SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – In the old office of one of the country’s biggest law firms, a picture of two men in their target-shooting gear hung on display. One of them was a co-founder of the firm, whose most prominent client was Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. The other was his shooting buddy and schoolmate, whose boss was also Mrs Arroyo.

When the law firm left its old office in Makati in 2010, it left the picture behind. Suffice it to say that the photo could not be seen in the new office anymore.

The CVC law firm, after all, was all set to turn a new page after breaking ties with Mrs Arroyo and her husband, whose family owns the Makati building where the law firm held office for over two decades.

The firm’s co-founder in that photo is Antonio Carpio, now Supreme Court associate justice. The other man in that discarded picture is Carpio’s colleague — and superior — in the bench: Chief Justice Renato Corona.

Glory days

CVC law was founded in 1980 by Carpio, Arthur Villaraza and Avelino Cruz Jr.

Because of its clout in the Ramos and Arroyo years (Carpio had served as presidential legal counsel of former President Fidel Ramos), the law office was eventually referred to as “The Firm,” a once-derisive tag connoting cold-bloodedness but which it now proudly displays in its spanking new office in Global City, Taguig.

When Mrs Arroyo replaced President Joseph Estrada in January 2001, following a military-backed civilian revolt, she put some of the law firm’s top executives in key positions of power.

Shortly after becoming president, Mrs Arroyo named Cruz as chief presidential legal counsel and, 3 years later, defense secretary.

Simeon Marcelo, another senior partner in The Firm, was appointed Solicitor General in January 2001 and then Ombudsman in 2002.

Carpio, who left the law office in 2001, was appointed SC justice on the same year.

Lawyers close to both Carpio and Corona say their friendship began to hurt at this point, since Corona had always wanted to be in the Supreme Court but Carpio got to the High Tribunal ahead of him.

Corona had reasons to expect an SC appointment. Though not connected with The Firm, he supported Arroyo during the crucial months that led to Estrada’s ouster.

And Corona proved his loyalty to the end. In contrast, when the CVC law firm left LTA in November 2010, its ties with Arroyo had long been severed.

Today, Corona is openly accusing Carpio and The Firm of being behind a powerful lobby to remove him as chief justice.

Now the subject of an impeachment trial, Corona asked Carpio to inhibit from cases concerning the ongoing impeachment proceedings, saying that the latter “begrudged” him for his appointment as Chief Justice in May 2010.

Corona himself declared that “the enmity and rivalry” between them is “common knowledge.”

Allies, friends

This was not the case 11 years ago.

What was common knowledge then was their friendship and shared interests.

Both worked for two presidents: Ramos and Arroyo. On a personal level, Carpio stood as godfather to one of Corona’s children, and vice versa.

Both also played pertinent roles in the rise of Arroyo to the presidency.

At the height of Edsa 2, on Jan 20, 2001, when thousands of activists had gathered on Edsa to demand the resignation of Estrada, Mrs Arroyo, who was then his vice president, wrote a letter to the Supreme Court to inform the justices that she was ready to take over the presidency. The defense and military establishments by then had thrown their support behind her.

In her book “Shadow of Doubt: Probing the Supreme Court,” journalist Marites Dañguilan-Vitug, Rappler’s editor-at-large, wrote that it was Carpio who drafted Arroyo’s letter to the SC. (However, a source privy to the events leading to Estrada’s ouster said Carpio merely “reviewed” it.)

The letter provided the impetus for then Chief Justice Hilario Davide to later swear in Arroyo as President.

During this period, Corona was part of Arroyo’s transition team, along with Renato de Villa, Alberto Romulo and Hernando Perez (all of whom would later be named Cabinet Secretaries). The team was in the thick of negotiations with Estrada’s own men before Arroyo was sworn in as President.

Inquirer columnist Belinda Olivares-Cunanan had written that Estrada specified conditions for his abandonment of the post, which included immunity from lawsuits. Cunanan wrote that Corona blew his top when Estrada’s supposed resignation letter — drafted by Estrada’s chief of presidential management staff, Macel Fernandez — did not include the word “resignation.”

In the end, Estrada left the Palace, Arroyo was declared President, and both Carpio and Corona basked in her victory.

Carpio and Mrs Arroyo had worked together before this.

He was, in fact, one of those who pushed Arroyo to run for president as early as 1998, the presidential race that Estrada won. “Carpio suggested to GMA that she run for president,” a source who worked with the two said. Due to lack of funds, however, Arroyo decided to run for vice president instead. And she won.

Arroyo got to know Carpio and Corona through one man: Fidel Valdez Ramos.

And it was Carpio who made possible the entry of Corona into the Ramos camp.

Two Ramos government sources told Rappler that it was Carpio who helped Corona get the post of assistant executive secretary for legal affairs under the Ramos administration.

A former senior Palace official under the Ramos government disclosed that in 1992, shortly after Ramos won, Corona wrote Carpio, who was then chief presidential counsel, about his wish to work in government. (Corona previously worked as legal counsel of the accounting firm Sycip, Gorres & Velayo.)

They knew each other, after all.

Carpio and Corona are both Ateneans. Carpio completed his elementary and secondary studies in Ateneo de Davao, while Corona studied in Ateneo de Manila. Their paths crossed when Carpio studied economics in Ateneo de Manila while Corona enrolled in the general studies course.

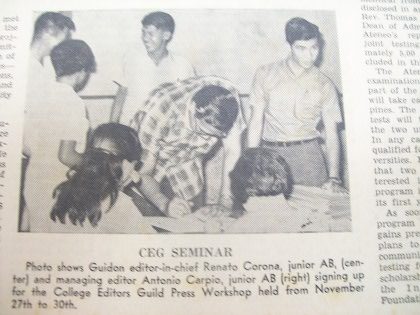

In college, Corona served as editor in chief of The Guidon, the campus newspaper. Carpio succeeded him.

Linggoy Alcuaz, a batchmate, wrote in his column in globalbalita.com that Corona ran for student council president in his junior year in college, but lost to Edgar Jopson, a prominent activist who was later slain by military troops.

Corona and Carpio finished college in 1970. Corona however took up law in Ateneo, while Carpio finished his law degree at the University of the Philippines.

Corona’s luck

When Arroyo became the vice president in 1998, Corona was considered for the post of chief of staff. A former government official said that Carpio, who was then a close adviser of Mrs Arroyo, again backed Corona’s appointment.

What bolstered Corona’s chances was that Mrs Arroyo’s husband Mike also knew him. Both graduated from Ateneo law school (Arroyo in 1972, Corona in 1974). In 1998, Corona became Mrs Arroyo’s chief of staff, after Raul Palabrica and Willie Villarama.

In an interview with The Guidon, Corona said that he didn’t want the post and that of a presidential spokesman (he became one when Arroyo rose to the presidency in 2001) because these appointments can be “political.”

The following years would show how Corona had adapted to the ways of politics.

The race for chief justice

As early as 1998, when President Ramos was about to end his 6-year term, Corona wanted to join the Supreme Court. Ramos himself pushed for his appointment, but then Chief Justice Andres Narvasa stood his ground, saying that the Judicial and Bar Council — which vets aspirants for the judiciary — could not finalize a short list for justices because of the election appointment ban.

The appointment ban barred presidents from making any appointments two months before the elections and until his or her term ends on June 30.

In 2001, when Arroyo became president, the opportunity for Corona to become SC justice surfaced again.

This time, however, insiders in the SC reportedly said that Corona was too young to be named justice. A source told Rappler that some of the justices felt then that Arroyo’s first appointee in the SC should be a “[legal] heavyweight.”

Besides, there was a strong lobby for Carpio.

While Arroyo initially considered Carpio for the post of Ombudsman, his colleagues in The Firm reportedly advised him to take an SC seat, given his seniority and the opportunities that the post offered.

Carpio was appointed to the Tribunal in October 2001. Corona followed a year later, in 2002.

The Supreme Court, to put it bluntly, broke their friendship.

They clashed over principles, politics, people — in particular Mrs Arroyo.

On sensitive issues, they took opposite sides. Examples of these are:

- The SC, in a vote of 8-7, declared the Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain (MOA-AD) between the government and Moro Islamic Liberation Front unconstitutional. Corona dissented, saying it was moot and academic because the MOA-AD was not signed; Carpio sided with the majority.

- The SC, in a vote of 9-4, ruled that the RP-US Visiting Forces Agreement did not violate the Constitution, but said that the transfer of rape convict Lance Cpl. Daniel Smith to the US Embassy was not in accordance with the agreement. Corona voted with the majority; Carpio dissented.

- The Court struck down the People’s Initiative case which sought to revise the Constitution and change the current presidential form of government from presidential to parliamentary. Carpio wrote the decision; Corona dissented.

- The SC declared the joint venture agreement (JVA) signed by the Public Estates Authority and Amari company null and void for violating Section 3, Article XII of the 1987 Constitution, which prohibits private corporations from acquiring any kind of alienable land of public domain. The High Court also stopped the two parties from implementing the JVA. Corona was with the majority initially, but when the SC denied with finality the motions for reconsideration filed by Amari Coastal Bay Development Corporation, he reversed himself and dissented. Carpio wrote the majority opinion.

- The SC upheld executive privilege, which then Socio-economic Planning Secretary Romulo Neri invoked when asked at a Senate inquiry about Mrs Arroyo’s instructions to him on the aborted US$329-million NBN-ZTE deal. Corona sided with the majority; Carpio dissented.

Corona and Carpio were nominated for the post of chief justice in time for the May 2010 retirement of then Chief Justice Reynato Puno. Carpio declined his nomination, claiming the appointment was covered by an election ban. Corona accepted his, and was eventually named to the post. Critics have called his selection a “midnight appointment.”

Politics is personal

The SC also issued a status quo ante order in favor of Arroyo’s ally Merceditas Gutierrez, the Ombudsman who was about to be impeached by the House of Representatives. The order stopped the House committee on justice from proceeding with the impeachment process.

The SC eventually lifted this order, paving the way for Gutierrez’s impeachment (she quit before the Senate could try her). Carpio agreed with that decision, while Corona dissented.

The straw that broke the camel’s back for Aquino, however, was the issuance of a temporary restraining order stopping the Department of Justice (DOJ) from implementing its hold departure order against the Arroyo couple. The DOJ had barred the two from leaving the country in 2011 because they were facing a preliminary investigation for alleged cheating in the 2007 senatorial elections.

Aquino went on the offensive and criticized Corona as Arroyo’s lackey. In December 2011, Corona was impeached by the House.

Corona’s impeachment brought to the fore his damaged relationship with Carpio. In a scathing speech before SC employees in January, Corona said one of those who lobbied for his impeachment is an associate justice who has been itching to get the position from him.

“It was a tragedy. Ambition got in the way,” said the lawyer who saw the old photo of the two former buddies displayed in the old CVC office. – Rappler.com

Click on the links below for more stories of Corona’s relationships with the personalities in the trial.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.