the collared yellow shirts with the black stripe on the shoulder. The talk is of golf and survey numbers.

It might all have been elegant, once upon a time. Certainly not now, with the chipping paint and the parquet floors gone dull with age. There is a comforting continuity here, the sense of being slightly out of step with time – like walking into the musty damp of a school library that still keeps a card catalog. This is the hall where Corazon Aquino in her yellow puffed sleeves was inaugurated as president of the republic, and this is where Mar Roxas will stand and hope for his.

The front row is half empty when the video plays. The photos flash by. There is Mar Roxas, in cap and gown. There is his father the president, and then Ninoy Aquino, both rendered in faded sepia. There is Mar Roxas stepping down to support the presidency of Benigno Aquino III. Look at Roxas standing in the aftermath of disaster, and at the center of the Senate floor, and at the foot of a coffin draped in the Philippine flag. Watch him, in a factory hunched beside a machinist, in a market carrying a plucked chicken, on a stage receiving an award, out in the provinces, grinning with his arms around a clutch of elderly.

This is the Mar Roxas as the Liberal Party imagines him – man of the people, adored and acknowledged, the unifying leader destined for the presidency. It is a pretense as evident as the slipcovers hanging loose over the monoblock chairs – the plastic legs poke out, the shape of it the same.

The old world is dead. The politics of 2016 is no longer decided in golf courses or the polite halls of Club Filipino. They surge wild in the streets, in the roiling, seething crowd punching fists under the Davao sky.

Heir to the kingdom

Mar Roxas was not the son born to the presidency. It was his younger brother, Dinggoy, who was “meant to be our generation’s contribution to the principle we inherited from our grandfather: “Country before self.” We are told it was Dinggoy who had a genius for people, and was the sort of young man who would stop for a car wreck to help the dazed occupants home. He won the congressional seat of the Roxas stronghold Capiz at 27. His brother Mar worked as investment banker in New York.

Dinggoy died a year after his second term. He was 32. That loss thrust his reluctant older brother into the political field.

Mar may have been the Roxas family’s second choice, but we are told theirs is a duty that demands leadership. Roxas’ uncle, political analyst Tony Gatmaitan, puts it franker terms – “[Mar] was forced into it.”

There was a time when pundits were sympathetic with Mar Roxas. After he lost the vice presidency in 2010, he could have cruised to Malacañang after overhauling airports and trains as secretary of transportation and communications. He could have won public support by revamping the police, facing down crime, and dealing with the twin crises of conflict and disaster. Unlike Jesse Robredo, the much-loved Naga mayor forced to share power with Aquino cronies, Roxas began his term as chief of the interior with the full support of Benigno Aquino III. He had every opportunity to prove his effectiveness at the helm of two of the most vital government posts. He could have set the stage for an easy win in 2016.

Had Mar Roxas been a competent executive, had he understood that his presence in a crisis – “We were in Zamboanga from the very first day” – is not a virtue without actual results, and had he been able to see grievances against the Aquino administration as real instead of the jealous malice of critics, the presidency could have been his. He failed, and failed in full view of a desperate public.

It would be unfair to say that his charmed upbringing disqualifies him from a life of public service. It is not being a Roxas that makes him unfit, it is the belief that being a Roxas grants the presidency to a man so obviously unsuited for the role.

Mar of the people

Roxas claims to have a pro-poor track record. He passed the Cheaper Medicines Act. He successfully lobbied for the Special Economic Zone Act that galvanized the BPO industry. His pet programs required years of research and study: the lifting of European Union ban on Filipino airlines and the rollout of a data-driven crime prevention effort.

A vote for Mar Roxas acknowledges the slow character of nation building – a project that requires patience instead of quick-fix solutions. Inclusive growth takes time. Eliminating corruption takes time. The impact of hard work may not be immediately apparent, but the statistics of crime and economic growth indicate we are headed in the right direction. Roxas promises more of the same.

Except that the world we live in is one where we cannot afford to wait. Ours is a country where the sky falls with clockwork regularity. Disaster is the new normal. Every day is a crisis. He may excel in the minutiae of the law, but the next president of the Philippines does not have the luxury of endless meetings and a selection of excuses.

Today, the images trump the rain of yellow confetti: Sta Catalina burning to the ground, the bodies bobbing in the shallows on the edge of Leyte Bay, the sweaty heat of a stalled train at the Shaw Boulevard station.

Everywhere is the face of Mar Roxas, saying this is the best that can be done.

Wildest dreams

One week before the elections, Roxas has yet to become a front runner in any credible presidential poll. If the 2016 election is a referendum on the quality of service Roxas has delivered to the country, then it is telling that more would rather pin their hopes on a political neophyte with a dream, or a vice president accused of corruption, or the mayor who equates enforcement with death.

In spite of this, he remains what the Liberal Party touts “the only decent choice.”

“Why must we allow ourselves to be attracted to maybe,” said Aquino, “when we can be certain? We will go with whom we can be certain will continue the Straight Path. And I believe that person is none other than Mar Roxas.”

Yet Aquino’s faith in his loyal lieutenant is not as robust as the Liberal Party would have the people believe. Aquino withheld the nomination while speculation spread, meeting with Senator Grace Poe before he gave his blessing to Mar Roxas. In the tearful aftermath of the misencounter that killed more than 60 in Mamasapano and cut short the flagship legislation for the creation of the Bangsamoro state, it was Roxas, head of the interior department, under whom the police reported, who knew nothing about the operation. His own President saw fit to circumvent the chain of command and confide in a suspended police chief instead of his right hand man.

Roxas’ promise of continuity does not offer relief. His will be an administration where the economic projections will remain positive just as daily lives are nasty, brutish and short. He can talk big with the suited gentlemen of the Makati Business Club, but he has very little to say to the jobless and hungry who spoke on national television at the last presidential debate. There was Jun, whose father died in two days because the hospital was too far, and Perla who loses six hours a day to traffic, and Carlos who can’t get a steady job no matter how hard he tries, and Cristi, who is sick without insurance overseas and just wants to go home to see her babies grow up.

Roxas spoke about health being wealth and programs that exist, about loopholes in the law and rising employment rates. He talked at them – but not to them.

What some call Roxas “failure to connect” is not just a minor issue of charisma. It is an issue of recognition – the President of the nation should be able to give voice to the most desperate people he represents, and the first step to that representation is having the capacity to listen and to empathize.

Roxas’ reaction, as is Aquino’s, is a defense of their Daang Matuwid. Those who come to lay grievances at their feet are left frustrated, helpless and, as the nation has seen in the past months, vulnerable to a demagogue who promises to make real our wildest dreams.

The yellow brick road

In spite of this, Roxas remains what the Liberal Party touts “the only decent choice.” The choice is black and white. The binaries have been laid out: the decent versus the barbarians, the decent versus the immoral, the decent versus those who would push the country down to hell on a handcart. This is the dangerous territory of exclusionary elitism, of claiming moral high ground without actually listening to why voters have become so desperate to place their bets on other candidates.

And yet is a young teacher in the conflict zones of Lanao del Sur to be blamed for choosing the Mindanao-born Rodrigo Duterte? Can a taxi driver be called a barbarian for wanting a president who can put a stop to corrupt traffic cops? Is it not reasonable for a starving farmer to protest against the yellow army when the drought kills his bananas and the governor says he doesn’t deserve help?

In the last months of the campaign, the mayor of Davao has cast himself as the antithesis of everything Mar Roxas has become in the public imagination – bumbling and slow, charmless and dull, reduced to a whipping boy by the howling denizens of social media. Roxas is the man with the winding sentences and the semi-colons. Duterte is the gunslinging 70-year-old with 140-character smackdowns.

Roxas greets the veterans of Zamboanga siege a happy anniversary, and forgets the displaced victims who died in the heat of temporary shanties. He sees the dead farmers who marched for rice in Kidapawan, and asks who funded the protests.

“If we compare choosing a president to choosing who will drive our children every day,” Roxas asked, “whom will we choose? To whom will we trust the safety of our children?”

Here is a candidate so out of touch with his own constituency that he is unable to grasp that the majority of parents in the Philippines do not own cars, cannot afford private school buses, and consider themselves lucky when their children can go to school at all, even when they are forced to wade barefoot through rivers or risk getting run over by trucks thundering down the highways.

His name is Manuel Araneta Roxas II. Son of a senator, grandson to a president, anointed heir of two dynasties, and the last living hope of a dream that was born in the sugar plantations of Negros. He is the second choice, but we are told second is the best we deserve. Under his reign, the chandeliers will burn white in a city where the sky glows ultramarine. – Rappler.com

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

Join Rappler+ Donate Donate UPGRADE TO RAPPLER+ TO COMMENT JOIN RAPPLER+ TO COMMENT

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.