SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Aena Briones was a grade school student when she was told to scour hospitals and look for blood. Her grandmother had been rushed to a hospital in Quezon City, a wound in her stomach, and needed blood badly. At the time, Aena was the only one in Metro Manila who could tend to her grandmother.

She remembers feeling out of her depth: a young girl going around from hospital to hospital, asking if they had blood units available, and walking away empty-handed. It wasn’t until she finally called her mother that they were able to find what they needed at a blood bank of the Philippine Red Cross (PRC).

Fast forward several years later, and Aena – remembering what she had to go through to help her grandmother – is now involved in Dugong Bayani, an online initiative that helps connect blood donors with patients who need them.

It was also by going online that Lish Mendoza was able to find blood donors for her sick father. In October last year, her family found out that her father’s bone marrow could no longer produce enough blood cells, and he was in urgent need of blood every two weeks.

Lish – who also regularly donated blood – found herself having to look for at least 6 volunteers to provide AB+ blood that her father needed.

So she turned to Facebook. Her name and face reappeared every so often on Facebook groups for blood donors and patients, as she appealed for kind-hearted strangers to spare a few hours of their day, come to the UST Hospital in Sampaloc, Manila, and help save her father’s life.

While there are blood banks in hospitals and centers like the PRC, the country’s blood supply still falls short of the target – which means that desperate patients may find themselves going from blood bank to blood bank, and not finding enough stock for their much-needed transfusions.

Because of this, people like Aena and Lish are turning to online networks in a bid to connect directly to those who can help.

Help from good Samaritans

Because her father needed several bags of blood at least twice a month, Lish found it difficult to find enough volunteers who were not only willing to go all the way to the hospital to donate, but also met the requirements for donating blood.

She posts frequently in a Facebook group calling for volunteers, and already lists down the hospital’s guidelines for potential donors – she’s had some instances where volunteers who responded to her call were turned away because they didn’t meet the requirements for donating blood.

Some of those who responded to her call even came all the way from Bulacan and Las Piñas just to donate.

“Some of them even call just to refer me to other organizations or people who can help. At least 4 people have done this for me,” she said.

Still, she’s had to beat the clock several times just to collect the required number of blood units for her father’s transfusion.

“I went to the Port Area at midnight, so I could look for blood. I got back to the UST Hospital at 2 am. The transfusion was set at 8 am,” she recalled.

Recalling her own difficulty in finding blood for her grandmother, Aena and other members of the University of the Philippines Red Cross Youth thought to link up potential blood donors with patients through Dugong Bayani.

The group initially began through the university network, coordinating student donors’ free time and linking them up with patients confined in nearby hospitals.

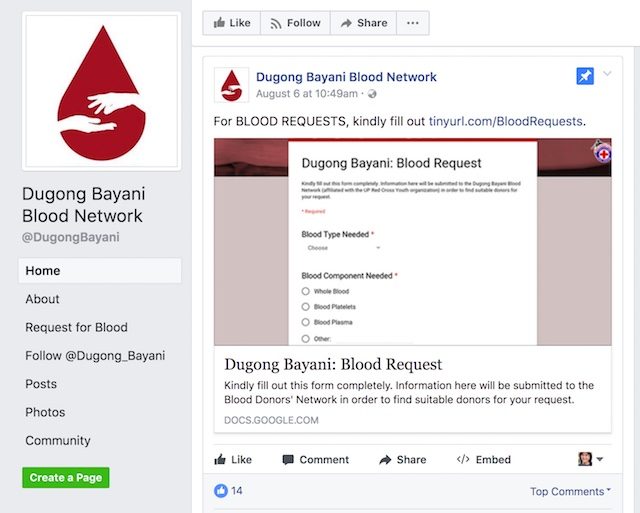

It now has its own Facebook page, where those who need blood fill out a form with details such as the blood type and component needed, the patient’s medical condition, and the hospital where the patient is confined.

Dugong Bayani posts this information online, allowing donors to contact the patients directly.

Below target

Aside from linking up directly with blood donors, one other way of getting blood is through the PRC, which provides nearly half of the Philippines’ blood needs.

Last year, the PRC provided 407,000 units of blood – nearly half of the 920,000 blood units collected by blood centers nationwide, according to the Department of Health (DOH).

Despite this, the country’s blood supply is still below target.

For a country to have adequate blood supply, the World Health Organization (WHO) says 1% of the total population must donate blood each year.

In recent years, however, the Philippines has still been falling short: in 2015, a total of 770,000 blood units were collected, and last year, that figure increased to 920,000.

For 2017, at least 1.03 million people – 1% of the 103 million population – should donate blood to reach the target.

“One percent of the total population must donate for the country to have sufficient blood supply. But because we don’t meet this, there’s the chance that some may die because they are not given blood,” Hanzel Sentones, donor recruitment head of the PRC National Blood Services, said in a mix of English and Filipino.

The PRC, the DOH, and other organizations around the country regularly conduct blood drives, but with the sheer number of people requesting for blood, it’s hard to keep up with the nationwide demand. On any given day, more than 2,000 blood units are used for transfusions throughout the country.

It’s also more challenging when the lean months roll in.

For the PRC, fewer donors come in around December, January, and the summer months from March to May.

Most donors come in during August, September, October, and February, when blood drives are plenty. Every day, though, the PRC has not been wanting of clients needing blood.

“And because we don’t meet the WHO’s target, we see on the ground how high the demand is,” Sentones said.

Since the start of the year, Sentones said the PRC has helped 140,000 patients with more than 200,000 blood units. Out of the 140,000, 20,000 are indigent and charity patients.

It’s not only the PRC and its 84 blood service units that provide blood to those who need it. Ideally, hospitals should have adequate stock in their own in-house blood banks. But when these run out, clients have the option of going to the PRC, submitting a blood request form, and bringing the blood back to the hospital – as what Aena did for her grandmother.

The PRC also has partnerships with several hospitals, providing them some of their blood stocks aside from servicing walk-in clients.

Process of donation

The PRC’s blood supply relies on free and voluntary blood donations. Soliciting payment for blood is illegal, based on Republic Act 7719 or the National Blood Services Act.

The blood donation process takes around 30 minutes. Donors fill out a questionnaire detailing their medical history. They will be interviewed and assessed by doctors to check whether they meet the requirements for donating blood.

These may vary among blood centers – some hospitals can have stricter guidelines – but according to the PRC’s basic requirements, blood donors should:

- be in good health

- between 16 and 65 years old (those aged 16 and 17 need parental consent)

- weigh at least 110 pounds

- have a blood pressure between 90 and 160 mmHg (systolic), 60 and 100 mmHg (diastolic)

- pass the physical and health history assessments

After this, the extraction process begins. The donor will then be allowed to rest for several minutes and given refreshments.

Every time someone donates blood, the PRC conducts screening processes to make sure the donated blood is safe for transfusion and free from transfusion transmissible infections, such as HIV, malaria, syphilis, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C.

Donors also get a blood donor’s card from the PRC that not only serves as a record of donation, but also gives priority to the donor when he or she is in need of blood.

But while donating blood is free, there is a fee charged from those who request for blood to cover the costs of screening and processing.

Based on RA 7719, blood centers can charge service fees for the collection and processing of donated blood.

“Since the PRC is not funded by the government, we charge a processing fee. We are just asking a fee for the processing. We use resources, manpower, blood bags, equipment, reagents, and that’s what people pay for when they pay the fee,” Sentones said.

The fees charged by the PRC depend on the kind of blood component needed by the patient: P1,800 for whole blood, P1,500 for packed red blood cells, and P1,000 for platelets and plasma.

Those who cannot afford the fees can have them waived with an endorsement from the hospital’s social worker. The PRC also runs a Blood Samaritan program – donations coursed through this program are used to pay for the blood processing fees availed by indigent patients.

In Lish’s experience, the frequent blood needs of her sick father – around 6 bags every two weeks – meant shelling out around P12,000 every month.

But what adds to the expenses are additional processing fees charged by the hospital where her father is confined.

Every time Lish gets blood from other blood banks or from the PRC, she would have to pay additional fees at her father’s hospital, which screens the acquired blood before it can be used for the transfusions.

It’s double the expense, Lish said. Why does blood from the PRC – which has already been screened prior to storage in the blood bank – have to be retested again when brought to a different medical facility?

Sentones said this is one of the issues encountered by clients.

“Kawawa naman ‘yung patients kasi they have paid for the processing fee sa Red Cross, so we assured them na it’s free from any transmissible infection. Pagdating sa ospital, pagte-test ulit. So ‘yung mga kliyente natin especially those who cannot afford multiple processing fees, magrereklamo. Tested na ng Red Cross ‘yan, ite-test ‘nyo pa ulit?” Sentones said.

(It’s unfortunate for the patients, because they have paid for the processing fee at the Red Cross, so we assured them that it’s free from any transmissible infection. And then when they get to the hospital, it’s going to be retested. So our clients, especially those who cannot afford multiple processing fees, they complain. It’s already been tested by the Red Cross, and it’ll be tested again?)

Sentones also said some hospitals have a policy of only accepting donors who go straight to the hospital, and don’t accept blood units from the PRC or from other blood centers.

“Maybe it’s part of their protocol or they have specifications. Some patients are more sensitive, especially if the shelf life of the blood has already been too long. There are doctors who want blood extracted within 3 days… There are those instances,” he said.

A human face to the statistics

This is why people like Lish prefer to look for donors themselves – it saves them additional expenses.

While online groups like Dugong Bayani help make the search process easier, it also has another aim: to promote its advocacy of getting people to donate blood.

To do this, its approach is a little more personal – most donors actually get to meet the patients whose lives they will be saving.

By forging that personal connection, Aena said this can encourage them to keep donating blood, since they will now see the human side of the problem and not just mere statistics.

She recalled how some patients’ relatives asked them why they were making the effort to come all the way to the hospitals and personally meet the patients.

“Ang sabi nila, ang hassle ng ginagawa ninyo…but the donors need to see what’s happening on the ground. Kailangan nila makita ang impact – feeling ko do’n nagla-lack,” Aena said.

(They said, what we’re doing seems to be a hassle for us…but the donors need to see what’s happening on the ground. They need to see the impact, and that’s where I think the blood advocacy is lacking.)

One of her most memorable encounters was accompanying a friend who donated blood for a patient who had a problem with her kidneys.

“When we entered the ward, we were met with applause, and the grandmother led everyone in singing a thank you song. She was very grateful that a stranger helped them. I think we were the last people they were waiting for to complete the needed blood bags,” Aena recalled.

For the PRC, getting Filipinos to understand the importance of donating blood is still a challenge.

Sentones said that if Filipinos only understood how very much needed their blood was, it would be easier for the country to reach the blood supply target.

Filipinos may not realize it, he said, but their blood can reach the farthest parts of the Philippines, helping save lives in far-flung provinces.

For Aena, what’s lacking in current initiatives to encourage blood donation is attaching a human face to the problem.

“Kapag nag-invite ako mag-donate, nakaka-disappoint ‘yung sagot na, ‘I never thought about it.’ Hindi alam ng mga tao ang pangangailangan,” she said.

(Whenever I invite someone to donate, it’s disappointing to hear the answer, “I never thought about it.” People don’t know the extent of the need for blood.) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.