SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

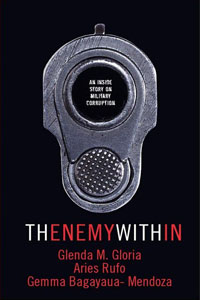

(Editor’s note: On Wednesday, April 10, the Sandiganbayan upheld the plea bargain deal entered into by retired military comptroller Carlos Garcia and the Office of the Ombudsman. The controversial deal allowed Garcia to escape plunder charges. The book “The Enemy Within,” written by Glenda M. Gloria, Aries Rufo and Gemma Bagayaua-Mendoza looked into this deal. We are reprinting excepts from the chapter on the Garcia deal written by Aries Rufo.)

MANILA, Philippines – The senior prosecutor’s words carried an air of resignation: “I just cannot stomach the plea bargain.” He was on the phone with a colleague who had called him to ask why he had suddenly become inactive in the Garcia plunder case. The senior prosecutor said, “This is going to explode. The deal has been submitted to the Sandiganbayan for approval.”

It was December 2010, and word had already leaked that the Office of the Special Prosecutor (OSP) had entered into a plea bargain deal with the disgraced retired Maj. Gen. Carlos Garcia. It was about the withdrawal of the plunder case filed against him in exchange for pleading guilty to the lesser offenses of indirect bribery and facilitating money laundering. The plea bargain required Garcia to surrender to the government his real estate properties, shares of stocks and bank deposits amounting to P135 million—which is not even half of the P303 million that he was accused of amassing. More importantly, it allowed him to post bail and spend Christmas at home after 5 years in jail.

It was December 2010, and word had already leaked that the Office of the Special Prosecutor (OSP) had entered into a plea bargain deal with the disgraced retired Maj. Gen. Carlos Garcia. It was about the withdrawal of the plunder case filed against him in exchange for pleading guilty to the lesser offenses of indirect bribery and facilitating money laundering. The plea bargain required Garcia to surrender to the government his real estate properties, shares of stocks and bank deposits amounting to P135 million—which is not even half of the P303 million that he was accused of amassing. More importantly, it allowed him to post bail and spend Christmas at home after 5 years in jail.

A tsunami of protests greeted the deal that the prosecutors attempted to keep under wraps. With the imprimatur of then Ombudsman Merceditas Gutierrez, it was hammered out by Garcia and his lawyer on one side and 5 state prosecutors on the other: Wendell Barreras-Sulit, Jesus Micael, Robert Kallos, Jose Balmeo, and Joseph Capistrano. Of the 5, only two—Balmeo and Capistrano—were part of the original team that prosecuted the ex-military comptroller for plunder. The rest entered the picture only when the plea bargain talks were about to begin.

The agreement was finalized only less than 3 months after a special division of 5 justices threw out Garcia’s petition for bail in a 3-2 vote, on Jan. 7, 2010. The verdict, however tight, meant that up to that time, the court was convinced that the evidence of plunder against him was solid.

Yet, the prosecution and defense still proceeded with the joint motion for approval of the plea bargain agreement, triggering public outcry that plunged the career of some, and raised the stock of others. It prompted a Senate investigation that pushed former Defense Secretary Angelo Reyes to commit suicide.

Although the plea bargain deal was not among the listed complaints, it put the spotlight on Merceditas Gutierrez, who quit just before the Senate was to begin her impeachment trial in May 2011. It made instant self-styled heroes and heroines, as in the case of former Lt. Col. George Rabusa, who spilled the beans on the alleged “pabaon” system in the military, and former auditor Heidi Mendoza who was later appointed commissioner of the Commission on Audit.

What happened?

Based on court records and interviews with people privy to the case and Ombudsman insiders, we discovered that:

• The real estate properties and deposits that Garcia supposedly surrendered in the deal were already the subject of two forfeiture cases in the Sandiganbayan’s Fourth Division, which was not even informed about the plea bargain deal.

• Gutierrez only showed token interest in the case. She hardly supported the team that prosecuted Garcia.

• Despite the importance and complexity of the case, it was a former Public Attorney’s Office (PAO) lawyer, who had indigents as former clients, who was assigned to handle it. From a mere “coordinator” of the team, this prosecutor assumed the burden of a lead prosecutor when the original prosecutors got promoted or refrained from further handling the case.

• The prosecution rested its case only on two pieces of evidence: the written statement of Garcia’s wife, Clarita, and the testimony of Heidi Mendoza on the supposed missing P50-million fund from the United Nations’ reimbursements to the Philippine military.

• Witnesses called to buttress Mendoza’s testimony debunked the former auditor’s court statements. Mendoza’s testimony also crumbled during cross-examination by Garcia’s lawyer.

• Despite its vast powers, the Office of the Special Prosecutor and the Ombudsman failed to persuade a single military supplier that supposedly provided bribes to Garcia to testify.

“We were beaten to the draw by the defense in talking to those suppliers,” one prosecutor admitted.

Thus, this is a classic story of how the big fish got away without trying too hard. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.