SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This is what the Supreme Court (SC) has recently done – create a rule requiring policemen to wear body cameras, review rules on extraordinary writs, and revive a human rights committee.

The human rights committee is currently evaluating attacks against lawyers, along with red-tagging of activists.

Advocacy groups would hail all those moves as responsive, a Supreme Court attuned to the problems on the ground at a time where lawyers claim the rule of law is under attack.

But is there such a thing as being too proactive?

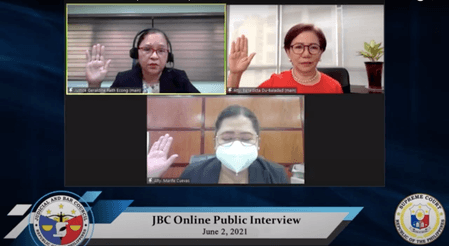

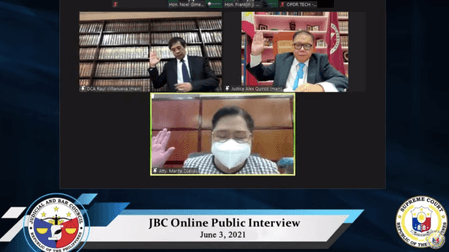

That was the discussion of the Judicial and Bar Council (JBC) when they interviewed applicants for a spot in the High Court, driven mainly by the JBC’s Noel Tijam, a retired SC justice.

They were interviewing for the slot left by retired justice Edgardo delos Santos, one of the two vacancies to be filled by appointees of President Rodrigo Duterte.

Human rights committee

“What significant purpose will a human rights committee serve considering that we have a Commission on Human Rights?” asked Tijam during the interview conducted on Wednesday, August 11, but which was uploaded by the JBC only on Friday, August 13.

Court of Appeals (CA) Associate Justice Apolinario Bruselas, an applicant, said: “I think this is a matter of conserving the resources of the Supreme Court, you cannot be having committees left and right, and disbursing resources, assets, brainpower into these committees.”

Bruselas said there was “a more efficient and less cumbersome” way to monitor human rights abuses.

This earned a sharp response from Chief Justice Alexander Gesmundo who asked Bruselas: “Are you saying that the human rights committee is a waste of resources? Is human rights not a priority, is that what you’re telling me?”

“Committees involve committee work, if there is a way of addressing the problem without creating a committee…that’s just my opinion,” said Bruselas.

Sandiganbayan Presiding Justice Amparo Cabotaje Tang, also an applicant, was the head of this committee under former chief justice Maria Lourdes Sereno, who was ousted in May 2018.

Tang revealed during the interview that her committee had submitted a report to the Supreme Court on whether the writ of amparo was still effective in protecting the rights and liberty of those who want to avail of it.

Activists have long complained of a weakened amparo. Bacolod-based activist Zara Alvarez requested for an amparo but it was denied by the CA. They appealed to the SC but Alvarez was shot and killed in August 2020 before the SC could act.

“We submitted a report to then-chief justice Sereno, but nothing came out of that. I wrote a letter, I think, to Acting Chief Justice (Antonio) Carpio but again there was no action on that request of mine,” said Tang.

What’s wrong with being proactive?

The Supreme Court has extraordinary rule-making power, one of the few high courts in the world to possess it. Rules have evolved to make justice more efficient. Former chief justice Diosdado Peralta boasted of approved 18 procedural rules before he left.

CA Justice Ramon Cruz, also an applicant, said the many rules like continuous trial – which envisions a case lasting only six months – would give the judges too many jobs, and make them too proactive.

“Is there something wrong when you make judges proactive rather than rely on the parties’ submission?” asked Gesmundo.

“I was thinking of a situation where judges are now pressured because of so many rules requiring them to act on a particular case or incidents motu proprio (on its own),” said Cruz.

“What’s wrong with that?” Gesmundo pressed.

“In the traditional sense, judges would wait for pleadings filed by the parties,” said Cruz.

Judicial activism

The JBC also discussed at length the principle of judicial activism, where the Court is more liberal in its decisions or actions, at the risk of being accused of encroaching on the powers of the two other co-equal branches.

The creation of the writs of amparo and habeas data to respond to the human rights abuses during the time of former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo is seen by many as a display of judicial activism.

What action is considered judicial activism, and whether it’s wrong or right, depends on who is asked.

Finance Undersecretary Antonette Tionko, another applicant, said the extraordinary writs are not a case of judicial activism, and that she doesn’t agree with judicial activism.

“I think it’s when a judge or a justice actually propounds his own ideas, furthers his own ideas in his decisions, I don’t agree with it,” said Tionko.

Tang said the Supreme Court also demonstrated judicial activism when it issued the 2008 landmark decision granting a writ of continuing mandamus for Manila Bay, compelling government agencies to rehabilitate it over a period of time, which continues to this day.

“I think that’s part of judicial activism, because here, the Court for the first time, exercised judicial supervision over all these executive agencies which were directed to constantly clean up Manila Bay,” said Tang.

Was the Supreme Court’s grant of humanitarian bail to plunder defendant Juan Ponce Enrile judicial activism, asked JBC’s Jose Mendoza, also a retired SC justice.

While Tang said she doesn’t believe Enrile’s bail was a case of judicial activism, she pointed out that the Supreme Court used humanitarian grounds as basis for granting him bail even though the former senator did not raise it before the Sandiganbayan, the original court trying the plunder case.

All of these judicial principles are complicated.

Tionko believes the perceived public mistrust in the judiciary is largely due to most people being unaware of what the Court does, or what it’s supposed to do.

But even the Court’s public engagement is up for debate, with some choosing the so-called dignity of silence.

Tijam asked: Should the Court even care, and ultimately, “are people interested about the workings of the Court unless they are parties?” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.