SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

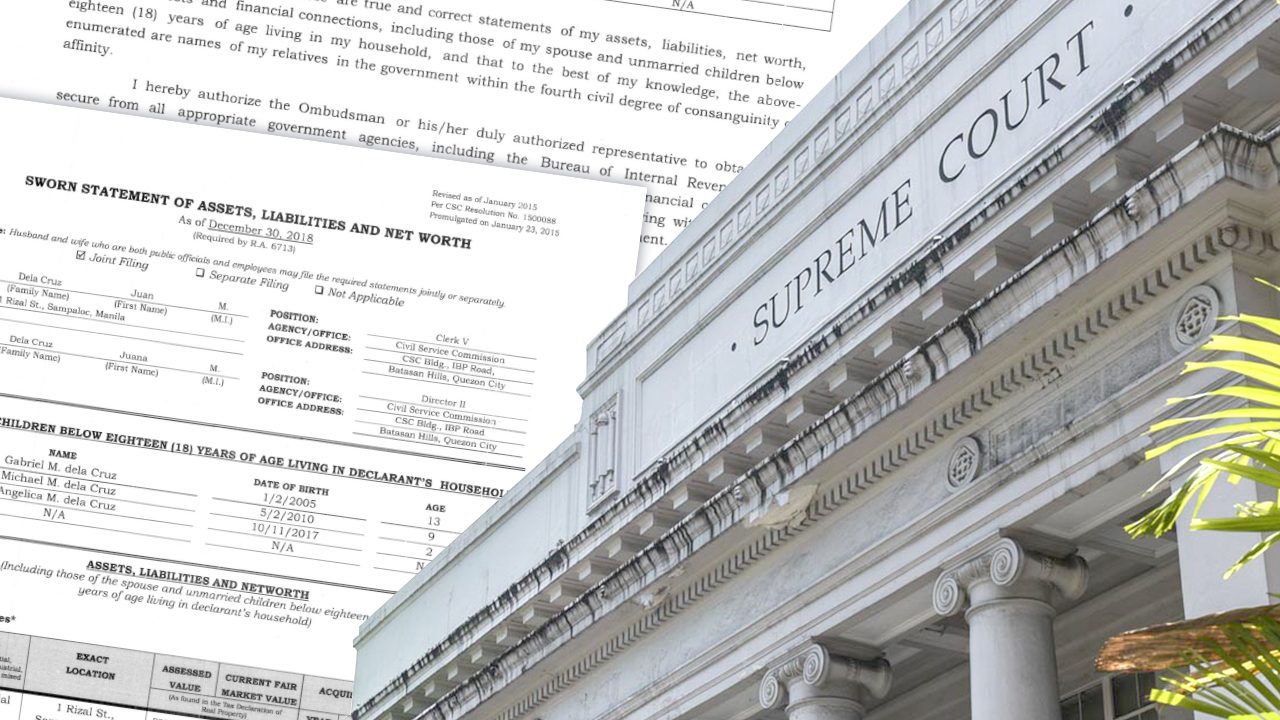

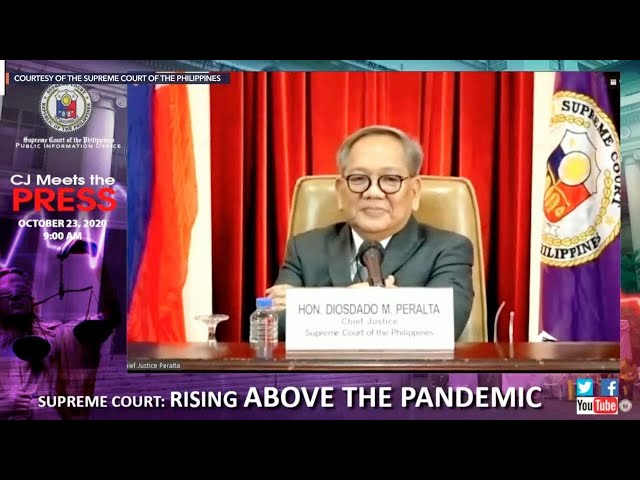

“If you have some interpretations about that, it’s up to you but we just follow the existing rule,” was all that Chief Justice Diosdado Peralta could say when asked about the unanimous decision not to release to the Solicitor General the Statements of Assets, Liabilities, and Net Worth (SALNs) of Associate Justice Marvic Leonen.

The questions were: Was the Supreme Court protecting Leonen or the institution from quo warranto threats? How would he reconcile the restriction when he concurred in the decision to oust former chief justice Maria Lourdes Sereno on the basis of her SALNs?

“There’s not yet any rule on that if we can release the SALN. Until that resolution is amended, that should be the case,” Peralta told quizzing reporters in a rare press conference on October 23.

Peralta was referring to A.M. No. 09-8-6-SC, a post-Renato Corona resolution that required people to justify to the en banc the basis of their request for the SALNs of members of the judiciary, including judges.

“Requests for SALNs must be made under circumstances that must not endanger, diminish or destroy the independence, and objectivity of the members of the Judiciary in the performance of their judicial functions, or expose them to revenge for adverse decisions, kidnapping, extortion, blackmail or other untoward incidents,” says the resolution.

For reasons still unknown, the en banc unanimously rejected the request of the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) to obtain Leonen’s SALNs for purposes of initiating a quo warranto procedure.

“If we allow the release of SALN, in toto, you can just imagine the judges who decided against somebody, all of those, they will know the addresses of the judges, they will know where their children go to school. That’s why, we are also not only protecting ourselves but protecting also those judges in the lower courts,” said Peralta, not directly answering the questions.

‘It can’t be reconciled’

Peralta is correct – A.M. No. 09-8-6-SC is a standing rule.

But how can they reconcile an institutional view of restricting access to SALNs and ousting a chief justice because of alleged non-filing of SALNs?

“Well, I don’t think it can be reconciled quite honestly,” Constitutional Law professor and political analyst Tony La Viña told Rappler in an interview for the Law of Duterte Land Podcast.

“In terms of principle yes (it’s an irony), you can actually see that in the dissents, that there were two types of dissents, one is the process and the other one is the use of SALNs as a way of making a judgment of a person, if a person is not a person of integrity. You have to remember the removal of Sereno is on the qualification that she had no integrity,” said La Viña.

The Supreme Court found that Sereno did not file some of her SALNs when she was a law professor at the University of the Philippines (UP). The Constitution says a member of the Supreme Court must be of proven integrity.

“Compliance with the Constitutional and statutory requirement of filing of SALN intimately relates to a person’s integrity,” said the Supreme Court in the quo warranto decision penned by retired associate justice Noel Tijam.

Two different things

Here’s where Lyceum Political Law lecturer Carlo Cruz makes a distinction: The issue of non-filing of SALNs is separate from the issue of releasing filed SALNs.

Sereno allegedly did not file her SALNs, while the Supreme Court is just restricting the release of filed SALNs.

“The Court, in Republic vs Sereno, considered non-filing as a matter of integrity, a subjective attribute required for eligibility for nomination to become a judge,” said Cruz, who was one of Sereno’s spokespersons during the impeachment proceedings.

“I do not see any clear or direct relationship between this and the present determination of the Court not to release filed SALNs,” said Cruz.

Does this conundrum highlight what is obvious in legal and political circles – that while the Supreme Court does not judge a member of the judiciary on the basis of his or her SALN alone, the magistrates used it because it was the only way at the time to oust a chief justice they didn’t like?

“It’s hard to say that but from a political point of view, that’s what seems to be the case because there was an impeachment going on. There was going to be a trial…and political analysts said that (the House prosecution) could not get the 2/3 votes there,” said La Viña.

In his dissent to the narrow, but historic, 8-6 decision, Associate Justice Benjamin Caguioa said: “No matter how dislikable a member of the Court is, the rules cannot be changed just to get rid of him, or her in this case.”

SALNs: Glorifed or weaponized?

There are a lot of legal nuances here but for the ordinary person, a basic question is: if you have nothing to fear about your SALNs, why hide it?

La Viña agrees with Ombudsman Samuel Martires that SALNs had become weaponized. For La Viña, SALNs are valuable forensic tools for trained investigators and prosecutors to determine hidden or ill-gotten wealth.

But when they land in the hands of politicians, for example, SALNs become a tool for an unfair fishing expedition.

“These are not graft and corruption investigators, but these are congressmen who already have a predisposition to impeach you because they have already politically decided that they will do that,” said La Viña, referring to the Sereno impeachment process.

There’s also the argument about what SALNs are for. According to La Viña, before Corona, public officials were “very careless” about their SALNs.

“A SALN was more of a technical requirement that people in government had to meet and submit every year. Most people actually just did pro forma submissions, especially because most people don’t have a lot of properties anyway, a lot of assets and liabilities,” said La Viña.

But with the Sereno ouster, the Supreme Court “glorified the SALN, and said if you did not submit the SALN, you must have no integrity,” he added.

“The SALN as a requirement is precisely about, in my view, transparency of your income to show that you did not benefit from your government position, that’s really all there is. So even if you did not submit a SALN, if there’s nothing that can be proven, that doesn’t make you a person of less integrity, [it] simply means that you did not submit the requirement like other requirements,” said La Viña.

There’s also the issue of SALNs only having a 10-year shelf life. Section 8(c)(f) of the Code of Conduct says that after 10 years, the SALNs may “be destroyed unless needed in an ongoing investigation.”

Release to the media

The Supreme Court released only summaries of justices’ SALNs but it stopped doing so after 2017. Beginning 2020, for the 2019 SALNs, the Supreme Court now requires requests to be notarized.

In this aspect, the judiciary joins all branches of government in opting to be less transparent about SALNs. Congress had also required notarization of requests for lawmakers’ SALNs.

And the most recent is Ombudsman Samuel Martires’ Memorandum Circular restricting public access to SALNs in the custody of his office, including that of President Rodrigo Duterte.

In Martires’ new rule, only the official concerned can authorize the release of his or her own SALN, but Malacañang keeps passing the buck.

Cruz said requiring notarized requests may be deemed “reasonable” by virtue of the post-Corona resolution, but he said no official has the power to “deny or prohibit reasonable requests for documents.”

This is also what the Supreme Court said in the same resolution: “Such discretion does not carry with it the authority to prohibit access, inspection, examination, or copying of the records. After all, public office is a public trust.“

Cruz said, “I think that these most sound statements of the Court essentially affirm that SALNs are precisely ‘weapons’ granted under the Constitution in favor of well-meaning citizens, including of course the press, which they may use or invoke for purposes of lending true meaning to the concept of public accountability in our Constitution.”

The point of former ombudsman Conchita Carpio Morales is this: That the SALNs may be weaponized is a separate issue, and what matters is that the Code of Conduct is clear they can be made accessible to the public. (READ: Does Martires’ SALN restriction violate Code of Conduct?)

Section 8(C)(4) of the Code of Conduct says SALNS “shall be available to the public for a period of ten (10) years after receipt of the statement.”

Morales said in an earlier interview on ANC’s Headstart, “If he believes that this is being weaponized by enemies, then that is the concern of the politician, but no one can refuse the request of anyone to use a SALN or copy the SALN for as long as it is not against morals or public policy.”

She added, “(The circular) goes against the constitutional principle that public office is a public trust.”

La Viña said that the media can argue that they are what the law meant by “the public.”

“I think that the media would have a chance by citing the constitutional status of the SALN,” he said.

La Viña added that the judiciary has a better reason to restrict access to SALNs more than the executive branch, including Duterte.

“You always have to remember that the judicial power is the power to decide disputes. When you decide disputes, you rule for one against another. So we have to protect people who make those decisions,” said La Viña.

“In the executive, most of your job is getting things done,” he added.

For the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ), no matter which branch, all the issues boil down to one thing: transparency.

PCIJ said: “As SALN custodians become more and more restrictive, journalists lose a key document crucial in investigations that have shed light on the wealth and business interests of government officials, including past presidents like [Joseph] Estrada, [Gloria Macapagal] Arroyo, [Benigno] Aquino [III], and the incumbent, Duterte.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[EDITORIAL] Bakit galit tayo sa lumunok ng dolyares pero keber lang sa confidential funds?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/09/animated-airport-security-money-eating-corruption-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.