SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

(READ: PART 1: The cost of dying in Duterte’s war on drugs)

PART 2 OF 2

MANILA, Philippines – Representatives of funeral parlors and morgues are a common sight after police operations under President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs.

They are the ones who take care of the slain suspected drug personalities who, if spot reports are to be believed, fought back or “nanlaban“. It is in their utility vehicles where bullet-riddled bodies are boarded to be transported for “processing” amid the chorus of wailing family members.

Since July 2016, at least 3,993 individuals have been killed in anti-illegal drug operations of the Philippine National Police (PNP).

But the suffering does not end with the grief of losing a loved one. It transcends and lingers among families as they are burdened with funeral expenses that are beyond what they can afford.

Investigators’ prerogative

In Quezon City, Rappler found families who were charged between P50,000 ($988)* to P60,000 ($1,186).

Documents obtained by Rappler for 4 of the victims’ families showed a breakdown of the costs issued by Light Funeral Service. “Restoration of human remains” came out to be the most expensive service on the list at P17,500 ($346) while the rest – registration fee, burial permit, 7-day wake duration, casket and hearse, as well as a tarpaulin, some flowers and balloons – totaled about P32,500 ($642).

Rappler has repeatedly sought comment from Light Funeral Service but has received no response as of posting.

But funeral costs shouldn’t be that high in the first place, at least according to two funeral parlor operators based in Malabon and Pasay.

Funeral service for someone who died from “unnatural causes” ranges from only P25,000 ($494) to P30,000 ($593) in Eusebio Funeral Homes in Malabon – almost half of what Light Funeral Service charged the families in Quezon City.

Orly Fernandez, operations manager of Eusebio, says that the possible reason why other funeral parlors charge a lot is their “obligation” to police officers who provide them the bodies.

“Kasi wala akong obligasyon kaya mura iyong serbisyo sa amin,” he told Rappler. “Kasi kung may obligasyon ako sa bawa’t nagbibigay ng bangkay, eh syempre mamahal na iyan.”

(I don’t have any obligation that’s why our services are cheap. If I have an obligation to give to anyone who gives me a body, of course my prices will go up.)

This observation is consistent with what an investigation by human rights watchdog Amnesty International discovered. In its report released in January 2017, Amnesty said that police established dealings with funeral homes, often getting cash for every dead body.

“Police investigators appear to be running a racket with funeral homes, forcing families to spend money they can ill afford to claim the body,” Amnesty said.

Business of picking up the dead

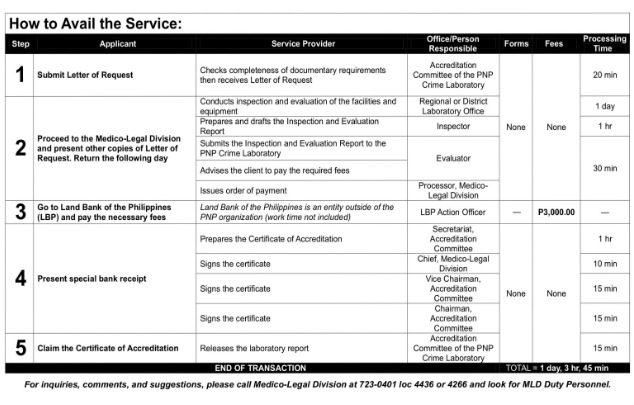

How does one body end up in a specific funeral service? First, a funeral parlor that wishes to accept bodies from police needs to be accredited. Its facilities and equipment are inspected and evaluated to ensure it can accommodate the required services such as autopsy and proper storage. The process, according to a guide by the PNP Crime Lab, takes a little over a day and costs P3,000 ($59).

But being accredited, however, does not guarantee a funeral parlor it will constantly be called to pick up “clients”.

An employee of the PNP Crime Lab, who requested anonymity, said it is usually up to the investigator assigned to one crime incident to choose who the “lucky” morgue will be.

“The police stations, homicide investigators will call funerals that are accredited by the PNP Crime Lab,” he said. “The investigators are the ones who choose who, as long as it is accredited.”

This was echoed by another operator of a Pasay-based funeral service who also requested anonymity. According to him, there are really law enforcers in Metro Manila who prefer those who are “more generous.”At the Supreme Court, where the constitutionality of Duterte’s war on drugs is being questioned, Solicitor General Jose Calida could not answer when asked by Associate Justice Marvic Leonen on November 28 if it was illegal for “police in a precinct to facilitate the funeral arrangement” of those who died during police operations.

Leonen said that these are “what’s coming out in terms of, unfortunately, the drug war.”

Families have long complained about high funeral costs, with most of the victims belonging to lower socioeconomic classes barely having enough to make ends meet. They end up extending the wake period to gather enough donations, borrow from more well-to-do relatives, or suffer through the bureaucracy to avail of government assistance.

This reality is exactly why human rights advocates have dubbed the war on drugs as being a war on the poor. (READ: This is where they do not die)

The fight against high funeral costs has led to familiar scenes of tug-of-wars between relatives with their preferred service provider and funeral services called by police. Still, there are those who have had no choice, especially if they were unable to reach their loved ones’ bodies at the crime scene.

Flor and Michelle, whose relatives were killed in August 2016, spent almost a day looking for the bodies of their relatives in Quezon City. When they finally found them, Light Funeral Service asked them to pay P35,000 ($692) each before they could claim the bodies.

“Kasi sabi nila, nagalaw na raw ng bangkay at na-autopsy na,” Michelle said. “Wala kaming consent tapos na-autopsy na? Kaya tumaas na iyong presyo tapos ayaw na bitawan.” (They told us that the bodies were already processed and had undergone autopsy. We didn’t give our consent. That’s why the price went up and they wouldn’t let go of the bodies.)The two were eventually able to negotiate and lower the “downpayment” to P3,000. But if it was up to them, they would have preferred to go to another funeral parlor, which charged only P25,000.

Move by the government

There have been several moves in the government to protect those who are grieving “against potential abuses by funeral homes.”

House Bill 5036 or the Grievers Protection Act seeks to criminalize and punish the harassment or exploitation of families. These include:

-

Compelling by force, intimidation, deceit, or any other means, a person to undertake the services of a morgue, crematorium or any other death care provider

-

Charging excessive fees for services rendered by those in the death care sector that are well above the “fair value” or average amount charged by those providing the same services in the same city or municipality

-

Failure to provide the nearest kin of the deceased prior written notice of the cost of services

“This is morally reprehensible,” Hontiveros said in a statement. “The victims of the families affected by these ruthless killings are already suffering from shock and trauma, yet they are made to deal with the stress of cobbling together the funds necessary to provide a decent burial for their loved ones.”

Seven months since the issue was brought to light, the Philippine National Police (PNP) has returned to the drug war. While the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency remains to be its lead implementer, human rights organizations fear that the PNP’s return may lead to “more bloodshed and deaths.”Meanwhile, no inquiry has been made into the allegations of abusive funeral homes. – with reports from Rambo Talabong/Rappler.com

*1 USD = P50.7 *Names have been changed to protect their identities

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.