SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – In the past year, President Rodrigo Duterte’s administration has stayed true to its promise of giving attention to the needs of overseas Filipino workers (OFWs).

Thousands of stranded OFWs were sent home through the amnesty granted by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Philippine government’s own efforts to repatriate workers.

The Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE), together with the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA), has set up a one-stop shop where aspiring migrant workers are able to swiftly process their applications.

Albeit there was lack of clear guidelines, the DOLE also launched the OFW ID that will replace the overseas employment certificate (OEC). There’s also the OFW bank, which is set to open in the latter part of 2017.

But aside from all these, Duterte has one big goal for the country’s migrant workers. (READ: How Duterte gov’t cared for OFWs in first 100 days)

“Final goal ng ating Presidente (The final goal of our President) is get them all back by providing good jobs with pay,” Labor Secretary Silvestre Bello III said in early July.

Here’s how the government plans to bring OFWs back home.

Dutertenomics to generate jobs

To bring them home means to provide them jobs that would earn them enough to sustain their families’ needs.

The labor department is banking on Dutertenomics, the heart of the Philippine Development Plan, that aims to generate two million jobs per year or some 10 million jobs by the end of Duterte’s term in 2022.

What kinds of jobs will be created? Economic managers said immediate employment opportunities would be in the field of manufacturing and construction since there will be massive projects in the so-called golden age of infrastructure. (READ: For Dutertenomics to work, the President has to take charge)

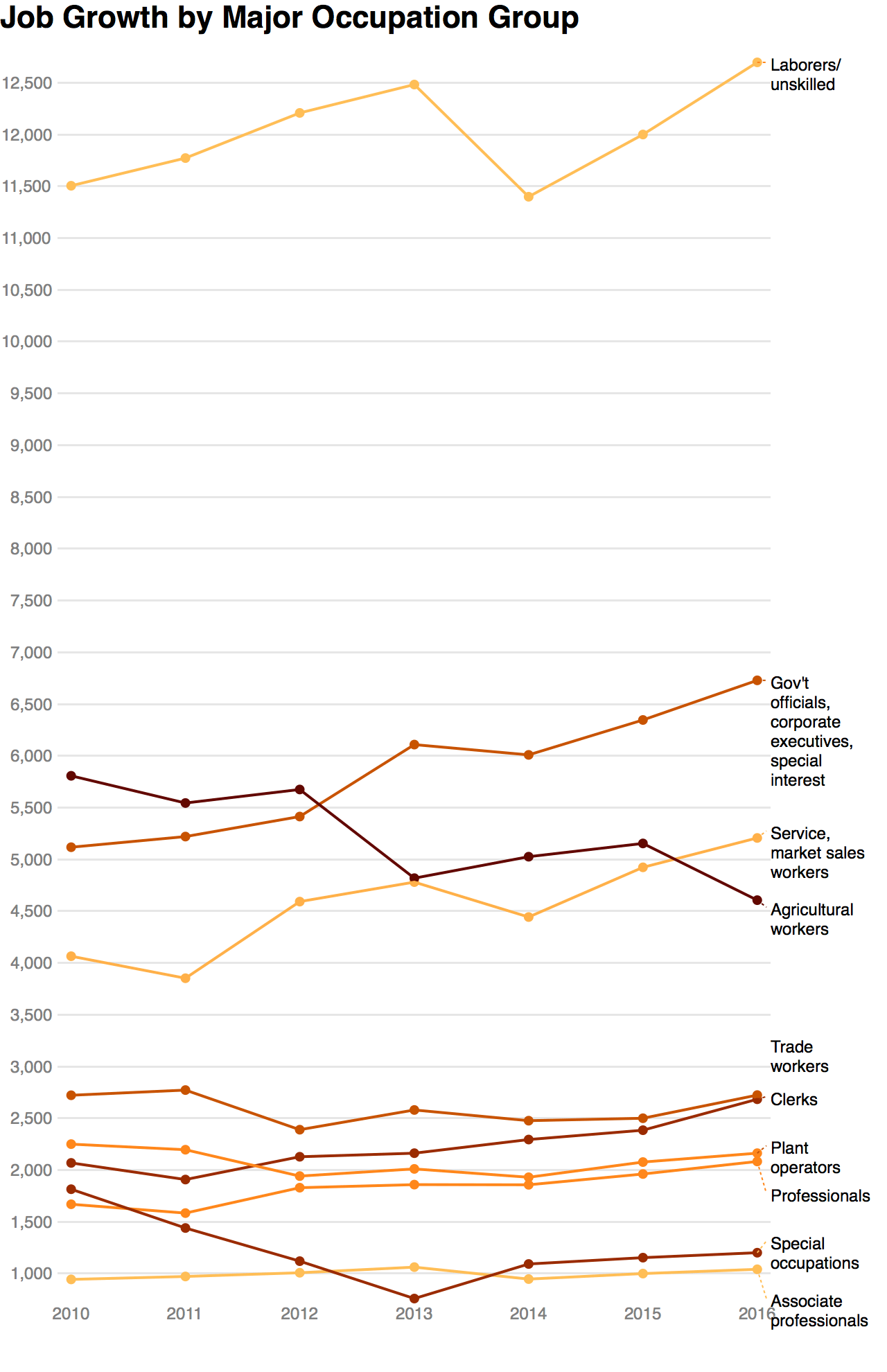

Based on data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), the following job classifications saw the highest increase during the past administration:

- Laborers and unskilled workers

- Trade and related workers

- Plant and machine operators

- Technicians and associate professionals

Most jobs were generated for those in the construction sector and fit for low-skilled individuals. These types of employment also have the lowest daily wage rate. Based on the latest available data, a worker in this group earns P5,387.76 a month, provided an individual works for a maximum of 6 days in a week.

Most jobs were generated for those in the construction sector and fit for low-skilled individuals. These types of employment also have the lowest daily wage rate. Based on the latest available data, a worker in this group earns P5,387.76 a month, provided an individual works for a maximum of 6 days in a week.

Except for technicians and associate professionals, the other jobs generated in the last years are also covered by the minimum wage.

Development think tank Ibon Foundation observed that “poor quality of work persisted” under Duterte’s first year in office. It cited the significant drop in the labor force participation (LPFR) as the President approached his first year in office. This was despite the lower unemployment and underemployment rates recorded in April 2017.

“LPFR fell to 61.46%, which is the lowest in 36 years since the country’s severe economic crisis in 1982 under the Marcos dictatorship. This implies that the labor force shrunk by 575,000 in April 2016 despite the 1.4 million increase in the [working] population,” Ibon explained in a published feature.

“This is most likely due to the ever-growing numbers of discouraged workers dropping out of the labor force after failing to find jobs,” it added.

This kind of employment status won’t be attractive enough to entice OFWs to return home. But since infrastructure spending is linked to development, this may pave the way for the country to reach a “migration hump” that will shift the gears of labor-sending.

Labor expert Rene Ofreneo explained migration hump as a development level that shifts a country from a labor-receiving status to a labor-sending one, just like what happened in Japan and South Korea.

“South Korea was poorer than the Philippines in the 1960s. But then President Park-Chung hee modernized and industrialized the country. He imprisoned businessmen until they came up with an industrial vision for South Korea,” said Ofreneo in a mix of English and Filipino.

“There is an increasing number of OFWs who prefer to go home but we still can’t say it’s a hump,” he added.

Reintegration programs

While the nature of jobs under Dutertenomics remains prospective, the government will also have to look into other aspects of welcoming the OFWs back.

The government is looking at improving the existing reintegration programs for returning migrant workers. These include employment and livelihood training, and OFWs’ access to credit, and grant money to start their own business.

The Overseas Workers’ Welfare Administration (OWWA) has increased the grant awarded to beneficiaries of their Balik Pilipinas, Balik Hanap Buhay Program from P10,000 to P20,000.

It also has the Entrepreneurial and Development Livelihood Program with Landbank. It provides P100,000 to P2 million loan with collateral requirement for those who want to establish businesses.

Another program they are studying is the establishment of a micro-lending program for a minimum amount of P50,000 to as much as P300,000 minus the collateral requirement.

Meanwhile, the National Reintegration Center for OFWs (NRCO) is boosting efforts to provide jobs to teachers who chose to work as domestic helpers abroad. DOLE and the Department of Education have signed a memorandum of agreement to accommodate returning OFWs in the vacant teaching positions through the program Sa Pilipinas Ikaw Ma’am, Sir (SPIMS).

So far, around 600 OFWs have been hired and 2,000 have applied since 2016.

The positive effects of these government programs have yet to be seen, says Dr Maria Elissa Lao of the Ateneo de Manila University.

In her policy paper “Managing Return: A Brief Policy Appraisal of the Philippine Overseas Employment Experience,” Lao points out that there is a need for tighter coordination among the agencies concerned with aiding returning migrants. Right now, these agencies – the OWWA, the NRCO, and the Commission on Filipinos Overseas (CFO) – are doing efforts separately.

“The government already has a set of institutions around return and reintegration. However, these efforts seem to lack the coherence and synergy in addressing the complex nature of the return and reintegration experience,” Lao wrote.

OWWA and NRCO are relying on the amended OWWA law to address this issue. Under Republic Act 10801 or the “Overseas Workers Welfare Administration Act,” the NRCO has been attached to the OWWA.

“With the attachment of the NRCO to OWWA, we are expecting a budget boost since 10% of OWWA collections must go to reintegration. We estimate that to be between P150-200 million,” said Director Jeffrey Cortazar of OWWA.

In the long run, he said they plan to map the skills of the OFWs when they are abroad so that they will have a database of their capacities, their plans when they go home, and the livelihood they prefer.

Cortazar said that from having a reactionary approach to reintegration, they plan to promote migration and development by providing options for OFWs to stay in the country.

“Our orientation has always been a reaction to crisis [like] wars in Libya, Iraq…. But we are shifting towards migration and development,” he said.

“This is the voluntary return. Meaning, planned and not resulting from a disaster or an emergency abroad. They return prepared to reintegrate with families,” he added.

Department for OFWs

One of the President’s promises to the OFWs is the establishment of a Department for OFWs or a Department on Migration and Development. It was among the requests Filipinos in Saudi Arabia told Duterte personally when he visited them.

Measures related to this are pending before the respective committees in the Senate and the House of Representatives. But analysts do not see this complementing with the promise to bring OFWs home.

The Center for Migrant Advocacy-Philippines and the Ateneo de Manila University’s Working Group on Migration, warned that it would institutionalize a labor-sending policy. This is contrary to the concept of migration and development that workers should be free to move out of personal preference and not economic needs.

Even Bello himself is not too keen on the proposal.

The labor secretary has mentioned that establishing a new agency does not go with the administration’s vision of streamlining the bloated bureacracy. Last July 26, the House of Representatives passed the measure on government rightsizing on 3rd and final reading.

Public administration expert Edna Co of the UP Center for Integrative and Development Studies said that setting up this new department might create more problems than solutions.

“We have many agencies on top of [POEA and OWWA]. We also have many non-governmental organizations that are really involved in issues of migration and OFWs,” she said in Filipino.

She also said the proposed department will only cater to a certain portion of Filipino migrants.

“There are different kinds of migrants. There are the OFWs who are low- or medium-skilled finding work. [But] we also have white collar workers who are not necessarily OFWs who left but will come back eventually. Some of them are permanent residents in other countries,” she said.

“You have to make your existing bureacuracy work because creating a new agency would not resolve the problem. There are a lot of red tape, a lot of procedure OFWs go through. What should be done is shorten the process,” she added. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.