SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Part 2 | Averting disaster: How Cebu City flattened its curve

Six months after the coronavirus prompted a lockdown in the busiest metropolitan city outside of the capital, data scientists from the University of the Philippines’ OCTA research group and the Department of Health said Cebu City had flattened its curve.

This was the first time they said this about any city since beginning their bi-monthly reports on local coronavirus data from March.

But things could have turned out much differently if Cebu City did not get its act together after the same research group sounded the alarm back in June about the number of rising cases then.

OCTA called Cebu City the “second major battleground” in the country’s fight against COVID-19. From a few dozen cases in early April, the numbers skyrocketed to the thousands by early June.

In May, Cebu was the city with the most number of cases in the country. By mid-June doctors were also reporting that COVID-19 beds were full.

How did the coronavirus cases explode in one of the cities better equipped and capable of responding to a health crisis?

Busy metropolis

Cebu City is in the center of the second-biggest metropolitan area outside of Metro Manila.

The population of Metro Cebu is about 2.8 million people. It has an international airport, seaport, and the tourism and economic activity of the region is as busy as any cosmopolitan city around the world.

Dozens of high-density urban-poor neighborhoods are scattered throughout the city’s lowland barangays.

According to an article in science magazine Scientific American, while high-density itself is not necessarily a guarantee of an outbreak, if this factor is coupled with a high level of tourism and business travel, then the city would be more susceptible to becoming a virus hot spot.

“Despite the fact that the first lightning bolt could have struck anywhere, large cities like New York, Seattle and Los Angeles have a bias to attracting them,” Scientific American said in its report. “They are all commercial hubs with a large influx of tourism and business travel. Infectious disease is not randomly placed across cities,” it said.

The authors also said that outbreaks are aimed at cities like New York and Los Angeles because of the number of people coming in and out. “It is not an historical accident that we see the COVID-19 outbreaks happen in these cities first,” the report said.

Cebu is not any different from these cities.

From January until the airports were shut mid-March, thousands of passengers were able to come to Cebu through flights from China through the airport.

One of the earliest confirmed cases, in fact, came through here via Hong Kong on January 20, only a day after the Sinulog Festival, where an estimated 1.5 million to 2 million foreign and domestic tourists were in attendance.

A face mask mandate had not yet entered the public consciousness at the time, with the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF) recommending face masks only by March.

The World Health Organization was even slower, recommending universal mask wearing as a protection measure against the virus only in June.

But with the known 14-day incubation period of the virus, it is impossible to know now how many tourists brought in the virus to Cebu that way during the Sinulog Festival.

While these activities were happening, there were very few swab kits available.

Cebu City’s COVID-19 RT-PCR lab at the Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center did not open until March 20.

Prior to that, all swabs were being sent to the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM) in Metro Manila, a lab that was already dealing with massive backlogs from Metro Manila samples.

There were several cases of patients showing up in hospitals with influenza-like illness and even dying while waiting for their results. So by the time the lab opened in Cebu City, health agencies and local government units were already having to play catch up.

Slow to move

But to be fair to Cebu City, like the rest of the world, the local government had been acting on limited data and info about this virus as it emerged only at the end of December 2019.

Not preparing testing labs and contact tracing teams is a lesson many cities around the world learned the hard way, including Cebu.

From the time the virus was discovered, until the lockdown, the local government units began implementing its anti-coronavirus policies piecemeal.

In the early days of the outbreak from late January to mid-March, the local and national government’s messaging focused on washing hands, covering coughs, and social distancing.

Over 6 months into the pandemic, what we know now is that aside from public information campaigns, it takes quick contact tracing, massive testing, and isolation to suppress the spread of the virus in any area.

These are essentially the basics of managing any pandemic and already outlined by the World Health Organization.

Decisive action

After Cebu itself went on lockdown on March 28, it seemed like the city was finally picking up the pace.

Six cluster clinics were set up across the city to handle patients showing symptoms.

In these clinics, patients who had influenza-like illnesses would be able to get tested for free, and those who come in close contact would also be traced and isolated.

Outbreaks in urban poor areas, jails

By mid-April, contact-tracing efforts led city health officials to conduct massive testing in the city’s most congested sitios and barangays.

The first was Sitio Zapatera.

Sitio Zapatera in Barangay Luz, just outside the Cebu Business Park is a low-income and high-density neighborhood of about 9,000 people.

Dozens of boarding houses are in the area where many food, retail, call center, and other employees rent bed spaces and rooms.

One positive case led to 3, which then led to 201 cases at its peak. By then, the contact tracers, who were only around 26 at the time, became overwhelmed. Instead of continuing to look for close contacts of the 3, Cebu City health instead declared the entire sitio “infected.”

This began the strategy of hard neighborhood lockdowns.

This meant residents without symptoms would be allowed to leave their homes for any reason and that food and supplies would be brought to them by authorities. (READ: Entire Cebu City sitio ‘presumed contaminated’)

Those with mild symptoms would be brought to the barangay isolation centers, while those with severe symptoms would be taken to the hospitals. This became the response template in responding to outbreaks in the barangays.

After Zapatera, Sitio Alaska was the next neighborhood to lock down. The area is in one of the most dense barangays with 30,000 residents.

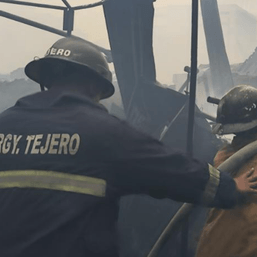

The cases in two sitios hit over 600 by June. Suba, Labangon, Tejero, and Carreta were the next barangays to have lockdowns.

Cases in the city and provincial jail also increased exponentially around this time, peaking at 400 active cases.

At the time, the local health agencies explained that they were aggressively testing people, that’s why the numbers were rising. However, in June, the Department of Health reported that Cebu City’s positivity rate – or the percentage of individuals testing positive – was highest at 32.8% between June 16 and 24.

In comparison, Metro Manila’s positivity rate was at 7.2%, still above the World Health Organization’s 5% standard positivity rate – a sign that a locality has the pandemic under control.

After May, however, there was not much localized data on how the virus spread geographically because the data reports stopped.

Spinning the data, covering up an outbreak

Between May 21 and May 27, there were zero data reports released by DOH-7.

When asked for an explanation, the DOH-7 said they were conducting a “database update and cleanup.”

They began sending the missed updates from May 21 onwards on Wednesday, May 27, and were fully updated on their data reports by early June. But during this period, the data sheet changed. It contained a timeline of cases, a breakdown by gender and age, newly confirmed cases per date, and the status of previous cases.

They also included a graph highlighting co-morbidities of those who died and a comparison to infections from other unrelated diseases. For example, the May 27 bulletin highlighted that 8,150 cases of dengue were confirmed from January 1 to March 31 this year, the early period of the coronavirus outbreak.

This is similar to the line the provincial government, led by Governor Gwendolyn Garcia, pushed at the height of the COVID-19 outbreak in May.

In the province, patients who tested positive and who died, but had other conditions like hypertension or diabetes, were recorded as “incidental” deaths.

The way the information was presented by the local government officials and health agency heads themselves seemed to paint a picture that everything was well-managed up to the end of May.

Shortly after the data access was restricted, the city successfully petitioned the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases to lower its quarantine status to General Community Quarantine.

The current local head of COVID-19 response Joel Garganera said himself that it was also during this period when the city “dropped the ball.”

“Actually we really dropped the ball there,” Garganera said on August 2, during a Rappler Talk interview. “As I said that’s the reason, we really dropped the ball and then aggravated by the fact when it downgraded to a lower quarantine status so people just went out. That’s when the President said gahi’g ulo (hard-headed),” he added.

It was during this period also that the hospitals became full. This was a sign that the worst was yet to come. And the President, whose family originally hails from this city, would have to step in. – Rappler.com

Part 2 | Averting disaster: How Cebu City flattened its curve

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.