SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – With President Rodrigo Duterte’s declaration of martial law in Mindanao, all eyes are now on Congress, authorized by the 1987 Constitution to review the proclamation.

Article 7, Section 18 requires the President to submit a report within 48 hours of declaration to Congress, which has the power to either revoke or extend it through joint voting.

But unlike in 2009, when Congress deliberated on then president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s proclamation of martial law, the Senate and the House of Representatives are now lukewarm to the idea of convening both chambers. Not necessary, not required, no opposition, they said.

In December 2009, a joint public session was convened at least thrice after Arroyo, who was then suffering from negative public ratings, declared martial law in Maguindano following the Maguindanao massacre.

The marathon deliberations, lasting several hours, were dominated by questions from opposition lawmakers against the proclamation.

But now, Congress, filled with administration allies, is so far keen on virtually letting the popular president off the hook with his Proclamation No. 216, declaring martial law and suspending the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus in Mindanao after government clashes with the Maute Group in Marawi City.

Congress leaders even said it is “unlikely” for Congress to revoke Duterte’s proclamation.

“Why would they want a joint session when it is not necessary, not needed, not really called for? It’s not necessary at all except [for] media mileage,” said Senate Majority Leader Vicente Sotto III in a text message to Rappler.

House Speaker Pantaleon Alvarez and Majority Leader Rodolfo Fariñas earlier said there won’t be any joint session to discuss the proclamation.

“Natanggap po namin yung written report ng ating Pangulo kagabi. Wala po kaming gagawin na pag-convene ng Kongreso pero bibigyan ng kopya ang bawa’t miyembro (We already received the written report of the President last night. We won’t convene Congress but we will give each member a copy),“ Alvarez said in an interview on ANC.

Malacañang submitted its report to Congress on Thursday night, May 25. The report details Duterte’s grounds for his declaration, citing threats from the terrorist group Islamic State (ISIS). (LOOK: Duterte’s report to Congress on martial law)

In lieu of a joint public session, the Senate and the House of Representatives are eyeing separate closed-door briefings on Monday, May 29, with national security officials.

2009 v 2017: What’s the difference?

Following the massacre of 57 people in Maguindanao led by the powerful Ampatuan clan, Arroyo placed Maguindanao under martial law in December 2009.

She also suspended the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus in the province except “for certain areas”, thus enabling the military to make arrests without court intervention.

It was the first declaration of martial law in the country since 1972 under dictator Ferdinand Marcos. It was also the first covered by the 1987 Constitution, which was crafted precisely to prevent grave abuse and prevent another Marcos from tinkering with civil rights.

The 1987 Philippine Constitution says that the President, as commander-in-chief, may “in case of invasion or rebellion, when the public safety requires it” suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus or place the country under martial law. The writ safeguards individuals against arbitrary arrest.

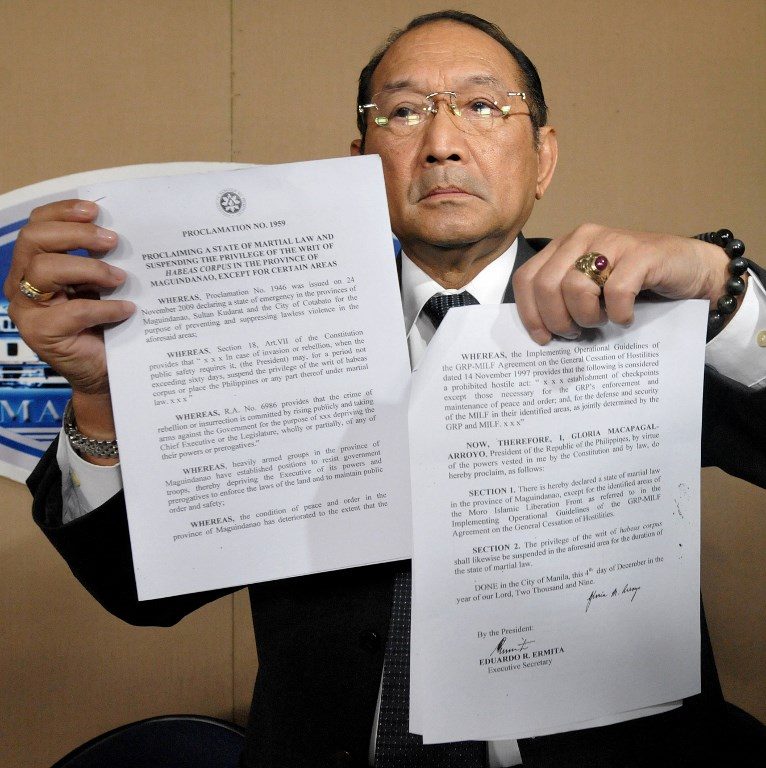

Arroyo’s Proclamation No. 1959 was meant to deal with the reported rebellion of forces loyal to the Ampatuan family after its members were implicated in the massacre.

Arroyo lifted the declaration after only 8 days, before Congress – then with a mounting opposition to her – scheduled the vote on the matter.

At the time, Arroyo’s trust and satisfaction ratings were at an all-time low (-38 net satisfaction rating), as her administration was hounded with legitimacy and corruption issues. She was even the “most distrusted” government official then, according to surveys.

The proclamation and deliberation also happened a few months before the May 2010 presidential elections, with some lawmakers eyeing reelection or other posts.

In Duterte’s case, his declaration coincided with his high popularity and satisfaction ratings.

Asked why the change in Congress’ move, Sotto, Duterte’s ally, said the conditions under the Arroyo and Duterte administrations are different.

“The threat during GMA’s time could have been addressed surgically while the threat today could have national and international implications if not addressed with decisiveness and strong will,” Sotto said.

“The Maute Group could be associated with ISIS and that is the last thing we would want to happen to our country. Those opposing should realize that there are enough safeguards in the Constitution available to us in case of abuse,” he added.

But with Duterte’s repeated mention of martial law even before his actual proclamation and his supposed human rights record, some have raised concerns about possible abuses. (READ: Ramos fears ‘more harmful’ martial law under Duterte)

“The Constitution provides for transparency, accountability, as well as the right of the citizen to information of public interest. And obviously, all these 3 are necessary, especially the declaration of martial law is a serious matter. Millions are affected because the declaration is for the whole Mindanao,” said minority Senator Francis Pangilinan, Liberal Party president, in a mix of Filipino and English.

Pangilinan, also a senator in 2009, recalled that the Senate then, filled with Arroyo critics, passed a resolution with at least 17 senators calling for a joint session.

Shielding a popular president?

But times now seem to have changed. Under the Arroyo administration, Congress had the advantage over her, according to political analyst Aries Arugay.

After all, it was Congress that “helped Arroyo become president” despite issues against her administration following the “Hello Garci” scandal. Arroyo also had to “keep the wheels of patronage well-oiled” at the time because of impeachment threats against her.

“In 2009, Congress had the upper hand since GMA was suffering a legitimacy deficit,” Arugay told Rappler in an interview.

On the other hand, Duterte became president despite the absence of Congress’ support. This fact is not lost on the Chief Executive himself after he told lawmakers in his first State of the Nation Address that he owes them nothing because they supported other bets in the 2016 polls.

Congress at present, Arugay said, serves as the “protector” of the President, who still enjoys wide public support. Convening Congress, in short, would “expose” the President to scrutiny.

“Congress under Duterte is acting more like a legislative shield. Instead of checking executive power, the legislature protects the president from existential threats,” Arugay said.

“The President still is very popular and still has budgetary powers, not to mention the patronage resources from PDP-Laban,” he added, referring to Duterte’s party, whose membership has ballooned since he took office.

With a popular president, a politician faces the risk of a backlash if he goes a different path.

“Duterte can say they are preventing him from doing his job. It will appear that they are against security and order. Do you really think Congress wants to be painted as preventing actions against terrorists?” Arugay said.

“On matters of national security, politics stops at the water’s edge. This age-old adage is more relevant under a Duterte presideny who is fighting wars in multiple fronts,” he added, referring to lawmakers’ aim for survival.

After all, the present choices of lawmakers might haunt them soon, or in two years, during the 2019 midterm elections. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.