SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

BACOLOD CITY – Fr. Armand Onion was a young priest in the mid-80s when then-bishop Antonio Y. Fortich assigned him to the Bacolod Diocese’s social action desk.

Onion was on intimate terms with poverty, having served in parishes of fisherfolk and sugar workers, where Fortich had long established supplemental feeding for children.

But nothing prepared the clergy for 1985, when it became clear that the diocese’s soup kitchens could no longer keep pace with mass hunger in Negros Occidental, the country’s sugar bowl.

September 1985 in Negros was the apex of corruption and brutality under the late dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos.

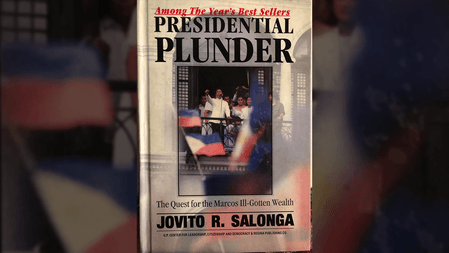

Trading monopolies headed by Marcos cronies had ravaged the sprawling haciendas of the country’s sugar bowl. Sugar planter Fred Hilado told Rappler the industry lost around $1.15 billion from 1975 to 1984 to plunder under the Philippine Sugar Commission (Philsucom) and the National Sugar Trading Corporation (NASUTRA).

Both agencies, and the Republic Planters Bank, which handled trading funds, were headed by the same cabal led by Roberto Benedicto, Jose A. Unson, Jaime C. Dacanay, and Fred Elizalde.

As sugar producers faced bankruptcy, most abandoned their estates, leaving 190,000 sugar workers with around a million dependents to fend for themselves.

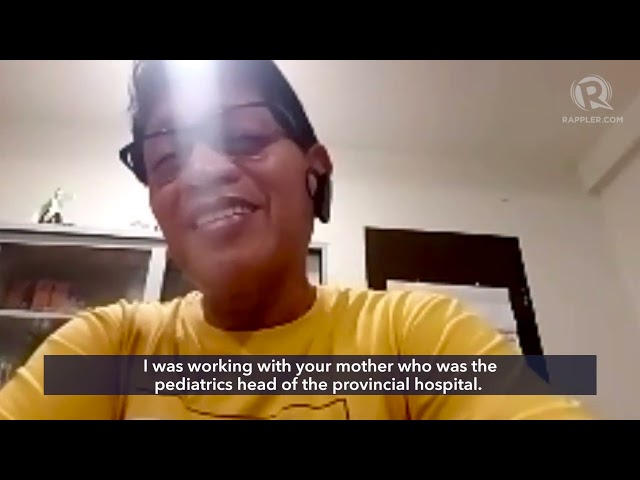

Onion ministered to grief stricken parents of children dying in the pediatric ward of the provincial hospital just a stone’s throw away from the Cathedral.

They were from families that had fled the sugar estates – home to generations of restive sakada or hacienda field hands – for non-existent jobs in the capital of a monocrop province.

Benedicto, meanwhile, had assets of around $800 million in 1983, according to Ricardo Manapat’s 1991 book, Some are smarter than others: The history of Marcos’ crony capitalism.

A year before Manapat’s book came out, Sugarlandia’s top Marcos crony entered into a compromise agreement with the Presidential Commission on Good Government in 1990, surrendering about US$16 million worth of Swiss bank deposits, shares in 32 corporations, including all of his shares in the California Overseas Bank, cash dividends in his firms, and 51% of his agricultural land holdings.

Gold for the cronies, starvation for the masses – Martial law worsened systemic injustices on the island, turning it into a social volcano.

In the Hiligaynon language of the island’s Occidental side, two words define hunger.

Gutom refers to the normal pangs when the next meal is delayed for an hour, or two, or even half a day.

Tigkiriwi is the gnawing in the guts and moaning in the minds of folk who have not eaten for days, or who are reduced to a meal of thin gruel a day.

Sugar workers were familiar with tigkiriwi, which haunted their hovels during the dead season, the Tiempo Muerto between planting and harvest seasons, when income from piecemeal or daily jobs dried up for three or four months.

But by 1980 to 1985, on the rich, volcanic earth of Negros, the country’s fourth-largest island, tigkiriwi stretched for years.

Fortich called the phenomenon Tiempo del Muerto, a Time of Death.

“At the start of the sugar crisis, many workers went to the city where they tried to find odd jobs,” Onion said. “Of course, there were none because Bacolod was dependent on the sugar industry.”

Too late for victims of plunder

At the provincial hospital, the crisis slithered in with a trickle, and then a flood of children with swollen bellies, stick-like limbs, straw-like, dry, orange-tinged hair, and eyes that stared into an abyss of pain.

In the “golden age” touted by the dictator’s namesake, now the 17th president of the Philippines, a boy named Joel Abong died in the arms of Onion in 1985.

He was around seven years old, with a baby’s body. Joel had pneumonia and tuberculosis. A rattle signaled every desperate effort to breathe. Doctors wrapped padding around limbs gone brittle with nutritional deficiency

“There have always been many malnourished children. By the time they landed in the hospital, it was almost always too late,” Onion said.

“You see, in the haciendas, malnutrition was a fact of life. Sugar workers did not have money to go to clinics and hospitals, so they tried to care for their children until they got very sick,” he explained.

Joel landed on the covers of magazines, a symbol of the “Batang Negros,” child victims of a disaster spawned by greed, corruption, tyranny, and a long entrenched system of injustice.

In August 1985, 10% of Negros’ children were suffering third-degree malnutrition, according to Dr. Violeta Gonzaga of La Salle College, Bacolod. The National Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW) said a quarter of children had milder forms of malnutrition.

The crisis’ impact would last for years.

“Every fifth child on the island under the age of six in 1986 was found to be seriously malnourished, former Oxfam America overseas head Michael F. Scott wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 1987.

A US Congress 1988 report on foreign aid programs cited the National Nutrition Council of the Philippines as saying 350,000 children in Negros Occidental or 40% of children under the age of 14 were malnourished in 1985.

Fortich released millions for starving families. The diocese expanded daily feeding operations to 27 rural areas, using the network of the Kristiyanong Katilingban, an organization of the laity that was a frequent target of military and police harassment.

“It was like swimming against giant waves,” Onion said.

Social volcano erupts

As children died, protests grew massive, even as state repression spiked. Fortich called Negros “a social volcano” and 1985 saw the biggest eruptions of people’s rage.

“Regularly, we would see in the fields bodies of sugar workers salvaged by soldiers,” said Errol Gatumbato, a former staff of Task Force Detainees in the province.

State violence reached a peak in Escalante, on September 20, as thousands joined a Welgang Bayan (People’s Strike) on the eve of the anniversary of the declaration of Martial Law in 1972.

Twenty persons died on the hot asphalt pavement as paramilitary troops of Armin Gustilo, another Marcos crony, opened fire with a machine gun.

Members of the Civilian Home Defense Forces (CHDF) fired armalite rifles as they chased hundreds of fleeing protesters in the sugarcane fields around the town center.

Decades later, survivors would still weep with every recollection.

The current President Marcos continues to evade acknowledgment of the realities of his father’s dictatorship and the violence and plunder it spawned.

San Carlos Bishop Grerardo Alminaza said the dictator’s heirs have led “the systematic erasure of the historical truth. The truth remains – that the Martial Law regime plundered our nation’s wealth and committed massive human rights violations.”

“Describing the Martial Law period as a ‘Golden Age’ is a historical distortion and we reiterate our call to end the massive disinformation that escalated in the last presidential elections,” Alminaza said in a statement on the 50th anniversary of the declaration of Martial Law.

– Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.