SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

If petitioners had to battle the often-used justification of national security, government lawyers were finally compelled to defend the anti-terror law’s biggest constitutional gaps, courtesy of the junior justices of the Supreme Court who took the first turns of interpellations on Tuesday, May 4.

Associate Justice Rosmari Carandang opened the government interpellation last week, by tradition as she is the member-in-charge, but during Day 6 on Tuesday, the Supreme Court reversed the sequence so the most junior began first.

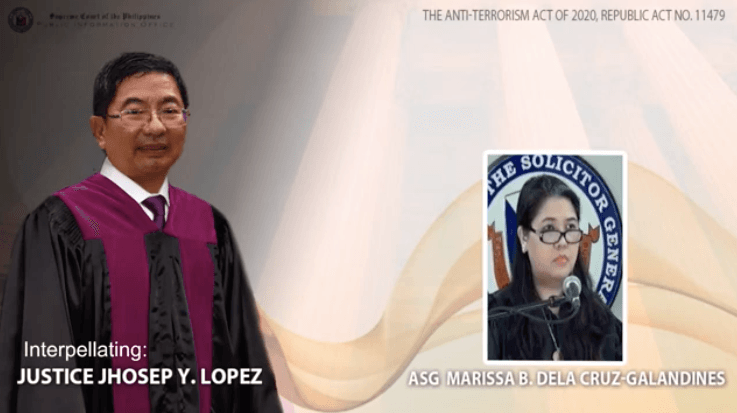

Justice Jhosep Lopez, who asked petitioners two months ago whether “right to privacy must give way in order to curb threats of terrorism,” came out swinging in asking solicitors general about the loopholes of the law’s most contentious provisions.

For example, Jhosep Lopez said that under the 1987 Constitution, or Article 7, Section 18, the maximum period to detain a person without a charge in court is only 3 days, and that’s even under a state of martial law. Martial law is declared when there’s a state of rebellion or invasion.

Anti-terror law allows a 24-day detention for a person arrested without warrant and without a charge.

“What makes you think under ordinary times like what we are having now [that] you can detain a person to as many as 24 days when the Constitution limits it to 3 days only at maximum?” the justice said.

Assistant Solicitor General Marissa dela Cruz-Galandines said that “terrorism is different from just an ordinary crime.”

So you want to change the Constitution, the justice prodded.

“Not that we have to change the Constitution, your honor, but it’s just that Congress in its wisdom provided for a different period in cases of terrorism. Terrorism must evolve from 1987 to the present,” said Galandines.

The 24-day detention is found under Section 29 – a provision that largely took a beating during Day 6.

Justice Samuel Gaerlan pointed out that the implementing rules and regulations (IRR) suddenly clarified that suspects may be arrested without warrant pursuant to the existing rules on warrantless arrest.

The wording of the law did not specify that, which built the petitioners’ cases that Section 29 empowered an executive body like the anti-terror council to arbitrarily order arrests without a judicial warrant.

“Isn’t the IRR’s inclusion of the grounds of the rules of court for warrantless arrest, in Rule 9.2, an admission that Section 29 is unconstitutional as written in the law?” Gaerlan said.

When Galandines insisted that the 24-day detention power “follows a valid warrantless arrest,” Gaerlan said, “Are you not asking the court to unreasonably stretch the interpretation of the law in order for it to be valid?”

Like a light conviction

Justice Edgardo delos Santos pointed out that 24 days is as long as the jail time imposed on someone convicted for a light offense, but in this case, for someone not even charged yet in court.

“Will this not be violative of the constitutional prohibition that no person shall be held to answer for a criminal offense without due process of law, because effectively a person detained would be deprived of liberty even without a judgment by court of law finding him guilty beyond reasonable doubt?” said Delos Santos.

“We submit that detention under Section 29 is class of its own,” said Galandines.

In all of this grilling, Galandines only had his fellow assistant solicitor general, Raymund Rigodon, to help her out. Solicitor General Jose Calida, present on the Zoom, did not step in. The justices didn’t compel him either.

Delos Santos also asked: if the government so claims that its arrests will still be dependent on the standards of probable cause, then why does it need 24 days to detain a suspect?

This was pointed out in several petitions: if the government were to follow a reasonable standard, can’t it build up a case strong enough to convince a judge to issue an arrest warrant?

“Additional days of detention is justified in this crime of terrorism so that we could prevent further commission of the same acts,” said Galandines.

Designation

Another contentious provision is Section 25, which authorizes the anti-terror council to designate on its own, through secret hearings, persons and groups as terrorists. The government claims it’s only for the purposes of freezing their assets and not to arrest or detain them.

It’s a distinct power from proscription, which is a judicial process and needs to go through court trial.

“Why do you have to make a distinction when you can go immediately to the court where due process is properly observed and ask for a proscription?” said Jhosep Lopez.

“In proscription, the individuals are not yet known,” said Galandines, telling the justice it’s not just her interpretation “but the correct interpretation.”

Galandines brought up the fact that the IRR added a process of delisting so that designated people have a remedy. Delisting is not found in the law itself.

“Can you implement something which cannot be found in the law? How can it be valid when there is no law itself?” asked Jhosep Lopez.

“We submit that the law must be read in whole,” said Galandines.

‘Small price to pay’

Under Section 34, suspects charged with the non-bailable crimes of the law who win a petition for bail can still be put on house arrest with no access to any means of communication.

Delos Santos asked: does that not violate the right to bail?

Galandines answered, “It’s a minor inconvenience, a small price to pay compared to the issue of national security.”

Justices Ricardo Rosario and Mario Lopez also asked questions on Tuesday, before they had to adjourn at 5:30 pm.

Rosario said that because the law “merely requires” law enforcement to notify a judge in writing that a suspect has been arrested, “it appears that the law basically grants unrestricted authority to the law enforcement.”

Galandines cited the safeguards, such as a 10-year imprisonment for law enforcement who fails to comply with such requirements.

In earlier hearings, justices asked: can’t a detained suspect file a petition for the protective writ of habeas corpus so he or she can be freed?

Rigodon said on Tuesday it’s not possible.

“If there’s an anti-terror council authorization for an extended detention, habeas corpus will not lie, because a habeas corpus inquires into the validity of detention, and since such definition is authorized by Congress itself, then the detention is valid,” said Rigodon. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.