SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Ask any graduate of the education department’s Alternative Learning System (ALS) why they left formal school, and each would have a different story to tell.

Here is Maricel Pascua’s story.

On her second year of high school, Pascua had to stop attending her classes because her aunt could no longer fund her schooling. Sure, education is free in public high schools, but the cost of getting there is another matter. For Pascua, who takes 3 public rides to get to school, the transportation cost was an everyday expense she couldn’t afford.

Like what many out-of-school youth would do, Pascua looked for a job. Instead of burying her head in books, she spent the last of her teenage years at a furniture factory, and met a man whom she married when she was 19.

They had 3 kids, and for a time, Pascua’s life revolved around them. Years passed, and before she knew it, she was 27 years old and still not a high school graduate.

That was in 2007 – the year she learned about ALS.

“May mga nakapagpatunay na pasado na sila, so ‘ayun nag-aaral sila kahit medyo may edad na. Sabi ko, ‘Why not? Ako rin’ (There are people who passed the Accreditation and Equivalency Test, so they still studied even if they’re already old. I said, ‘Why not? I can do it too’),” Pascua shared.

So determined was Pascua to finish high school that she passed the ALS Accreditation and Equivalency Test (A&E) on her first take and after 10 months in the ALS program.

“Every time na makikita mo sila, paalalahanan mo, kasi one of these days, sa buhay nila, malalaman nila, ‘Ay oo nga, tama si Ma’am, na kailangan ko mag-aral, kailangan ko makatapos.”

– Maricel Pascual, ALS teacher

But she had bigger dreams for herself and she didn’t want to stop at a high school diploma. She applied at a local university in Taguig, passed the college entrance exam, and picked a course that, she said, “fits her age”: education.

She survived 4 years of college through sheer determination – she wanted to give her children a better life. Never mind that her husband wasn’t as supportive as she wanted him to be; she managed to stay in school by working extra jobs on the side.

“Ang daming nangyari sa buhay ko bago ako nakagraduate ng college. Habang nag-aaral ako, ‘yung mga anak mo nag-aaral din, tapos naglalabada, nangangatulong sa kapitbahay, pati pangagalakal ginawa ko ‘yun kasi ‘yung asawa ko hindi rin siya tapos,” Pascua said, turning emotional as she recounted her experience.

(A lot of things happened in my life before I was able to graduate from college. While I was studying, my children were studying too, and I had to do others’ laundry, I became a neighbor’s house help, and I even did scavenging since my husband did not finish high school, too.)

“Hindi ako nahihiya [na mangalakal ng plastik, bote] kasi pamilyadong tao na ako e. Kahit saan ako mapapunta, pupulutin ko talaga siya para ipunin. O minsan, bitbit ko pa ‘yung bunso ko para mangalakal talaga.”

(I’m not ashamed of scavenging for plastic and bottles because I have a family. Everywhere I go, I’d pick up stuff so I could gather them. Or sometimes, I even brought my youngest child with me during scavenging.)

Returning the favor

All that hard work paid off because Pascua not only finished college, she also passed the Licensure Examination for Teachers on her first take. Now she’s teaching first graders on weekdays, and ALS students on Saturdays.

“Nagturo ako ng ALS dito parang to pay back. Parang ano ka, tumatanaw ka ng utang na loob (I’m teaching ALS here to pay back, pay a debt of gratitude),” the 37-year-old ALS instructional manager (IM) said.

Pascua continues to teach ALS even if the program she was with – the Aquino administration’s Abot-Alam Program – had been discontinued.

ALS itself faced quite a few challenges during the last administration.

Aside from a 2016 Commission on Audit report calling out the Department of Education (DepEd) for its failure to spend P2.92 billion or 90% of its budget for the Abot-Alam Program, DepEd’s Bureau of Alternative Learning System was also abolished following the department’s rationalization plan.

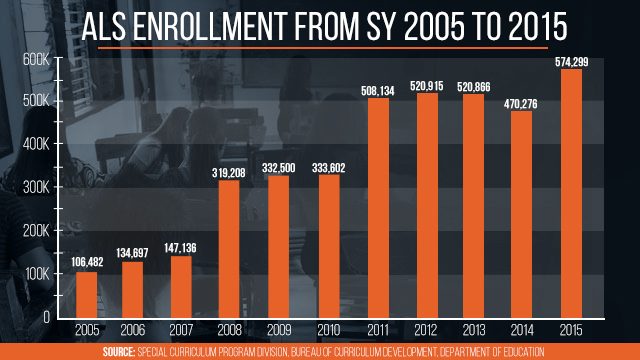

But there were gains as well. Based on DepEd’s Transition Report 2010-2016, enrollment in ALS has grown steadily in recent years, with enrollment hitting 574,299 as of 2015. The report said the rise in enrollment figures indicates increasing public awareness and demand for the program.

It is estimated that the current enrollment is “only 10% of the size of the potential target ALS learners.” A 2016 World Bank report on ALS said the realistic size of ALS target population should be around 5.4 million people.

“Saan nanggagaling itong mga out-of-school youth? Hindi sila maubos-ubos,” Pascua observed. “[Pero] limitado ang mobile teachers sa every division. Kaya ‘yung pananaw ko, kung every barangay mayroong isang mobile teacher, ‘yun lang gagalugarin niya, hahanapin niya talaga, mauubos ‘yan.“

(Where are all these out-of-school youth coming from? They keep coming. But the mobile teachers are only limited in every division. That’s why in my view, if every barangay has a mobile teacher, and he or she really looks for these out-of-school youth, there won’t be any more of them eventually.)

Education Assistant Secretary for ALS G.H. Ambat agreed, saying the ideal ratio is one ALS teacher per barangay.

Teaching ALS

Pascua is just one of two ALS teachers in Upper Bicutan Elementary School, and one of over 70 IMs in Taguig City. These IMs are only contracted by DepEd because the number of DepEd-delivered mobile teachers are not enough to serve the city’s yearly average of over 1,000 ALS learners.

According to District ALS Coordinator Frumence Hermoso, Taguig currently has only 4 mobile teachers. Unlike Pascua who also teaches students in formal school, mobile teachers work full time to map the out-of-school youth in the community and introduce them to ALS.

“You can either go house-to-house, which sometimes we really do, and we talk to people who are probably purok (zone) leaders and so on to invite others, or minsan nadaanan lang namin, nagtutulak ng kariton (or sometimes we pass by them, those who push carts) we invite them to join the ALS,” Hermoso explained.

With only 4 mobile teachers for all of Taguig’s 28 barangays, the work is cut out for them. Pascua said she would go full time in ALS if only she were still single and not the breadwinner.

“Enjoy rin akong may regular [class], kumbaga pamilyado kasi ako e, so ‘yung benepisyo na nakukuha ko sa regular, parang mas gusto ko ‘to. Pero kung…siguro single ako, e-enjoyin ko ang pagiging mobile teacher,” she explained.

(I enjoy my regular class because I have a family, so the benefits that I get from teaching regular classes, I think I like it better. But maybe if I were single, I’d enjoy being a mobile teacher.)

In an interview with Rappler, Ambat said there are currently 7,364 learning facilitators in the country. About 2,813 are mobile teachers and district ALS coordinators like Hermoso – DepEd-delivered facilitators who have permanent positions at the department.

But the same World Bank report found that while DepEd-delivered learning facilitators are paid more than DepEd-procured learning facilitators like Pascua, there is “no clear difference in work efficiency” between the two groups.

“Currently, DepEd-procured learning facilitators are paid substantially less than DepEd-delivered learning facilitators, regardless of individual effort and performance. However, DepEd-delivered facilitators have more teaching experience than procured facilitators, which generally improves teaching effectiveness and performance,” the report said.

“Introducing performance-based payment, particularly to DepEd-procured facilitators, may create effective work incentives and improve learning outcomes.”

But for Pascua, mobile teachers still deserve better benefits. Hermoso agreed, “Siguro wish list ko sa area ng mga teachers, sana nga maincrease-an lalo [ang] sahod (Maybe my wish list in the area of teachers, I hope they get a salary increase.)”

Passing the A&E

Not everyone who enters ALS leaves the program with a high school diploma.

DepEd said in its 2016 transition report that out of the 2,740,144 who have completed the 10-month A&E program since 2005, only 1,386,556 took the actual examination, while only 461,748 passed it.

“The most common reason for discontinuance was that they decided to work,” the transition report said. Pascua knows this by experience.

“‘Yung mga estudyante kong ALS na hindi nagpatuloy, ‘pag nakikita nila ako sa labas, nagmamano. ‘O, bakit ‘di ka nagpatuloy?’ ‘E Ma’am, ano e, nagta-trabaho ako e’,” she recalled them as saying.

(My ALS students who did not continue, when I see them outside, they’d kiss my hand. I’d say ‘Why didn’t you continue?’ and they’d reply ‘Ma’am, I’m working already.’)

She would tirelessly remind them that there are better opportunities for those who finish school.

“Every time na makikita mo sila, paalalahanan mo, kasi one of these days, sa buhay nila, malalaman nila, ‘Ay oo nga, tama si Ma’am, na kailangan ko mag-aral, kailangan ko makatapos.'”

(Every time you see them, remind them, because one of these days, in their life they will realize, ‘Ah, Ma’am was right, I really need to study, I really need to finish school.’)

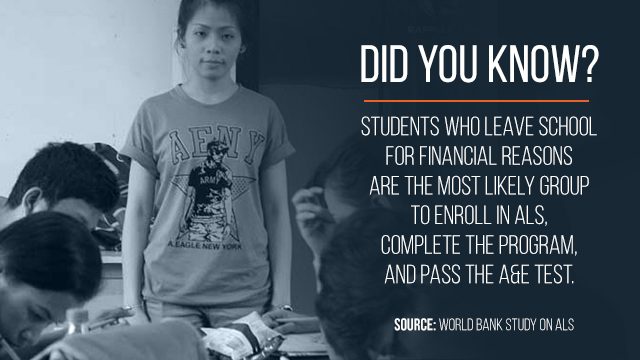

DepEd said future interventions need to target lowering economic or sociological opportunity costs for ALS learners to improve the program’s enrollment and completion rates.

This is important because as the World Bank report shows, higher income is attained only when an ALS learner passes the A&E.

Expansion?

During her early months in office, Education Secretary Leonor Briones said ALS will be the “centerpiece” of the Duterte administration that will complement the K to 12 program.

Duterte himself mentioned ALS in one of the only two lines in his State of the Nation Address on basic education: “We will also intensify and expand Alternative Learning System programs.”

But the World Bank, in its report, gave a fair warning about expanding ALS.

“Given the magnitude of the ALS target youth (ranging between 5 and 6 million), an expansion of ALS programs is needed to offer a second chance to those who did not start school or failed to complete it. The study accepts that an expansion of the program may not be an ideal solution, since the expansion itself may distort incentives among students currently in school,” the report read.

Authors of the report worry that students in formal school who are “at high risk of dropping out” might “see ALS as an easy path to a diploma.”

“Therefore its expansion would have the unintended consequence of increasing the dropout rate. However, we believe that students who were deprived of basic education opportunities for any reason including conflicts and violence deserve a second chance and that ALS is their best hope for continuing and completing their schooling.”

So how exactly will the Duterte administration expand ALS? At least for 2017, Briones said DepEd has an “intense catching up” to do. (To be concluded) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.