SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Simmering tension between the executive and judicial branches of government has been evident in recent exchanges over the hotly-debated Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP).

While the executive asserts its power to implement programs and projects it deems necessary to push economic growth, the High Court wants to make sure these are all within the bounds of the Constitution. When he appeared before the Senate on July 24, Budget Secretary Florencio “Butch” Abad insisted that DAP was innovative governance.

Earlier on July 1, the SC declared unconstitutional key acts under the administration’s DAP. These include: the declaration of savings contrary to the definition of the General Appropriations Act (GAA) and its subsequent transfer to another budget item; the cross-border transfer of alleged savings from the executive branch to another branch of government; and the transfer of funds to items not part of the GAA.

This move by the SC has evolved into a battle of wills between the judiciary and the executive branches of government, with President Benigno Aquino III publicly criticizing the Court for its decision. In his televised address to the nation on July 14 where he defended the DAP, he unleashed what was seen to be a veiled threat of impeachment against the justices: “My message to the Supreme Court: We do not want two equal branches of government to go head to head, needing a third branch to step in to intervene.”

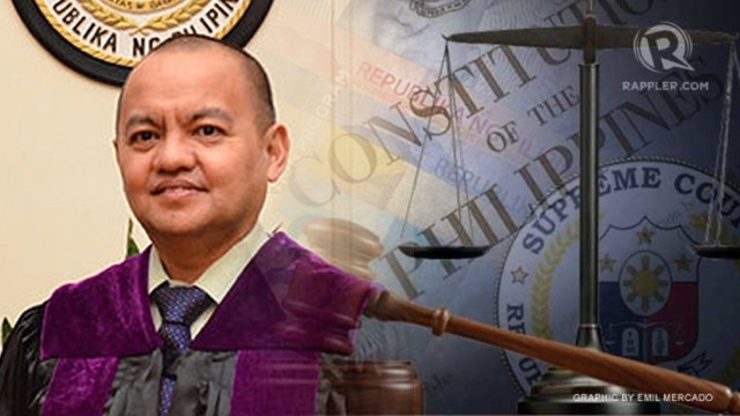

Among the separate opinions submitted by the SC justices, the 29-page concurring opinion of Associate Justice Marvic Leonen is perhaps the most sympathetic to the case of the executive. Yet in his final note, Leonen warned that “our passion for results might blind us from the abuses that can occur. In the desire to meet social goals urgently, processes that similarly congeal our fundamental values may have been overlooked. After all, “daang matuwid” is not simply a goal but more importantly, the auspicious way to get to that destination.”

While cognizant of the importance of executive discretion within the bounds of the law, Leonen wrote that judicial review is also a discretion that should be wielded by the Court with “deliberation, care, and caution.” He added that the Court’s pronouncements should be tailored to the facts of the case so as not to “unduly transgress into the province of the other departments.”

At the same time, he made a strong case for fiscal autonomy on the part of the judiciary. The judiciary has been hit for its independent use of the Judiciary Development Fund (JDF), with proposals surfacing in Congress to have the JDF remitted to the national treasury.

With Congress known to have the power of the purse, observers have noted that the President may very well rally for his allies in Congress to threaten the judiciary with a lesser share of the budget pie. The President has, in fact, criticized the judiciary for allegedly also using a DAP-like mechanism within its budget. (READ: Court employees slam Aquino for ‘rampage’ vs judiciary)

As if responding to these, parts of Leonen’s opinion on the DAP address these issues. He also expounds on other key points:

1) The importance of the judiciary’s fiscal autonomy

Leonen said the judiciary is fiscally autonomous: “… the constitutional protection granted to the judiciary is such that its budget cannot be diminished below the amount appropriated during the previous year.” He added that the annual submission of the judiciary’s outlined expenditures is “only for advice and accountability; not for approval.”

“Any additional appropriation for the judiciary should cover only new items for amounts greater than what have already been constitutionally appropriated,” he wrote.

The judiciary’s fiscal autonomy would mean that it can use its budget for its own operations the way it sees fit.

2) Realignment of funds is different from augmentation of items, and the President is allowed to realign funds

Leonen explained that prioritization in government spending is important, given the system of budgeting. Given realities of the budget process, he recognizes the need for “flexibility” to allow the President to make decisions “subject to clear legal limitations.”

Realignment means moving allocations from one budget item to another item which has insufficient funding; it is meant to fund a deficiency only in an existing budget item.

This recognizes that it is Congress, through the enactment of the GAA, that sets the maximum allocation per item in the national budget. These allocations are, however, premised on the assumption that money through taxation, among others, can be collected by government. But not all budget items may have actual funds equal to their allocations outlined in the GAA. For purposes of prioritizing, the President can thus move existing money from one budget item to another, without exceeding the maximum funds allotted for it. This is realignment, which Leonen differentiates from augmentation. (READ: President should only augment deficient items, SC told)

Augmentation, he explained, is the use of savings from one item to add to the budget of another item. This means that savings would have to be identified, and that the budget item receiving the additional fund would exceed its maximum allotment set by the GAA.

The Constitution, Leonen explained, prohibits cross-border transfer of funds for being “violative of the doctrine of separation of powers.” Differentiating between realignment and augmentation, he also wrote, “Unlike in augmentation, which deals with increases in appropriations, realignment involves determining priorities and deals with allotments without increases in the legislated appropriation.”

3) Where there are irregularities in a project allocated funding, the President may augment another item using funds from an irregular project

In the name of fiscal responsibility, Leonen said “the President can withhold allocations from items that he deems will be ‘irregular, unnecessary, excessive or extravagant.'” Disagreeing with Justice Antonio Carpio on this power of the President, Leonen said it would be an “abuse of discretion for him not to withdraw the allotment or withhold or suspend the expenditure” when it is associated with a project tinged with irregularities. Going further, Leonen also wrote that these funds may be considered “savings” and be used to augment other budget items, still within the bounds of the Constitution.

Carpio had written that to grant the President the power to suspend the expenditure of unobligated funds is like giving him the power of impoundment, or a refusal to implement the GAA as is. Carpio said the President should only be able to use his “line veto power” prior to the allocation of funds to an item. Once appropriations are allotted and enacted into law, the President can no longer suspend these items. Carpio argued, in effect, that impoundment allows the executive to reverse the will of Congress.

“Savings” however are required to augment items in budget appropriations. The GAA defined savings as being “free from any obligation or encumbrances” which, to Leonen, requires any of 3 situations in relation to a project: “completion, final discontinuance or abandonment.” The suspension of an irregular project could thus generate funds for realignment or “savings” to augment existing items in the budget within the same branch of government.

Leonen also disagrees with Carpio on setting timelines for the declaration of savings, citing nuances in executing a budget. “To so hold would be to impinge on the ability of the President to execute laws and exercise his control over all executive departments.”

4) Suspension of a project on valid grounds is not impoundment

Leonen said the prohibition against impoundment is “not yet constitutional doctrine.” Given this, the SC cannot make a blanket ruling on the issue, especially in the absence of an actual case presented before it. He added that no such case of impoundment alleged by petitioners against the DAP exists that would allow the Court to rule on it.

“The difficulty in making broad academic pronouncements is that there may be instances where it is necessary that some items in the appropriations act be unfunded,” he explained. This may perhaps include projects that need to be abandoned for other valid reasons. For instance, in deficit situations, it may be wise to refuse to fund a project to be able to implement other priority projects. Otherwise, “attempting to partially fund all projects may result in none being implemented.”

For impoundment to be sound constitutional doctrine, there must be “evidence of willful and malicious conduct on the part of the executive to withdraw funding from a specific item other than to make priorities,” Leonen wrote.

5) Doctrine of operative fact

Leonen wrote that to rule that the Court’s declaration of unconstitutionality of the DAP per se is the basis for determining liability “is a dangerous proposition.”

Any discussion on bad or good faith on the part of those who conceptualized or implemented the program is “premature,” he said, adding that the “presumption of good faith is a universal one.” The Court’s decision should not be “immediately used as basis for saying that any or all officials or beneficiaries are either liable or not liable.”

He differed with Carpio who said the doctrine cannot be invoked by those who acted in bad faith, and with Brion, who said establishing good faith can be made “only by the proper tribunals” and not the Supreme Court. – with reports from Buena Bernal/Rappler.com

See related stories:

- Understanding the SC ruling on the DAP

- Highlights: Carpio’s separate opinion on DAP

- The DAP decision: Lessons on politics, governance

- Aquino hits SC, insists DAP is legal

- Abad: I take full responsibility for DAP

Read more stories on the DAP here.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.