SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – In a country that’s prone to natural calamities, fighting disinformation should be one of its priorities whenever disasters strike.

Every year the Philippines experiences 10 to 25 disaster events on average – 20 of which are tropical cyclones that enter the Philippine Area of Responsibility. (READ: 8 of 10 world’s most disaster-prone cities in PH)

Geographically, the country sits on the Pacific Ring of Fire, or the path along the Pacific Ocean where many earthquakes and volcanic eruptions take place. We also belong to the Asia-Pacific region, which the United Nations calls the most natural disaster-prone region in the world.

For a country that’s so vulnerable to natural hazards, it’s understandable for its people to want to stay informed each time a disaster strikes. This shouldn’t be hard, considering that worldwide, Filipinos also spend the most time online and on social media.

However, the situation in the country is not ideal. The problem is not just about the accessibility of critical information during times of crisis, but also the quality of information circulated across different media.

Why is it important to fact check during disasters?

Since almost everyone can easily go online and access social media, it’s not hard for a single Facebook post or tweet to go viral.

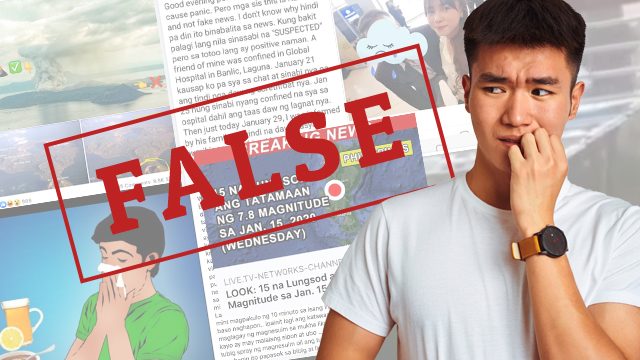

When Taal Volcano started erupting in January 2020, the country’s online space became filled with numerous reports, advisories, and even trivia about the natural calamity. While it’s good that the public could be informed by just simply tapping their phones, the problem was that not all of the readily-available information was true and accurate.

Spreading unverified information – especially exaggerated claims and warnings – only causes unnecessary panic. It could harm lives and impede – or worse, jeopardize – the response of government and private sectors.

Chain messages, in particular, spread like wildfire in times of disasters. These are urgent messages that aim to convince the recipient to pass them on to others.

Some of those who receive chain mails might believe it’s better to be safe than sorry and just pass the message on, hoping that it would help others. But that’s precisely where the harm comes from. Unverified information, especially those begging to be “forwarded” or “passed” on to others, can cause more damage than good.

Shortly after Taal started spewing ash, a chain messages circulated on messaging apps and social media urging the public to turn off their mobile phones because they could supposedly emit “strong radiation.” This was proven false, but what if those who read it actually turned off their phones, and failed to receive official advisories from the government at a crucial time?

The 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak (nCoV) was not spared from these types of messages. In January 2020, Rappler fact-checked 5 false chain mails that claimed “positive” cases of the coronavirus in the country. Here’s the harm: what if those who read the false claims of positive cases of the virus in their area believed the fake advisories more and refused to cooperate with public health officials?

In some cases, hackers even utilize disinformation to leverage fears to access computers. (READ: Malware disguised as documents with pertinent nCoV information found)

Disinformation on the 2019-nCoV outbreak was not just limited to the Philippines, too. Several fact-checking organizations that are signatory to Poynter’s International Fact Checking Network (IFCN) have collaborated to combat disinformation on the new disease, now known as COVID-19. (READ: Fact checkers worldwide team up to debunk false info about 2019-nCoV)

What can you do?

The best thing to do every time you spot unverified information online is not to spread it further and prevent others from sharing it as well.

In getting updates about a particular topic in times of disasters, it is important to look for information only from reliable sources: primary, such as government agencies and institutional experts, and secondary, such as legitimate media outlets.

But this does not mean that information released by these sources should always be taken at face value. Scrutiny is always necessary because there can be times when even public officials get things wrong.

For example, Senate President Vicente Sotto III showed a conspiracy video that claimed that the new coronavirus is a form of “biowarfare” developed by the United States against China to stop the latter’s rise as a global power. However, this theory had already been debunked by fact-checking organizations Health Feedback and Factcheck.org even before Sotto shared the video in a Senate hearing on February 4.

There are also cases where it is important to know when other forces come into play, such as censorship.

An example of this was the confusion over the death of Li Wenliang, the doctor who blew the whistle on the threat posed by the Wuhan coronavirus. He warned his colleagues of a possible deadly and unknown SARS-like virus as early as December 2019, but he was called a “rumormonger” by the Chinese government and was even detained for spreading news.

Li later on contracted the disease and died from it. Wuhan Central Hospital, also his workplace, only confirmed his death early morning of February 7, but Chinese state tabloid The Global Times already tweeted that he passed away evening of February 6. The post was taken down hours after without explanation and other outlets that published similar reports followed suit.

When these things happen, the best thing to do is to find other sources that could corroborate the claims. It’s always better to look for at least two official sources in checking a suspicious claim.

For easy reference, Rappler has listed reliable and official sources of information on volcanic eruptions and health-related concerns in light of the first two crises that hit the Philippines in 2020.

What are the elements of wrong/deceiving information?

Other posts such as a photo or graphic with no links to sources also circulate in times of crisis, along with chain mails. If you happen to see suspicious and confusing posts or messages, there are a few things to take note of before considering sharing or passing them on.

- Look for the source of the message.

Reliable advisories are from official accounts that normally include their references. Fake alerts and warnings, however, usually don’t cite sources – let alone tell you who crafted the message itself. At best, the details provided are vague and largely depend on hearsay.

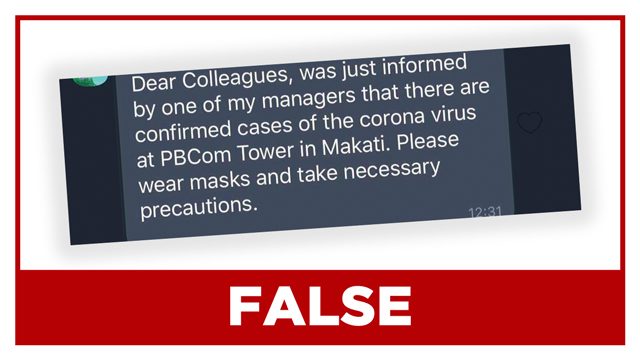

The screenshot above is one of the earliest hoaxes about 2019-nCoV cases in the Philippines. The vague chain message did not provide specific details, such as the name of the original sender and the name of the manager that confirmed the information. (READ: FALSE: ‘Confirmed cases’ of coronavirus at PBCom Tower in Makati)

- If there are sources provided, check if the information is consistent with the official reference.

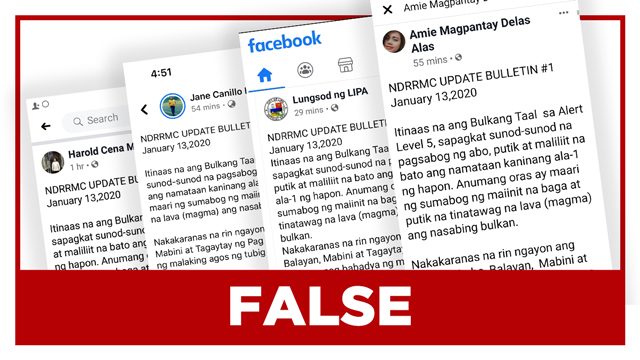

At the height of the January 2020 Taal eruption, a post about an “update” from the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) raising alert status to Level 5 became viral. This was not true, and the NDRRMC’s official website never released such an advisory.

More so, even the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) – the agency that regularly does the monitoring and adjustment of alert levels – never raised the status to level 5 in January 2020.

- Gauge if the person who posted or sent the message is reliable or not.

Do they have authority on the topic they are talking about? Are they involved in any official response groups? If the information came from a group, check if they are affiliated with the government or any authoritative private entity.

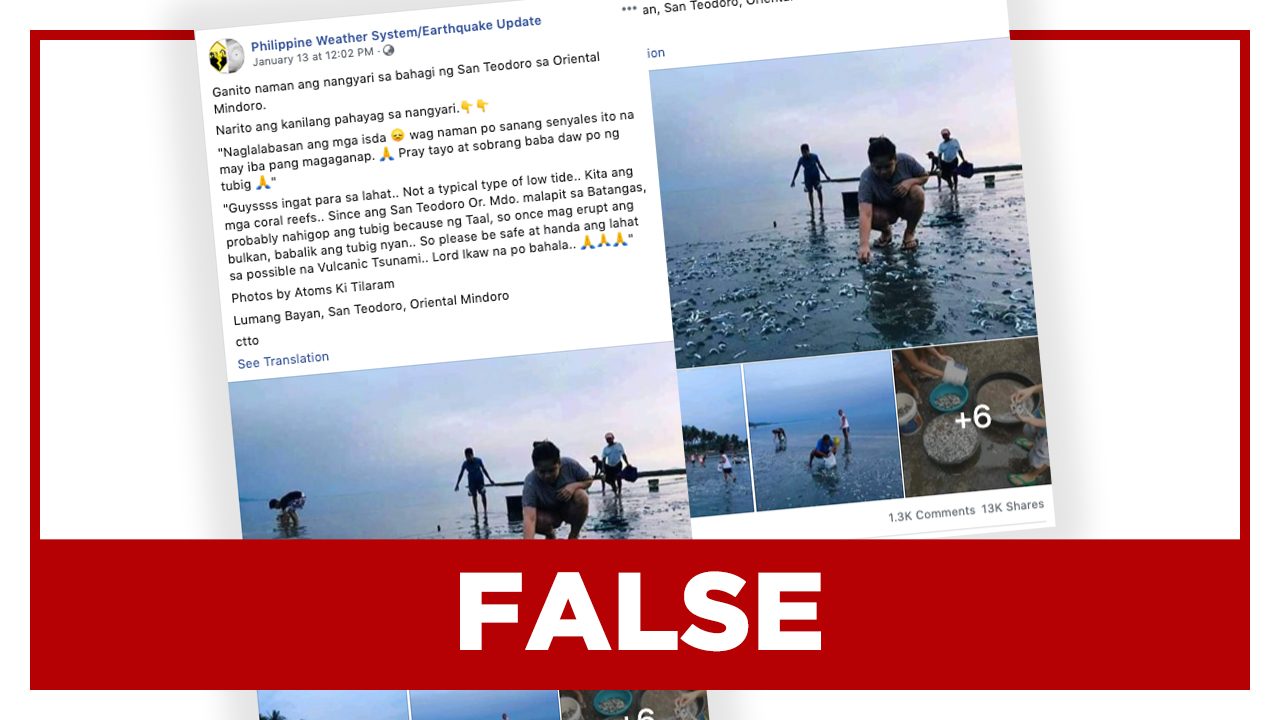

On January 16, Rappler debunked a claim that said the low tide in Oriental Mindoro is a sign of a possible volcanic tsunami. This came from Facebook page Philippine Weather System/Earthquake Update.

Although the name of the page sounds authoritative, it is not affiliated with any government agency. In fact, Phivolcs contradicted the claim made by the page by saying it is “almost unlikely” for the low tide in Oriental Mindoro to cause a volcanic tsunami.

It’s also worthwhile to check if the person or group that posted suspicious claims has shared other false posts before.

There are a lot more hoaxes and false information Rappler has debunked about the Taal eruption and 2019 novel coronavirus. If you continue to spot a particular claim going viral that is left unchecked, send a link and a screenshot to factcheck@rappler.com for verification. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.