SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

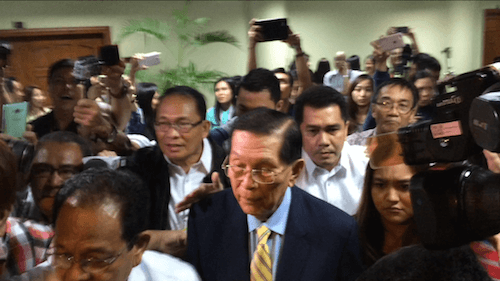

MANILA, Philippines – Former senator Juan Ponce Enrile said it himself: he’s a very experienced trial lawyer.

He said it while expressing confidence that all will work out in his favor and he would be cleared of all the charges in relation to the multi-billion peso Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) scam.

“Why should I get stressed out? I know myself. I know what we did. My office, I think, is blameless,” Enrile said two years ago.

So far, he has managed to convince the Supreme Court to grant him bail, while two of his co-accused, former senators Jinggoy Estrada and Bong Revilla, remain in detention at the Philippine National Police (PNP) Custodial Center. (READ: The triumph of Juan Ponce Enrile)

On Wednesday, February 1, the Sandiganbayan Special Third Division denied Enrile’s motion to quash, setting in motion the plunder charges filed against him for allegedly earning P172 million in kickbacks from his PDAF.

But it wasn’t without a good challenge from the the 93-year-old “legal rockstar” who has on his counsel team lawyers of his calibre, including veteran litigator Estelito Mendoza.

Here is how Enrile has so far been fighting his plunder charges:

First stop: Sandiganbayan for a bill of particulars

A bill of particulars simply means a detailed account of allegations. Enrile argued that for his team to craft a good defense, he must be provided with facts and circumstances alleged in the charge sheet.

For a public official to be guilty of plunder, it must be proven that he/she conspired with others to amass wealth amounting to at least P50 million through methods specifically provided for by the law. (READ: What’s the difference: Plunder, graft in PDAF issue?)

Enrile argued that the charge sheet provided by state prosecutors was “a bundle of confusing ambiguity.”

His lawyer Mendoza told Sandiganbayan justices during oral arguments that as in a game of poker, the prosecutors were merely bluffing and that the court just cannot allow them to win on a bluff.

Enrile said that to be able to proceed with the charges, prosecutors must be able to answer specific questions:

- “From whom and for what reason did he (Enrile) receive any money or property from the government through which he ‘unjustly enriched himself?'”

- “What was the overall plan? Who were parties to its conception? And to its implementation? When and how much did [Janet] Napoles misappropriate for her personal gain?”

- “Who paid the money? Who received the money? When was the money paid? Where was it paid?”

- “What COA [Commission on Audit] audits or field investigations were conducted which validated the findings that each of Enrile’s PDAF projects in the years 2004-2010 were ghosts or spurious projects?”

- “Who paid Napoles, from whom did Napoles collect the fund for the projects which turned out to be ghosts or fictitious? Who authorized the payments for each project?”

- What are each of the projects allegedly identified, how, and by whom was a project identified, the nature of each project, where it is located and the cost of each project?

On July 11, 2014, the Sandiganbayan denied this motion and proceeded to arraign Enrile. The former senator, still contesting the decision, refused to enter a plea.

Failing the Sandiganbayan, Enrile goes to the Supreme Court

Enrile petitioned the High Court to overturn the Sandiganbayan’s decision, and he won.

Voting 8-5, the SC granted Enrile’s petition, ordering the Ombudsman to provide the former senator with details on the following:

- The particular overt acts alleged to constitute the “combination or series of overt criminal acts”

- A breakdown of the amounts of commissions allegedly received, stating how the amount of P172,834,500 was arrived at

- A description of the “identified” projects where kickbacks were received

- The approximate dates of receipt, “in 2004 to 2010 or thereabout” of the alleged kickbacks from the identified projects

- Names of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) allegedly controlled by Janet Lim-Napoles, which were the alleged “recipients and/or target implementors” of Enrile’s pork barrel projects

- The government agencies where Enrile allegedly endorsed Napoles’ NGOs

The justices who voted in favor of Enrile’s petition were Justices Presbitero J. Velasco Jr, Teresita J. Leonardo-De Castro, Arturo D. Brion, Diosdado Peralta, Lucas Bersamin, Jose Perez, Jose Mendoza, and Estela M. Perlas-Bernabe.

Those who dissented were Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno, Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio, and Justices Mariano Del Castillo, Martin Villarama Jr, and Marvic Leonen.

Justice Bienvenido Reyes, who was on leave, took no part in the voting. Justice Francis Jardeleza inhibited because he handled the case when he was Solicitor General.

Petitions the SC to grant him bail for a non-bailable offense

The Sandiganbayan had already denied Enrile’s petition for bail, but he nonetheless took matters to the Supreme Court, arguing that the prosecutors never refuted his claim that he was not a flight risk.

He also said that the SC once allowed him to post bail in 1990 even when he was then charged with a capital offense – rebellion with murder and multiple frustrated murder.

The SC favored Enrile, citing humanitarian reasons. After paying a P1-million bail, Enrile walked free and was able to resume work at the Senate. Justice Marvic Leonen, among the 4 dissenters in the decision, said there is reason to believe that the favorable ruling was a case of political accommodation.

After wins before the Supreme Court, he files a motion to quash before the Sandiganbayan

Enrile’s motion shows his attention to detail, and sharpness reminiscent of the Corona trial in 2012 that earned him high trust and approval ratings. (READ: At 90, Enrile a bundle of contradictions)

Below are the major points Enrile raised in his motion, and how the Sandiganbayan ruled:

1. LACKING DETAILS

MOTION: Enrile noted a principle called “unjust enrichment” or increasing your wealth at the expense of others through unlawful means. Enrile said the bill of particulars does not prove he committed the crime of “unjust enrichment.”

Enrile said the SC clearly ordered the Ombudsman to say “how the kickback was received, when it was received and how much was received.” Instead, Enrile said prosecutors merely alleged that it was him who authorized his staff to sign documents for him, and that he wrote various letters to agencies.

DECISION: The Sandiganbayan said they have provided Enrile with dates of receipts of his kickbacks, answering the “when” and “how much”. However, the “how” question and a detailed description of the project where his PDAF went to are, according to court, “evidentiary matters” which will be provided during trial.

On the matter of unjust enrichment, the court said that the non-evidentiary details provided already prove that Enrile took advantage of his power and connections to unjustly enrich himself.

These “non-evidentiary details” include establishment of facts such as Enrile’s PDAF being coursed through Napoles NGOs, and Napoles giving Enrile, through his former chief of staff Gigi Reyes, a percentage or kickback.

“Informations need only state the ultimate facts; the reasons therefore could be proved during trial,” the anti-graft court’s resolution said.

2. NOT FROM PUBLIC FUNDS

MOTION: To be charged with plunder, the kickback must have come from public funds. Enrile argued that even if it is proven true that Napoles delivered money to him or Reyes, that money is not considered public funds. He said one kickback remittance worth P1.5 million was delivered to him even before he released his PDAF, meaning the money came not from his PDAF, but from Napoles’ private funds.

Enrile further cited one of the whistleblowers’ testimonies, saying the money given to him came from Napoles’ vault, meaning it was her own money if it came from her vault.

DECISION: The Sandiganbayan said the plunder law is not concerned with whether the money per se came from a public fund or not. They said the law just asks whether a kickback was earned from “a person or entity in connection with any government contract or project or by reason of the office or position of the public officer concerned.”

With regards to the vault, the anti-graft court said the testimony only supports the information filed that the “cost of a project to be funded from Enrile’s PDAF” will be the same amount of money to be paid as kickback “before, during and after the project identification.”

3. NO EVIDENCE OF HIM PERSONALLY RECEIVING MONEY

MOTION: Enrile cited Luy’s testimony where the whistleblower said he had not made or seen any delivery of money to Enrile, and that Enrile’s name also does not appear in his ledger. Even Ruby Tuason, who claimed she personally delivered money to Estrada, said she only dealt with Reyes.

Because of this, Enrile said there is no probable cause to charge him for plunder.

DECISION: The Sandiganbayan did not directly address Enrile’s argument that there was no evidence he received the money himself.

However, the court noted that when it denied Enrile’s motion for bill of particulars in 2014, they already ruled that there was probable cause.

But, the court said, Enrile did not challenge the findings before the Supreme Court. “What he filed with the Court was a motion for bail. In filing the motion for bail, accused Enrile effectively recognized the finding of probable cause by the court. Thus, he is now barred from raising this issue especially at this late day,” the resolution read.

4. THE ARROYO DOCTRINE

MOTION: Enrile allegedly earned P172 million in kickbacks. But, Enrile said, the charge sheet failed to identify who the “main plunderer” was and that it failed to specify just how much each of the 5 accused got in kickbacks.

Here he cited the SC’s acquittal of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo in her plunder case over the PCSO mess. In its decision then, the SC said that because there wasn’t a main plunderer, it can be presumed that all 10 accused got equal shares of the kickbacks.

So, Enrile said, if there were 5 of them and only P172 million, that would mean each one got only P34.4 million, which is below the P50-million threshold required to charge someone for plunder.

DECISION: The Sandiganbayan said that Enrile could not use the Arroyo decision.

The SC, in its acquittal of Arroyo, noted that the reason former president Joseph Estrada was convicted of plunder was because a “main plunderer” was identified, which was him.

In Estrada’s conviction, it was proven that the conspirators “helped the former President amass the ill-gotten wealth.” But the same thing could not be proven for Arroyo. And because there was no main plunderer in her case, the Pampanga congresswoman could not be charged. (READ: SC’s acquittal of Arroyo)

However, according to Sandiganbayan, the principle does not apply to Enrile because the SC “had already made a categorical pronouncement that the information validly charges the offense of plunder.”

The court said there is no longer a need to identify a main plunderer.

“The Supreme Court had already declared that since the Information in this case sufficiently alleges conspiracy, then it is unnecessary to specify, as an essential element of the offense, whether the ill-gotten wealth amounting to at least P172,834,500 had been acquired by one, by two or all of the accused,” the resolution read.

It added: “In the crime of plunder, the amount of ill-gotten wealth acquired by each accused in a conspiracy is immaterial for as long as the total amount amassed, acquired or accumulated is at least P50 million.”

Long road ahead

With this recent setback in their defense, Enrile is expected to fire more appeals and avail of all legal remedies using his and his team’s combined legal prowess.

The case is now set to undergo pre-trial, during which the Enrile camp could again file a motion to stop it from proceeding to trial.

Even when it does, the judicial system still allows for numerous opportunities for Enrile to get it dismissed. (READ: Plunder and graft trials: How do cases proceed in the courts?) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.