SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – The Department of Justice (DOJ) will have a very precarious role in the contested anti-terror bill once it is passed into law.

A key feature of the bill is the Secretary of Justice’s membership in the powerful anti-terror council (ATC) while his prosecutors will have the task to dismiss or approve the council’s cases.

Under Section 45 of the anti-terror bill, Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra will be among the 9 members of the council. Guevarra is the vice chairperson of the council in the current Human Security Act.

He will be relegated to the role of member in the bill’s ATC. Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea will remain the chairperson, with National Security Adviser Hermogenes Esperon Jr as the vice chair.

Section 29 of the bill authorizes the anti-terror council to order in writing law enforcement agents to arrest suspected terrorists. (READ: EXPLAINER: Comparing dangers in old law and anti-terror bill)

In the same section, law enforcement, by authority of the council, may keep the suspect in custody for as long as 24 days. This is an extension from the original 3 days, a provision that the Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP) said was unconstitutional.

When law enforcement finally brings in the suspects for prosecution, the prosecutor would decide whether there is probable cause to indict them for terrorism, or clear them

There is a seeming conflict in this situation because the National Prosecution Service (NPS) is under the DOJ, whose secretary is in same council.

“If that person will be the subject of the authority of the anti terror council to be subject of surveillance, to be detained, then our boss, the secretary of justice, has already spoken. If as a prosecutor, the case will be brought to me, what will I say? Will i say that there is no case knowing what my boss has already said?” former DOJ undersecretary Leah Tanodra-Armamento said on Rappler Talk.

Armamento served as DOJ Undersecretary from 2010 to 2015, was a longtime prosecutor before that, and is now a commissioner at the Commission on Human Rights (CHR).

“This law will make the National Prosecution Service as a stamping pad,” said Armamento.

Asked to respond to this, Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra said: “The Secretary of Justice has no participation in the investigative process, but exercises the power of review.”

Asked to clarify whether the justice secretary will not have a hand at all in the council’s power to authorize arrests under Section 29, Guevarra said “we cannot comment on Section 29 unless we have reviewed the bill in its entirety.” (READ: A tale of two justice secretaries: The De Lima-Guevarra balance)

Independence of the NPS

“Granting ang tapang tapang ko, napaka independent ko na tao (granting I am a brave soul, I am so independent), I will say I will dismiss the case. You can always appeal to the Secretary of Justice who is a member of the anti terrorism council and he can always reverse me, and file a case the way they have decided at the anti-terrorism council. This is not a good venue for you to get remedy from the NPS,” said Armamento.

In the DOJ, the first step to appeal a prosecutor’s resolution is to file a motion for reconsideration before the NPS, after which you can appeal a petition for review to the justice secretary.

Guevarra insists the NPS is independent.

“The justice secretary’s role as a member of the anti-terrorism council which deals with policies and his role as reviewing authority in actual cases investigated by the National Prosecution Service are separable and can be performed independently of each other,” said Guevarra.

“I don’t want to indict my fellow prosecutors, we are trying our best to be independent … .but reality check, we have a boss, it’s your personal conviction vs your personal welfare,” said Armamento.

Burden of proof shifts

Under Section 4 of the bill, where terrorism is defined, there is an exception – that “terrorism as defined in this Section shall not include advocacy, protest, dissent, stoppage of work, industrial or mass action, and other similar exercises of civil and political rights.”

The bill’s sponsors, and even the DOJ, use this to defend the bill.

However, the provision in its entirety has a catch. There is an exception to the exception, meaning dissent is not terrorism if it’s not “intended to cause death or serious physical harm to person, to endanger a person’s life, or to create a serious risk to public safety.”

For lawyers, the way that provision was worded means dissent was equated to terrorism, except if there’s no intent.

And who has the burden to prove there was no intent?

“Me as the respondent. Yes, [the burden of proof] has shifted,” said Armamento.

“All that the State, through the DOJ, needs to do is to allege the exception to the proviso, i.e that the intent is to cause death, harm, or risk,” said former Supreme Court spokesperson Ted Te.

Armamento said the exception is not a safeguard at all.

“It’s like consuelo de bobo (fool’s gift), so you can say you have your day in court but after all the damage has been done, after you’ve detained me and made me suffer for offenses that I may not have committed but only by your mere suspicion, so it’s dangerous,” said Armamento.

DOJ review

The DOJ refuses to comment on specific questions about the provisions saying it can’t do so until its review on the bill’s constitutionality is done.

Because the anti-terror bill is an enrolled bill – meaning it did not pass through further scrutiny at the bicameral committee because both houses of Congress passed the same version – the bill will be sent to concerned agencies for comments.

Comments would be consolidated by Medialdea, who would submit his recommendation to President Rodrigo Duterte.

If the law is passed, it is the DOJ which will have to write the Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR).

“The DOJ will endeavor to define more clearly in the IRR the parameters within which the law will be implemented and enforced, in order to erase any latitude for misapplication or abuse,” said Guevarra.

In 2017, under Vitaliano Aguirre II, the DOJ used the Human Security Act to proscribe 649 people as terrorists, including prominent activists and a United Nations Special Rapporteur.

Guevarra would eventually admit that the list of 649 people was not verified, and the DOJ under him trimmed the list to only 8.

In the 2020 anti-terror bill, suspects can be preliminarily declared as terrorists without a full trial.

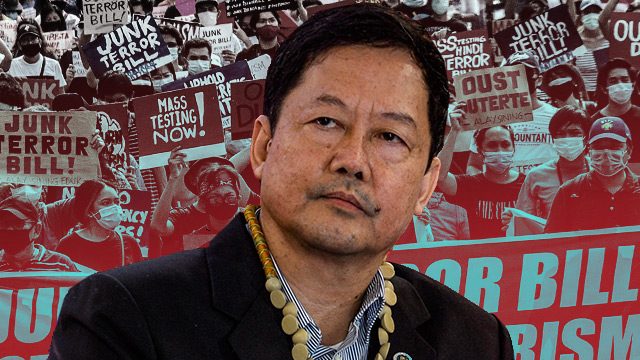

Human rights lawyers are calling on Guevarra to side with them on this bill. National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL) president Olalia appealed to Guevarra saying “history, your peers, and your family will judge you for what you will do for the bigger picture and greater future for the vast many.”

Guevarra said he trusts that Duterte will have a “good grasp of any legal or constitutional issues involved.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.