SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

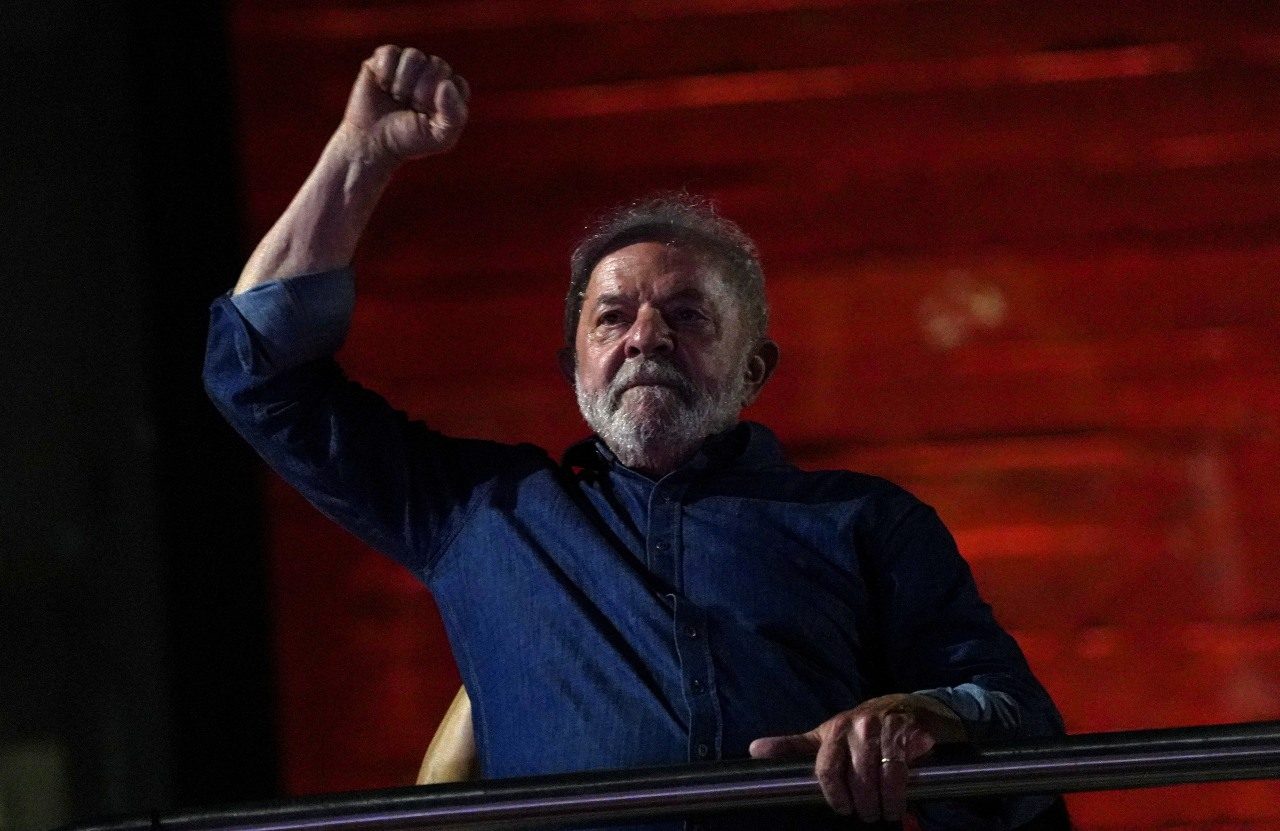

MANILA, Philippines – In one of the closest races for the presidency in Brazil, Luis Inacio Lula da Silva beat the incumbent Jair Bolsonaro to retake the country’s highest post. The victory marked the comeback of the leftist leader against a far-right administration, and for many watching around the globe, roused hope in a struggle to defend democracy worldwide.

On the campaign trail, Lula spelled out the high stakes: “Our campaign is a campaign with a fundamental goal: to restore this country,” he said.

Political observers had also taken note that Brazil’s democracy was on the ballot during its recent polls and that a win for Bolsonaro, nicknamed the “Trump of the tropics,” would see the country slide further toward authoritarianism. For now, Brazil defied such an outcome.

Still, Lula’s win does not mean Brazil’s democracy is in the clear. Though his victory was welcomed across the world, the bitter fight between Lula and Bolsonaro – who won 49% of the vote – displayed that right-wing politics remained a potent force and popular option for many in the Latin American country.

What should countries like the Philippines and forces seeking to defend democracy learn from Lula’s victory?

Opposition forces must be resilient

Lula’s return to power comes nearly 10 years after he held Brazil’s highest post. In the years between, he faced corruption charges relating to a vast government kickback scheme that took place during his administration, leaving many to believe it would be the end of his political career.

The conviction saw Lula in prison for 580 days, until a Supreme Court ruling threw out his cases, citing findings that the judge involved in those cases was biased. While many in Brazil continue to see Lula as corrupt, strong opposition against Bolsonaro and his policies, as well as his brand of far-right movement, fueled Lula’s return to the presidency.

“The greatest lesson that we can learn from the Brazil case…is for the opposition forces to be resilient,” political scientist Arjan Aguirre of the Ateneo de Manila University said. “They should really know who they are, learn how to make use of what they have, understand what electoral rules are in place, see different practices and tendencies that shape the electoral process.”

Lula’s victory, observers noted, showed how Brazil’s opposition took its role to heart. To mount his comeback, Lula and his allies mobilized networks and resources cultivated over years by political parties in his coalition, and maximized programs previously implemented by Lula during his last presidency. This included the “Bolsa Familia” social services program which saw low-income families receive a stipend in exchange for making sure their children attended school and stayed up to date on vaccinations, much like the Philippines’ 4Ps program.

“Winning an election is just the result of this long process of politicizing the space given them as an opposition,” Aguirre said.

“They (opposition) should also see themselves as government-in-waiting. They should always appear that they are capable of governing the society anytime the need arises,” he added.

Unity is key

As a union leader in the 80s, Lula managed to organize thousands of trade union groups into a political party called PT or the Workers’ party. The group had the backing of Brazil’s liberal Catholics, indigenous groups, working class, and Afro-Brazilians, among others, and would later provide the platform for Lula’s coalition building in the coming years.

Lula ran for the presidency three times before finally securing the post for the first time in 2003. But each election run saw him earn the support of various groups across the political spectrum, expanding his base. In 2002, he later brought in members of some conservative parties into his fold, allowing him to broaden his base further.

Lula’s political journey shows that “a major political upset does not happen overnight,” Aguirre said.

Strong party systems likewise aid in coalition-building, with loyalty among political party members stemming more from ideology than personality. This stands in contrast to countries like the Philippines, where personalities and political dynasties rule.

“Left parties are also not vilified (red-tagged) by many sectors. They are seen as legitimate competitors in politics with clear party programs,” political scientist Ela Atienza of the University of the Philippines said.

Brazil’s electoral system with run-off elections was another factor that pushes political parties to compromise and build coalitions, and present clearer alternatives to voters.

“The second-round voting really forces parties to get more support by courting losing parties in the first round. This promotes the practices and culture of coalition-building, negotiations, compromises,” Aguirre said.

Lula and his supporters did the same in the 2022 polls. He garnered the support of eight of Brazil’s former presidential candidates from both left- and right-leaning parties and gained the backing of its business community.

“Lula has made a front that maybe cannot get broader,” Gustavo Ribeiro, founder and editor of The Brazilian Report, told Vox.

Brazil’s recent election illustrates that “social movements and political parties must be strengthened in the Philippines to counter the outsized influence of dynasties and elitist parties,” Atienza said.

Aguirre added, “The usual pattern that we are seeing among the latest electoral victories over far-right parties is the alignment of left and center-left forces forming a majority coalition capable of winning elections and dominating a parliament.”

Autocratic forces continue to gain support

While Lula’s victory saw the defeat of Bolsonaro’s far-right administration, the close fight between the two politicians shows that right-wing politics continues to thrive and remain in the mainstream.

Riberio pointed out that Bolsonaro’s brand of politics will likewise be a force Lula and his supporters will contend with in the years to come.

Beyond Brazil, many countries around the world face the same reality. According to Freedom House, a group that keeps track of the state of global democracy, countries that have made gains in democracy over the last 16 years have been outnumbered by those that have seen a decline.

“The current state of global freedom should raise alarm among all who value their own rights and those of their fellow human beings,” it said.

In many countries where right-wing politicians are in power, leaders captured government through the democratic route of elections, Aguirre noted. This includes the recent victory of Giorgia Meloni of the right-wing Brothers of Italy and of Benjamin Netanyahu as prime minister of Israel.

Across the world, autocratic forces also saw increases in support despite recent electoral setbacks.

“For instance, despite Marine Le Pen’s loss this year, her party saw an additional 41% of the total vote in the runoff elections compared to what she received in 2017. Trump’s loss in 2020, too, saw an additional 1% in the total vote share compared to his 2016 performance (from the roughly 62 million in 2016, his votes grew to 73 million in 2020),” Aguirre said.

He added, “We can assume that this is also the reason why right-wing parties have been persistent in contesting power these past years. They just cannot stop growing and expanding.”

‘Democracy is a never-ending process’

Leaders around the world greeted Lula’s return to power as a return to “hope” and “humanism.” The leftist leader’s victory likewise offered a new chance for Lula and other democratic forces in Latin America to prove to their people that their style of government would improve quality of life and deliver on the public’s needs.

“The Brazilian elections and Lula’s victory show that democracy and democratization are never-ending processes. Democracy needs to be consolidated, institutions strengthened, electoral promises must be delivered, and democratic support must be constantly renewed,” Atienza said.

To fall short, she added, would see hard-fought victories easily lost to populist leaders. Past the rush of an election cycle, democratic groups must also take measures to prove their worth as bearers of power, Aguirre stressed.

“Electoral victory is only one stage of the democratization process…. After electoral victory, the hard work of governing and producing results that are felt by the people begins,” Atienza said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.